Introduction↑

The role of children in the First World War is a subject which has only recently been considered by international and Italian historiography. Various factors have aroused interest in this topic. Above all, the increasingly frequent categorization of the First World War as a “total war”, both as regards to an intensive mobilization of every type of material and moral energy and in terms of the extensive involvement in war practices of the civilian population, in particular women, occupied peoples, the interned, and refugees. Research about children has also been stimulated by the growing attention paid to the so-called “culture of war”, that is to say the processes of the totalitarian molding of minds during a conflict, in order to consolidate the internal front. In fact, the position of boys and girls in this process appears to have been crucial. This article examines the repercussions of the war on the world of children in terms of their experiences, the use of the image of children for propaganda purposes, and the development of propaganda specifically aimed at minors. The use of child labour in wartime industries and building sites is also considered.

Minors and Their Experience of War↑

The war had a deep impact on families of every social class. According to the 1911 census, there were about 7,700,000 Italian families and just under 6 million men enlisted in the army. Therefore, arbitrarily supposing a uniform mobilization, one can imagine that in statistical terms four-fifths of Italian families had an enlisted man. Where there were minors, they would have witnessed the departure of fathers and brothers, they would, like the rest of the family, have awaited their return home on leave, and they would also have been involved in the tragedies of injuries, mutilations and bereavement. By calculating on the basis of the European average, namely that the widows made up one-third of the wives of the fallen, we can estimate that there were over 200,000 widows in Italy and, once again on the basis of the European average, about 400,000 orphans.[1]

In rural areas, the minors suffered a great deal because of the absence of male adults which, by making women take on the agricultural work and the management of family farms, reduced the time they could give to looking after and bringing up their children. In urban areas and among the working class, it was the increasing employment of women in industrial work which created analogous problems. The soldiers’ letters bear witness, with a wealth of detail, to these situations of hardship which affected the youngest children by considerably lowering their standard of living. The war correspondence also indicates numerous cases of children born in their father’s absence, whom they only came to know during leave or at the end of the war. Compulsory education had to take on new tasks, such as helping and looking after the children of recalled servicemen, as well as promoting the patriotic mobilization of the youngest. Thus, for the first time, caring for children became a national duty and pupils were systematically included in the process of the nationalization of the masses.[2]

Finally, in the regions immediately behind the front, children and adolescents directly experienced the consequences of war actions. They came into contact with troops, were victims of the explosive devices left on the ground by the combatants, were involved in internment, were uprooted by the exodus of civilians after the Austro-German breakthrough in the autumn of 1917, were subjected to ill-treatment by the occupying forces and, because of the latter’s looting, suffered hunger like the rest of the population.[3]

Childhood and Total War↑

Being a total war, involving the masses and materials, but also the mobilization and control of emotions, the First World War could not do without this vehicle of intense emotions and targeted the children and adolescents of both sexes. A war between nations, made up of of economic, intellectual and social energies, combined with the aim of offering resistance and attaining victory, could not ignore that central component of the nation which, by then, the minors had become.

The language of the images vividly evokes this manifold mobilization and this unscrupulous utilization of children in the total war. For example, on the cover of the recreational magazine “Numero”, of 29 July 1917, published in Turin – at a time when there was a lot of talk about the enlistment of the callow youths of the class of 1899 - Italy was presented as a buxom, smiling and gratified woman, feeding a swarming myriad of babies clinging to her swollen breast. Having drunk their mother’s milk, the unweaned infants set out to form a compact group, put on berets and military uniform, shoulder their rifles and in a close-knit group head towards a symbolic frontier which the verses of the caption identify as the “Karst slope”, namely the Karst Plateau, along the Eastern border, where the Italian and Austro-Hungarian armies faced each other. The drawing, by the well-known illustrator Augusto Majani (1867-1959), jokingly alluded to the very young age of the new conscripts, but also symbolized the total investment of demographic energies required by the mass war and intimated military service and war as boys’ fulfilment and necessary destiny.[4]

Another example: a documentary and publicity photograph of the Carminati workshop of Voghera, from 1916/1917, shows a “152 steel grenade”, a tapered and glistening projectile, side by side with a chubby little boy, dressed in white, with long blond curls which made him look like a little angel, his left hand placed on the point of the grenade, almost as if to suggest a comparison with the human body.[5] The humanization of the explosive device and the assimilation of the child with the codes of destruction seem to go pari passu. Also in this case, the screen which should separate childhood from the events of war seems to have completely fallen. Childhood and conflict are not only not incompatible, but they cooperate in a single effort in which the interests of the war industry, national wartime mobilization and delight at the sight of the innocence and angelic beauty of childhood combine harmoniously.

The Image of the Child and the Organization of Consensus↑

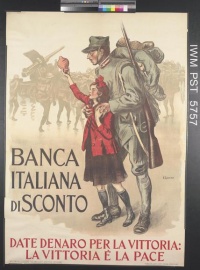

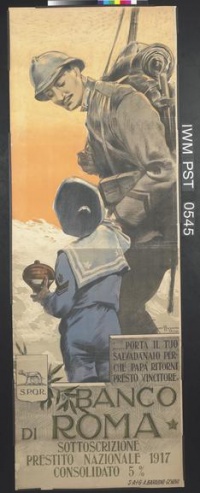

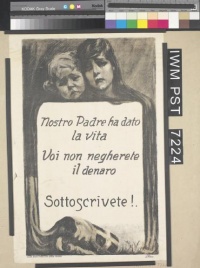

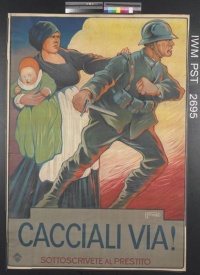

Little boys and girls were a favorite ingredient and recurring theme of the propaganda directed at adults and the whole of society. Defending and protecting them were indicated to be the essential aim of the war. In official public speeches, it was for them, for their present and as a guarantee for their future that the combatants were sacrificing themselves and dying at the front. The threat of a merciless enemy hovered over the children, ready to unleash his predatory sadism on them. The iconography of picture postcards and posters often shows children as victims of Austro-German barbarity. At first, especially in the period of Italian neutrality (July 1914 – May 1915), it was the martyred Belgian children and the French children subjected to occupation, who were used as an argument by interventionist propaganda. Then, after the defeat of Caporetto, it was the turn of the children of the occupied eastern regions. The victimization of the children was an essential part of the construction of the image of the enemy. The tone was often bloodthirsty and cruel: the children are seized by soldiers with a ferocious sneer, exposed to violence, or abandoned to themselves next to mothers who have been raped and killed. The images convey a feeling of compassion and a need for protection which must result in hatred, a desire for revenge, and an urge to offer resistance. Primordial echoes, the evocation of primary defence instincts, and the focus precisely on the most defenseless, namely little boys and girls, serve to create the premises for the acceptance of prolonged sacrifice and bereavement. But side by side with this dramatic tone and the intention of demonizing the enemy, the illustrations of children also used comic tones and caricature, ridiculing the enemy and presenting him as clumsy, deformed and awkward, with the aim of increasing the feeling of security and confidence of success.

In producing figures intended to influence the collective imagination and provide interpretative codes of reality, circulated through picture postcards and posters, the professional illustrators stood out. Some of them were novices, others very experienced in illustrating school books and children's literature.[6] The recurring, central importance of children in this iconography explains the marked presence, among the authors, of specialists in children’s portraits, including many women, often young, for example Vincenzina Castelli, Paola Bologna, Adelina Zandrino, Maria Vinca, and Titina Rota. A typical figure: Adelina Zandrino (1893-1994), Genoese, the daughter of a brilliant Mazzinian journalist, who was a friend of Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863-1938). Her father had done his best to develop her qualities as a painter and encourage her patriotism. In 1915, Adelina Zandrino turned from fashion designs to patriotic picture postcards, many portraying children, as she worked for the publisher Ricordi who produced them in series. The young woman put her talent as a portrayer of delicate and slightly mawkish features, a world filled with babies, at the service of her new cause and passion.

If the subject of the enemy’s brutality inevitably tends towards a representation of war as producing unutterable violence, the dominant role of children in the iconography and imagery often has the opposite effect of favoring the acceptance of war, of making it compatible with human feelings and family surroundings, of, we could say, “taming it”. A case in point is the series of images produced by a man considered one of the most gifted and effective creators of the national imagery of war, Attilio Mussino (1878-1954). The designs present scenes of family life, all characterized by the redefinition of wartime vocabulary within the realms of intimacy and positive feelings. Thus the suffocating gases become the wafted pipe smoke which the soldier father jokingly blows in the face of his little boy, making him step back. The gas mask, always worn by the soldier father evidently home on leave, is also an opportunity to play with the frightened little boy under the serene and smiling gaze of his mother. The “Entente”, namely the military alliance in which Italy participated, becomes the harmony of the usual threesome made up of the soldier father, the mother and the little son. Finally the rations are illustrated with the representation of the father feeding the child.

More generally, putting children on the great stage of the ongoing clash and recurringly using their behavioural and linguistic codes to represent the conflict tended to play down the war, reduce the psychological effects, and reassure, through a sort of infantilization of war. In a certain sense, to use George Mosse's (1918-1999) terminology, this contributed to its “trivialization” - one of the processes which, according to the great historian, favor its acceptance.[7]

The Mobilization of Minors↑

The evocation of the world, codes and icons of childhood in the production of imagery about the war had an impact on children and adults which tended to create a widespread common feeling, at least among the literate sectors of the population, and above all in the urban areas, where the messages conveyed by the means of mass communication arrive with greater frequency.

Little boys and girls were also the intended targets of specific messages of mobilization, of participation in the patriotic war in the ways and with the means which were naturally congenial to them. The main instrument of this specifically directed propaganda was the school. The first three classes of compulsory education numbered over 3 million pupils in 1916, despite the high level of truancy. The educational programs and teaching were progressively adapted to the new climate, making way for ever more frequent references to the ongoing war and the imperatives of patriotism. Children’s periodicals also cooperated in this work. They included, for example, the “Giornalino della domenica”, promoted and supported, from 1906, by the well-known Luigi Bertelli (1858-1920), called “Vamba”, and the “Corriere dei piccoli”, published as a supplement to the “Corriere della sera” starting in 1908.[8] The combined effect of playing down the war and encouraging mobilization was reinforced by the world of toys. Accounts of the time and manufacturers’ catalogues bear witness to the way in which toys tended more and more to resemble the world of the real war, reproducing models of cannons, armored cars, Red Cross ambulances, and making the terminology, instruments and codes of the conflict familiar.

Children were asked to collaborate in the common supportive effort, to encourage family cohesion and therefore the cohesion of the nation. This was seen as the prerequisite of its strength, and hence of victory, which was the only objective to which everyone, both children and adults, had to be committed. Above all, obedience to parents was seen as a metaphor for the greatest social discipline. Moreover, children were asked to make small sacrifices, which were useful for the war effort from a symbolic point of view, but also from a material one. A series of picture postcards by the painter Rosa Menni were very effective in this area. It aimed at exhorting little boys and girls to limit consumption and avoid waste in order to increase the volume of resources intended for the war effort: therefore they should not throw away morsels of bread, not wear out the soles of their shoes skipping, not uselessly smear sheets of paper, nor use cloth for dolls’ dresses which could have more important uses. The bourgeois virtue of frugality and the instructional value of self-control took on a new national significance. The ethics of sacrifice and sense of guilt, which had a big impact on children, aimed at capturing their imagination and involving them in the patriotic mobilization.[9] Something more was proposed for the boys: their preparation to take on the tasks of soldiers through the internalization of the heroic model, which was presented in every way and on every occasion, through school books, newspapers and teachers’ talks. In the children’s literature of the time there is a strong emergence of the subject of little patriotic heroes, which belonged to a tradition exemplified by writers like Edmondo De Amicis (1846-1908) and famous characters like the little Lombard girl who was on lookout duty and the little Sardinian drummer boy.[10]

Naturally, the actual participation of children in the war was a transgression which could be yearned for, but not actually implemented, desired, but not put into practice. Nevertheless, not only in the literature, but in the news reports of the time, there were cases of adolescent boys who had run away from home to join the army, and even of girls who dressed up in male clothing to do the same thing. Furthermore, there was an attempt to directly involve the recently formed scout organizations in auxiliary military tasks, with the aim of consolidating their institutional recognition. In fact, this attempt was discouraged by the political and military authorities. Nevertheless, in the summer of 1916, the founder of the Corpo nazionale dei giovani esploratori italiani (CNGEI), or "National Corps of Young Italian Explorers", managed to get permission for two squads of youths to be involved in surveillance tasks at two railway junctions (Grottaglie al Sud and Porretta in Central Italy).[11]

Girls, who could not hope to one day take up arms, were expected to multiply their efforts in making their contribution to tasks in a way which was doubly substitutionary, inasmuch as they were females and minors and not male adults. Publishers like Bemporad of Florence specialized in producing works aimed at young readers, which focused on the many possibilities of children’s and adolescents’ contributions to the war effort, in a “war without blood” different from that being waged by the combatants, but no less decisive for the final result.[12] In every sense, it can be said that the world of childhood - after the demolition of the barrier which in the 19th century tradition wanted to keep it separate from the adult world and protected from its conflicts - was instead directly addressed and involved in doing its part, as an autonomous social entity, with its own responsibilities in accordance with the principles of total war, which could not overlook any energy nor accept any defection.

Child Labor in Wartime Industries and Building Sites↑

The actual utilization of minors as part of the work force in some sectors concerning the war was important. The standardization of work in the expanding wartime industries favored the massive employment of women and in some cases also minors. In 1918, over 70,000 boys, aged up to sixteen, found work in wartime industries, and there were even more in the small and medium-sized firms concerned with the secondary aspects of armament supply.[13] There were important work opportunities for girls in packaging military uniforms and shoes. Girls aged between eleven and thirteen were involved in the hard work of taking food rations to troops deployed at high altitudes, especially in the villages closest to the front lines, in the wake of traditional feminine work in mountain pastures.[14] There was quite a marked influx of minors behind the front line, involved in logistical work, maintaining the lines of communication and fortifications. A relevant study estimates that about 50,000-60,000 adolescents, aged between twelve and nineteen, were employed in military construction sites behind the front line. Moreover, sample surveys suggest that over 42 percent of the work force in this sector were aged between eleven and nineteen. The majority of these boys naturally came from neighboring areas, such as Veneto and Friuli, but some also came from the South (Puglia, Abruzzi, Calabria and Campania). There were large groups of boys moving through the country, often out of control, driven by the need to earn a salary and sometimes also by a desire for adventure: they were only occasionally stopped and sent away by the surveillance checks at the railway stations.[15]

Conclusion: The Post-War Period↑

The ideological use, both symbolic and practical, of childhood, which had begun on a massive scale during the war, was not abandoned in the post-war period. On the contrary, it continued and in some ways increased, especially through educational and extracurricular activities, like other phenomena linked to the advent of the mass society and politics.

Little boys and girls, in particular school children, were mobilized in the victory celebrations and ceremonies of national mourning, also in this case with the aim of recalling, in the choreographies, the force and the future of the nation. The collective mourning took on a positive significance thanks to the presence, next to the widows and parents of the fallen, of boys who constituted a representation of, and guarantee for, the future, by symbolizing life which continues beyond death. For example, groups of school girls were included in the ceremonies connected with the transfer and burial of the unknown soldier. School children were furthermore given the task of being privileged custodians of remembrance. The boys in particular were assigned to look after plants which, in the so-called Parks of Remembrance, were planted in memory of individual fallen members of the armed forces whose bodies had not been found. Boys and girls were also assigned to look after small altars in classrooms dedicated to fallen heroes.

School children were heavily involved in the construction of the cult of heroes through the use of educational and propaganda techniques already utilized during the war, such as correspondence with the mothers and widows of the fallen. In this area, two cases stand out: that of Ernesta Bittanti (1871-1957), the widow of the irredentist patriot from the Trentino, Cesare Battisti (1875-1916), captured and executed by the Habsburg army, and that of the mother of the Filzi brothers, Istrian irredentist victims of the war and Austrian repression. Both women received many letters from schools throughout Italy in which, under the watchful eye of teachers, the memory of the martyrs was kept alive and patriotic feelings were cultivated by stimulating children’s sensitivity. This use of childhood - with the aim of constructing the myth and the cult of the Great War - and its inclusion in national rituals was later taken up again, intensified and systematized by nascent Fascism, which made it a central component of its ideology.[16]

Antonio Gibelli, University of Genoa

Section Editor: Nicola Labanca

Translator: Noor Giovanni Mazhar

Notes

- ↑ Gibelli, Antonio: La Grande Guerra degli italiani 1915-1918, Milan 1998 (last ed. 2013), p.86.

- ↑ Fava, Andrea: All’origine di nuove immagini dell’infanzia: gli anni della grande Guerra, in Giuntella, Maria Cristina/Nardi, Isabella (eds.), Il bambino nella storia, Naples 1993.

- ↑ Urli, Ivano: Bambini nella Grande Guerra, Udine 2003.

- ↑ Gibelli, Antonio: Il popolo bambino. Infanzia e nazione dalla grande Guerra a Salò, Turin 2005, fig. 1.

- ↑ Ibid., fig. 11.

- ↑ Cesari, Francesca: La nazione figurata (1912-1943). Illustrazioni e illustratori tra letteratura infantile e mobilitazione patriottica, Genoa 2007.

- ↑ Mosse, George L.: Le guerre mondiali. Dalla tragedia al mito dei caduti, Rome-Bari 1990, pp. 139 and ff.

- ↑ Loparco, Fabiana: I bambini e la guerra. Il Corriere dei Piccoli e il primo conflitto mondiale (1915-1918), Florence 2011; Loparco, I bambini e la guerra, Florence 2011.

- ↑ Gibelli, Il popolo bambino 2005, p. 50.

- ↑ Fochesato, Walter: La guerra nei libri per ragazzi, Milan 1996.

- ↑ Pisa, Beatrice: Crescere per la patria. I Giovani Esploratori e le Giovani Esploratrici di Carlo Colombo (1912/1915-1927), Milan 2000, pp. 110-112.

- ↑ Calò, Mario: Guerra senza sangue (Per la nostra indipendenza economica), Florence 1915.

- ↑ Bianchi, Bruna: Crescere in tempo di guerra. Il lavoro e la protesta dei ragazzi in Italia. 1915-1918, Venice 1995, pp. 60-61.

- ↑ Ermacora, Matteo, Cantieri di guerra. Il lavoro dei civili nelle retrovie del fronte italiano (1915-1918), Bologna 2005, p.115.

- ↑ Regarding this whole subject see Ermacora, Cantieri di Guerra 2005.

- ↑ Gibelli, Il popolo bambino 2005, pp. 200-218.

Selected Bibliography

- Bianchi, Bruna: Crescere in tempo di guerra. Il lavoro e la protesta dei ragazzi in Italia, 1915-1918, Venice 1995: Cafoscarina.

- Cesari, Francesca: La nazione figurata (1912-1943). Illustrazioni e illustratori tra lettetura infantile e mobilitazione patriottica, Genoa 2007: Brigati.

- Colin, Mariella / Vagliani, Pompeo: Les enfants de Mussolini. Littérature, livres, lectures d'enfance et de jeunesse sous le fascisme. De la Grande Guerre à la chute du régime, Caen 2010: Presses universitaires de Caen.

- Ermacora, Matteo: Cantieri di guerra. Il lavoro dei civili nelle retrovie del fronte italiano 1915-1918, Bologna 2005: Il Mulino.

- Faeti, Antonio: Guardare le figure. Gli illustratori italiani dei libri per l'infanzia, Turin 1972: Einaudi.

- Fava, Andrea: All’origine di nuove immagini dell’infanzia. Gli anni della Grande Guerra, in: Giuntella, Maria Cristina / Nardi, Isabella (eds.): Il bambino nella storia, Naples 1993: Edizioni scientifiche italiane.

- Fochesato, Walter: La guerra nei libri per ragazzi, Milan 1996: Mondadori.

- Gibelli, Antonio: Il popolo bambino. Infanzia e nazione dalla Grande Guerra a Salò, Turin 2005: Einaudi.

- Urli, Ivano: Bambini nella Grande Guerra, Udine 2003: Gaspari.