The Battle of Gorizia↑

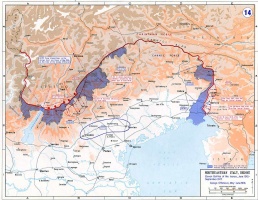

At the outbreak of the Great War, the 25th division stationed at Cagliari, commanded by Luigi Capello (1859-1941), was assigned to the Third Army. It took part in the battles on the Carso until such time as Capello, having been promoted Lieutenant General on 28 September 1915, was entrusted with the command of the Sixth Army corps facing Gorizia and the heights of Podgora and of Sabotino. Despite the numerous attacks unleashed during the third and fourth offensives on the Isonzo, the Austrian counteroffensive of January 1916 thwarted the best efforts of the Italians. The development of the artillery and better preparations led to the staging of a spectacular action on 9 August to storm the Gorizia bridgehead, which was held by Capello, even though the provision of sufficient reinforcements would have led to a genuine breakthrough by the Austrians. It was nonetheless the first Italian victory of any substance, and one that caused Capello’s star to shine brightly. The general was subsequently the subject of much envy, in part because of the cordial relations he had maintained with Leonida Bissolati (1857-1920), with whose reformist socialism he had long sympathised.

Bainsizza and Caporetto↑

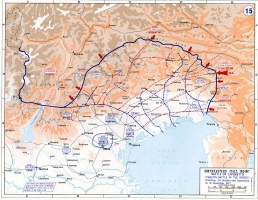

Luigi Cadorna (1850-1928) viewed Capello as a serious rival and, on 7 September 1916, transferred him to the command of the 23rd Army Corps. Admittedly, relations improved subsequently, and Capello, after his command of the 5th Corps of the First Army, was recalled to the Isonzo front, where he was entrusted with the command of the Gorizia zone. It was from the Gorizia zone that he organised the tenth battle of the Isonzo for the control of the heights around Venezia Giulia. Despite being able to call upon superior forces, and despite careful planning, Capello only won tactical, not decisive successes, for which the costs were high. Nonetheless, they enabled him, having assumed command of the Second Army on 1 June 1917, to gain an important victory on the Bainsizza plateau which, although not decisive, served to confirm that the only successes achieved by the Italian army bore Capello’s signature. In view of a planned autumn offensive and with the aim of pre-empting the anticipated enemy attack, Capello prepared, against Cadorna’s advice, a major counteroffensive, which was conducted in the teeth of opposition from the High Command and despite lacking adequate resources. Communications had been compromised by a deterioration in the health of Capello, who in October fell ill with nephritis and had therefore to leave the front for several days. When the general again rejoined the high command on 23 October, it was with difficulty that he repelled the attack unleashed by the Austrians, who broke through at Caporetto, driving back the far left of the Second Army. After a consultation with Cadorna, General Capello argued for ordering the general retreat on to the Tagliamento, in order to allow his troops to draw breath, but sickness forced him once again to relinquish his command, this time to General Luca Montuori (1859-1952). Appointed on 26 November to the command of the Fifth Army, constituted from what remained of the Second Army and from disbanded men who had returned to the ranks, Capello distinguished himself by organising a modern propaganda network and establishing a good relationship with the troops. On 8 February 1918 he was relieved of his post, put at the disposal of the Commission of Enquiry into the causes of Caporetto and, despite having mounted a vigorous and detailed defence, the decision was taken on 3 September 1919 to retire him. Capello’s critical attitude to the General Staff and the army high commands led him at first to manifest some sympathy for fascism, although after the laws passed in the aftermath of Giacomo Matteotti’s (1885-1924) murder he became firmly opposed.

Andrea Argenio, Università degli studi Roma Tre

Section Editor: Marco Mondini

Translator: Martin Thom

Selected Bibliography

- Ascolano, Dario: Luigi Capello. Biografia militare e politica, Ravenna 1999: Longo.

- Beccherle, Maurizio: Luigi Capello, un 'anti-Cadorna' mancato, in: Isnenghi, Mario (ed.): Gli italiani in guerra. Conflitti, identita, memorie dal Risorgimento ai nostri giorni. La grande guerra. Dall’Intervento alla 'vittoria mutilata', volume 3, number 1, Turin 2008: UTET, pp. 493-499.

- Capello, Luigi: Caporetto, perché? La 2a armata e gli avvenimenti dell'ottobre 1917, Turin 1967: Einaudi.

- Mangone, Angelo: Luigi Capello. Da Gorizia alla Bainsizza, da Caporetto al carcere, Milan 1994: Mursia.

- Mola, Aldo Alessandro (ed.): Luigi Capello. Un militare nella storia d'Italia. Atti del convegno di Cuneo, 3-4 aprile 1987, Cuneo 1987: L'Arciere.

- Rochat, Giorgio: Capello, Luigi, in: Ghisalberti, Alberto M. (ed.): Dizionario biografico degli italiani. Canella-Cappello, volume 18, Rome 1975: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, pp. 497-502.