Site of Neutrality, Site of War↑

The Netherlands' borders were the most important site of war experience for the Dutch. The international law of neutrality regulated at the second Hague Peace Conference of 1907 required that neutral countries protect their territorial integrity from neutrality violations. As the Netherlands bordered two belligerent states – Germany in the east and Belgium in the south – it mobilised its armies early, on 30 July 1914. It primarily aimed to guard its borders, but also to protect the country from any invasions. Fortunately for the Dutch, these did not come.

Both sets of warring powers were keenly interested in the movement of people, information and goods across the Dutch borders. As a direct result of the pressure placed on them by the Entente governments to curb smuggling and guarantee the integrity of the Netherlands' Overseas Trust import guarantees, the Dutch armed forces enforced a strict military surveillance of people and goods moving across the border and into the border regions. In August 1914, its High Command had already imposed a “stage of siege” along much of the borderline, ensuring military control over most civic administration. By 1917, military authority was in place in 70 percent of all Dutch communities. They were declared to be either in a “state of siege” or the less pervasive “state of war.” The main reason for doing so was to control the movement of goods and attempt to curb the extraordinary amounts of smuggling.

Occupation↑

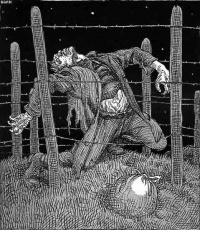

For the Central Powers, especially Germany, the primary threat posed by the Dutch border was the movement of people and information from occupied Belgium via the Netherlands to the Entente. As a result, Germany placed a considerable amount of pressure on the Dutch government to prevent espionage and the movement of volunteers for the Belgian army across its territory. The German concern about the use of the Dutch border zone was so great that in April 1915, it took the drastic step of building a lethal electrified fence from Vaals, in Dutch Limburg, to the place where the Schelde River crossed the Dutch borderline. The fence ran for 300 kilometres. It is estimated that as many as 3,000 people lost their lives to the fence.

Complicating the lives of border guards and locals even more was the arrival of hundreds of thousands foreigners. These included foreign civilians residing in enemy territory, Belgian and French refugees fleeing battlefronts and soldiers who either purposely or accidentally crossed the Dutch border. During the German siege of Antwerp in October 1914, almost 1 million Belgians escaped to the Netherlands. This created a humanitarian crisis of unparalleled proportions, stretching the country's resources to the maximum. The situation was further complicated by the fact that more than 30,000 Belgian soldiers also entered the Netherlands at the same time. By international law, all foreign soldiers arriving in neutral territory had to be interned in camps and placed under military guard for the duration of the war. Nearly 47,000 foreign soldiers, most of them Belgian, were interned in the country during the war. The Netherlands also had to deal with large numbers of escaped prisoners of war, mainly from Germany, and as of 1918, thousands of deserters from the German armies.

All this activity made the Dutch border region a highly contested zone between the belligerent and neutral governments, but also for local residents. Whereas before the war, locals barely recognised that there was a border line – some towns had even grown across the border – during the war they were not only aware of the border but also of the armed authorities that maintained it on both sides. The border was a dangerous place to live, and the lives of borderlanders were fundamentally affected by their war experiences.

Maartje Abbenhuis, University of Auckland

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Selected Bibliography

- Abbenhuis, Maartje: Where war met peace. The borders of the neutral Netherlands with Belgium and Germany in the First World War, 1914-1918, in: Journal of Borderlands Studies 22/1, 2007, pp. 53-77.

- Abbenhuis, Maartje: The art of staying neutral. The Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918, Amsterdam 2006: Amsterdam University Press.

- De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: De Groote Oorlog. Het koninkrijk België tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (The Great War. The kingdom of Belgium during the First World War), Amsterdam 1997: Atlas.

- Roodt, Evelyn de: Oorlogsgasten. Vluchtelingen en krijgsgevangenen in Nederland tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (War guests. Refugees and prisoners of war in the Netherlands during the First World War), Zaltbommel 2000: Europese Bibliotheek.

- Wolf, Susanne: Guarded neutrality. Diplomacy and internment in the Netherlands during the First World War, History of Warfare, Leiden 2013: Brill.