Formation of the Black Hand (Unification or Death)↑

The Black Hand (Unification or Death) was formed by a ring of influential officers of the Serbian army, headed by Dragutin Dimitrijević (1876-1917), known as “Apis”, in May 1911.[1] The immediate context for this formation was Austria-Hungary’s 1908 annexation of Ottoman Bosnia-Herzegovina, a move that thwarted the ambitions of Serbian nationalists who had themselves hoped to annex the province in whole or in part to an enlarged Serbian state. But the leading members of this new association had been more or less active in Serbian politics and public life since staging a palace coup in Belgrade in 1903 (usually referred to in Serbian as the “May Coup”).[2] “Unification” indicated “Serbian” lands outside of Serbia that were to be redeemed through incorporation with the homeland: the Christian-populated lands in the Ottoman Balkans (today’s Macedonia and Kosovo), and, of course, Bosnia-Herzegovina itself. The founders of Unification or Death took their inspiration from the German and Italian nationalist movements that had been instrumental in the great national integrations of the late 19th century (the group’s journal for example, was called Piedmont). But Unification or Death was Janus-faced: looking outwards towards Serbian irredenta but also, ominously, looking inwards towards the leaders of the state. Apis and his men did not rule out political, cultural, military or terrorist means to achieve their goals, either at home or abroad.

The Balkan Wars and the Civil-Military Dispute of 1913-1914↑

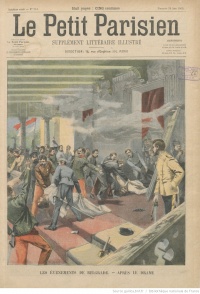

When Serbia, along with the Balkan alliance of Montenegro, Greece and Bulgaria attacked the Ottoman Empire in autumn 1912, members of the Black Hand took part in the general military mobilization for war and fought in both the first and second Balkan wars. The aftermath of the war victories saw an acrimonious dispute between the ruling government of Nikola Pašić (1845-1926) and the leaders of the Black Hand (who had joined forces with the parliamentary opposition to Pašić), involving the question of whether the newly won territories should be under military or civilian control. This dispute spoke to the long-term tensions between the leaders of the Black Hand and civilian politicians dating back to the May Coup. In the wake of the Balkan wars, civilian politicians and the crown wanted to consolidate the gains of 1912-1913 and replenish the country’s exhausted military and economic forces. But Black Hand members were ready to strike out again should the opportunity arise. With the Ottomans all but expelled from the Balkans, the most coveted remaining irredenta now lay in Habsburg Bosnia.

Sarajevo↑

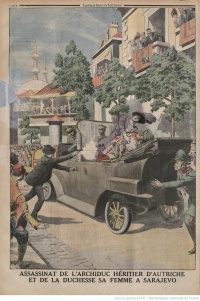

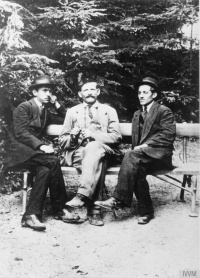

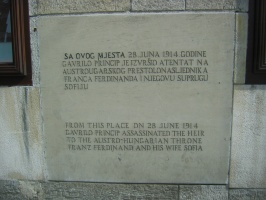

The febrile post-victory atmosphere in 1913-1914 was not restricted to Serbia itself. The élan of the Serbian army, its successes in full-scale military mobilization, and its military prowess on the battlefield seemed to speak to the vigour of this national state against the entropy of its imperial opponents. This was certainly the lesson taken by the revolutionary wing of the South Slav nationalist youth movement, comprising young men of various nationalities throughout Austria-Hungary’s South Slav provinces, most of whom were enrolled as first-generation students in the monarchy’s gymnasia and universities.[3] Members of these groups were responsible for a spate of unsuccessful assassination attempts on Habsburg officials during 1913-1914 that alerted the Black Hand to an opportunity to facilitate violence against the monarchy. After meetings in Belgrade between leading Black Handers and members of the revolutionary South Slav youth, arrangements were made for a cell of Bosnian youths to be armed and to cross the border between Serbia and Bosnia for the purpose of assassinating Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914) while he was on a state visit to the province in June 1914. The Serbian government and crown, whom Vienna held responsible for the killing, are not seriously implicated in this attack (although they may have had some prior knowledge of it): it was masterminded by the Black Hand.

War and the Salonica Trial↑

As in 1912 and 1913, Black Handers fought for Serbia in the First World War, often serving on the frontline. Many Black Handers were killed in the fierce battles against the Central Powers from 1914-1916. The consequent weakening of the Black Hand gave the civilian leaders an opportunity to – if not entirely eliminate – then at least marginalize the Black Hand, and especially Apis, who remained a powerful and dangerous opponent. The civil-military conflict that had smouldered before 1914 had not been resolved with the outbreak of the war, despite Serbian propaganda about the unity of a nation in arms against the enemy.[4] In 1917, the Serbian wartime government of Nikola Pašić set aside its differences with Aleksandar Karadjordjević, Prince of Serbia (1888-1934) - to whom the ailing Peter I. Karadjordjević (1844-1921), Aleksandar’s father, had passed the royal prerogative in 1914 - and in the summer of 1917, at the front in Salonica, they staged a rigged trial in which Apis and other leaders of the Black Hand were falsely accused of planning Aleksandar’s assassination. Three Black Hand ringleaders, including Apis himself, were executed in July 1917 – other leading Black Handers were imprisoned, and fifty-nine officers believed to be associated with the organisation were pensioned off. Rumours abounded that the leaders of Serbia were sacrificing Apis, the guiding hand of the Sarajevo assassination, prior to peace talks with Austria-Hungary. But the so-called Salonica Trail was in reality the dénouement of a long struggle for supremacy between Serbia’s civil and military leaders. Apis – conspirator, spymaster, regicide, and demiurge of Serbia’s golden age – had finally been outmanoeuvred.

Legacy↑

The Black Hand, although no longer an effective force after the war, continued to vex Yugoslavia’s civilian leaders. In the interwar Kingdom of Yugoslavia, discussion of the Salonica Trial was a virtual taboo. The trial was eventually reopened and overturned by the regime of Josip Broz (1892-1980), known as "Tito", in the 1950s: the communists extolled Apis’ implacable opposition to the "bourgeois" Serbian government and to Aleksandar’s "monarcho-fascism".[5] Apis’ reputation, like that of his protégé in political assassination, Gavrilo Princip (1894-1918), has been revisited and reassessed many times over the past century. The Black Hand has inspired novels, memoirs, plays, movies and so on. Its role in the Sarajevo assassination and the full details of the Salonika Trial will likely never be uncovered. But it can be said with confidence that the Black Hand played a pivotal role in Serbian history at a time when Serbia was pivotal to the history of the First World War.

John Paul Newman, National University of Ireland Maynooth

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Notes

- ↑ I am grateful to Dr. Dmitar Tasić for his comments on an earlier draft of this entry.

- ↑ On the coup, see Vucinich, Wayne: Serbia between East and West. The Events of 1903-1908, Stanford 1954 and the work by Serbian author Vasić, Dragiša: Devetstotreća, Majskiprevrat. Prilozi za istoriju Srbije 8. Jula 1900 do 17 Januara 1907 [Nineteen Hundred and Three, The May Revolution. Contributions to the History of Serbia from 8 July 1900 to 17 January 1907], Belgrade 1925.

- ↑ On the Sarajevo assassination and its roots, see Dedijer, Vladimir: The Road to Sarajevo, New York 1966 and Gross, Mirjana: Nacionalne ideje studentske omladine u Hrvatskojuoci I svjetskog rata [The National Ideas of the Student Youth in Croatia on the Eve of the World War], in: Historijskizbornik 21–22 (1968–1969), pp. 75-143.

- ↑ Cornwall, Mark: Austria-Hungary and ‘Yugoslavia’ in: Horne, John (ed.): A Companion to the First World War, Oxford 2010, pp. 369-85.

- ↑ See Mackenzie, David: The Exoneration of the ‘Black Hand’. 1917-1953, New York 1998.

Selected Bibliography

- Dedijer, Vladimir: The road to Sarajevo, New York 1966: Simon and Schuster.

- MacKenzie, David: Apis, the congenial conspirator. The life of Colonel Dragutin T. Dimitrijević, Boulder; New York 1989: Columbia University Press.

- MacKenzie, David: The 'Black Hand' on trial. Salonika, 1917, Boulder; New York 1995: Columbia University Press.

- Newman, John Paul: Yugoslavia in the shadow of war. Veterans and the limits of state building, 1903-1945, Cambridge 2015: Cambridge University Press.