Introduction↑

When America entered the war on 6 April 1917, some men refused to take up arms. There were cases of conscientious objectors and draft dodgers (known as slackers) throughout the country, but these were the minority. Most doughboys (the popular nickname for American troops), inspired by assumptions and preconceived notions about war (emerging in part from Civil War memorialization), acknowledged Germany as the enemy and felt it was their duty to fight. While many young men volunteered, the draft supplied around 72 percent of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). Once inducted, compliance and patriotism were paramount among the new soldiers. Overall, they believed in the war and hated the enemy. Still, self-coercion existed – some men did not want to suffer humiliation or endure ostracism from fellow soldiers or friends and family. The strong use of war propaganda augmented the doughboys’ will to fight. This article examines these issues below in five sections: compliance with conscription; conscientious objection; soldiers; political education of soldiers; mutiny and disobedience within the army; and negotiation and discipline within the army.

Compliance with Conscription↑

By 30 June 1917, 160,084 men enlisted for duty at 401 United States recruiting stations. The army rejected 206,059 applicants due to physical reasons, illiteracy, age or because they were not yet American citizens.[1] Foreign-born men were anxious to serve. Enthusiasm was especially evident with Poles. 40 percent of the first 100,000 volunteers were Polish, at a time when Poles represented four percent of the United States population.[2] Among the German-born, however, enthusiasm for service lay with the Fatherland, as nearly 500,000 men returned to Germany to join the war effort there. Earlier that month, on 5 June, 9,660,000 men ages twenty-one to thirty registered for the draft. Of these, approximately 800,000 registrants received deferments based on essential civilian employment vital to the war effort.[3] Overall, National Registration Day was peaceful. As many men responded to conscription, Civil War images filled their minds. Thoughts of heroism and glory in battle spurred them forward as they recalled family stories or literature from their youth. Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) and his Rough Rider exploits during the 1898 Spanish-American War were also alive and well, which made combat appear to be dangerous and exciting. When the draft arrived, most men accepted their call as one of duty.

In a national lottery on 20 July, the first selection of draft registries took place, and 687,000 men entered the army. Foreign draftees accounted for 487,434; of these, 200,000 were not yet American citizens who waived their exemptions in order to serve in the AEF.[4] Due to the war, the government streamlined the naturalization process, allowing 280,000 immigrants to become citizens and serve in the military. By the end of the war, 24 million men registered for the draft, furnishing 72 percent of the military. Around 43 percent of all registrants received exemptions from military service because they were married and provided the only income for their families. The federal government granted this exemption to relieve the additional economic burden of providing support for soldiers’ dependents. The majority of draftees served willingly, but some opposed the service.

Defiance with Conscription↑

3 million men (about 11 percent of draft-age males) either refused to register, or when called to report for duty at their induction center, decided not to appear. Americans termed a man who shirked his call to service a slacker. Mainstream and official publications portrayed slackers as not only unpatriotic and unfit citizens, but also as cowards. Women often acted as a catalyst that pushed some shirkers into the service. Groups of young women, such as those in Watertown, Massachusetts, stood at entrances to manufacturing companies and presented draft dodgers with white feathers, the customary emblem of cowardice.[5] Other women refused to marry men who evaded service.

Some men who refused registration joined groups opposed to the draft, such as socialist organizations, or the American Union Against Militarism, which protested conscription. Others even attempted, to no avail, to challenge Selective Service in the courts. The Supreme Court upheld conscription as constitutional in January 1918, with Chief Justice Edward D. White (1845-1921) stating in Arver v. United States that: “the very conception of a just government as its duty to the citizen includes the reciprocal obligation of the citizen to render military service in case of need, and the right to compel it.”[6] Almost one-third of the nation’s draft evasion took place in the rural South. There, poverty and illiteracy along with lack of documented identification forms allowed large numbers of migrant workers to slip through the Selective Service registration process.

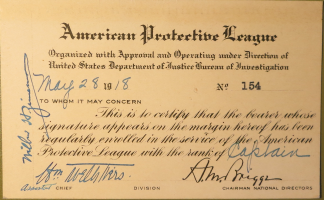

The American Protective League (APL), organized by Chicago businessmen, offered to assist the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation to ensure compliance with conscription laws in its efforts to round up slackers. This group, active in cities, sought out shirkers in cooperation with local and federal authorities, and became a force of coercion for military service. The Justice Department began a tighter campaign in March 1918 aimed at tracking down evaders. The first “slacker raid” took place in Pittsburgh, and federal agents, local police, and APL members conducted citywide sweeps to locate unregistered draft-eligible men. When the APL disbanded in February 1919, it boasted nearly 250,000 members, which included some women.

Conscientious Objection↑

The most prevalent form of anti-conscription activism was conscientious objection. These draftees who refused to fight claimed exemption based on their personal or religious pacifist views. At first conscientious objection as an official category was limited to members of long-standing religious faiths that prohibited participation in war. In 1918, however, Secretary of War, Newton D. Baker (1871-1937), decided to extend the objector classification to include those who rejected combat on a personal level. During the war, about 64,693 men claimed conscientious objector status.[7] When these men arrived at their training camps, fellow soldiers and officers pressed them to change their minds. Most, about 80 percent, decided to enter combat, such as future Medal of Honor recipient Alvin C. York (1887-1964). A native Tennessean, at first, York declared himself as a conscientious objector on religious grounds. After discussions with his commanding officer and intense reflection, York concluded he could participate in combat.

No matter what the reason behind the objection, religious or personal, the army expected all conscientious objectors to serve in alternate noncombat roles. Most of the objectors accepted assignments as farm workers or ambulance drivers. Many American citizens could not understand why some men refused to serve on grounds of conscience. Former President Theodore Roosevelt dismissed the conscientious objectors as “slackers, pure and simple, or else traitorous pro-Germans.”[8] Some men refused combat based on their political beliefs, such as socialists who refused to fight for a capitalist country – a prominent example was Rhodes Scholar and philosophy professor Carl Haessler (1888-1972).

Religious Opposition↑

Most conscientious objectors sought relief from military service on religious grounds. Groups such as the Mennonites and Hutterites had long histories of refusing to bear arms, but the government insisted on scrutinizing each objector and his motives. Mainstream organized religious groups, such as Catholics, Jews and Protestants did not support conscientious objectors within their groups. Most citizens regarded these objectors as slackers attempting to hide behind religion. The German-speaking Mennonite communities of the Midwest withstood the most harassment regarding objector status. Other sects, such as Russellites or Jehovah’s Witnesses also received scorn. In April 1918, for example, a mob in Walnut Ridge, Arkansas, whipped, tarred and feathered five Russellites and ordered them to leave town.[9]

Discipline of Conscientious Objectors↑

From May 1917 until November 1918, the army handled 64,693 claims for exemption based on conscience. Local draft boards accepted 56,830 of these claims, most of which recognized religious objections to combat. The army forcibly inducted or sent to trial men who refused to serve due to political or humanitarian viewpoints. The army declared almost every objector guilty at trial and sent these men to military jails such as Alcatraz in California or Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. Overall, the army imprisoned nearly 500 conscientious objectors. Within two years of the Armistice, the army released all of these prisoners.[10] Some prisoners died in jail due to illness and others committed suicide. Treatment at these prisons was generally harsh and depended on the sentiments of the commanding officers. Major General J. Franklin Bell (1856-1919) at Camp Upton, New York, treated objectors without animosity. At Fort Riley, Kansas, guards humiliated, neglected and even abused prisoners under the command of General Leonard Wood (1860-1927).[11] During the war, the army court-martialed 540 conscientious objectors. Seventeen received the death penalty, although the army executed none; 142 men faced life in prison. The average sentence handed down to an objector was sixteen and a half years in prison.[12]

Howard W. Moore↑

The case of Howard W. Moore (1889-1993) illustrates an example of harsh discipline. Moore declared himself a non-religious conscientious objector in a formal deposition to his draft board on 28 December 1917. When Moore refused to comply with his 22 January 1918 draft notice, the army sentenced him to five years in prison. While incarcerated at Fort Douglas, near Salt Lake City, Utah, guards deprived Moore of food and water. Suffering under deplorable conditions, Moore claimed in his autobiography that when General John J. Pershing (1860-1948), AEF commander, inspected Fort Douglas, he focused on the prisoners and remarked: “These men are dirt beneath my feet.”[13] Later when imprisoned at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Moore’s guards placed him in solitary confinement due to his refusal to work, and shackled him to the cell bars for nine hours a day. Released one day before Thanksgiving in 1920, Moore lost ninety pounds and developed tuberculosis while imprisoned.

Discipline of Religious Sects↑

The army usually accepted claims for exemption based on religious grounds, except in cases of conscientious objectors who practiced unconventional religions. Members of the Mennonite and Hutterite sects suffered twofold: they were German or of German descent and they were conscientious objectors. Since Canada granted conscientious objector status to practitioners of religions prohibiting war, some Mennonites and Hutterites avoided the draft by immigrating to Canada. Those that remained in America suffered severe penalties. For example, the army sentenced forty-five Mennonites from Oklahoma to twenty-five years in prison for their refusal to wear an army uniform. The army rejected noncombatant options by Hutterites because they believed such tasks as driving ambulances still contributed to the war effort. When South Dakotan Hutterite brothers Michael Hofer (1893-1918), David Hofer (1890-1958) and Joseph Hofer (1894-1918), and fellow Hutterite Jacob Wipf (1887-1970) arrived at Camp Lewis on 28 May 1918, their refusal to sign military papers resulted in their arrest. Their court-martial began on 10 June, and five days later, the army sentenced the Hofers and Wipf to twenty years of hard labor at Alcatraz. While there, they refused to don army uniforms, so prison guards threw them into solitary confinement dressed only in their underwear. The Hofers and Wipf endured beatings and starvation at Alcatraz until the army transferred them to Fort Leavenworth after the Armistice. There, the punishment continued. Joseph, twenty-four years old and Michael, twenty-five, developed pneumonia and died in the prison infirmary in late November 1918. The army released David Hofer on 2 January 1919 and Wipf on 13 April 1919.

Political Education of Soldiers↑

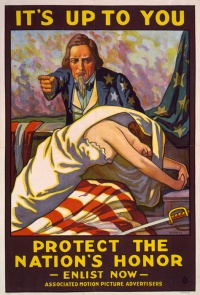

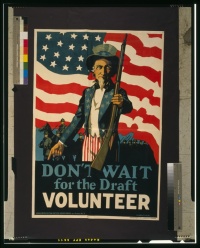

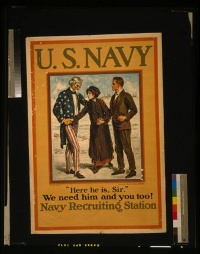

The American government used instructive programs and propaganda to galvanize public acceptance of the war effort, as well as persuade slackers and conscientious objectors to alter their opinions. With an aggressive campaign waged in society and the army, the government convinced many men the war was just.

Political Education within Society↑

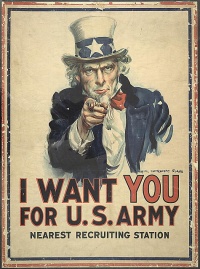

One week after America declared war, President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) established the Committee on Public Information (CPI) in order to secure public aid, encourage enlistment and convince those already in the armed forces that American participation in the war was warranted. Appointed as head of the CPI, George Creel (1876-1953) masterfully used mass media to encourage citizens to enlist in military service, purchase war bonds and practice conservation. Comparing Germans to barbarians by the use of the term “Huns,” publishing stories of German atrocities, and predicting doom if Germany triumphed, were ways Creel and his committee influenced Americans to support the war effort. The CPI also made excellent use of posters, newsreels, speakers (e.g. the Four Minute Men), magazine advertisements and newspaper articles. Creel’s committee printed 20 million pro-war posters, more than every other warring nation combined. The CIP printed 5 million copies of the most famous American poster, which featured Uncle Sam stating: “I Want You,” by James Montgomery Flagg (1877-1960).

Political Education within the Army↑

Secretary of War Baker instructed his War Department to mail each prospective soldier a pamphlet entitled, Home Reading Course for Citizen-Soldiers. It explained that the United States was at war for liberty, not for power or more territory. Other lessons in the pamphlet centered on skills needed for military living conditions, and the heroics of soldiers from the American Revolution and the Civil War. Baker appointed Raymond B. Fosdick (1883-1972) to head the Commission on Training Camp Activates (CTCA), which received support from groups such as the Young Mens Christian Association (YMCA) and American Library Association. The CTCA was responsible for developing sports programs, recreation facilities, religious services, movie screenings, libraries and numerous other services for troop enjoyment. The CTCA designed these programs and activities to boost morale, and more importantly, to discourage degrading behavior, insubordination and the frequenting of saloons and brothels. In May 1918, the War Plans Division created the Morale Division, which worked to solidify America’s war goals in the minds of soldiers. Both the CTCA and the Morale Division worked extensively in stateside training camps. Overseas, the soldiers’ newspaper, the Stars and Stripes, published weekly beginning in February 1918, boosted morale. The YMCA organized recreation and entertainment for the AEF abroad.[14]

Mutiny and Disobedience within the Army↑

Inappropriate military behavior did exist within the training camps, but it occurred more often while men waited for embarkation. Soldiers often went Absent Without Official Leave (AWOL), especially if close to New York City, where the allure of the metropolis proved too potent. Enlisted men expressed bitterness toward martial hierarchy and authority. They were not accustomed to the subordination to rank present in the military. Doughboys often rankled against what they perceived as lost individualism.[15]

Officers, often with little training, provoked soldiers into questioning authority. The greatest instances of rebellion arose on the Western Front. Military Police (MPs) followed troops on the offensive in order to urge stragglers forward. Some soldiers attempted to blend in with the wounded in order to avoid combat. MPs, well aware of this trick, would search groups of wounded to detect deserters and a number of troops even wounded themselves to avoid combat. Hospital personnel labeled self-mutilation patients and placed them in special wards for further investigation. Deserters often grouped together along the edge of the front where they stole food from French villages and tried to avoid the MPs. During the Meuse-Argonne offensive in autumn 1918, MPs arrested fifteen to twenty deserters a week. Although General Pershing ordered officers to shoot deserters, this only happened on rare occasions. During the war, the MPs were still in the development stage. As the war progressed, the number of MPs grew from 150 for every division of 20,000 or .07 percent of the AEF, to three times that percentage by spring 1919.[16] The army viewed the increase as a positive growth factor rather than a reaction to desertions.

Negotiation and Discipline within the Army↑

Even though officers did not shoot deserters on sight, the AEF still enforced draconian measures when they deemed it necessary. Army discipline was strong because commanders needed unwavering obedience in order to achieve victory. Punishments for deserters and stragglers included court-martials, humiliation and hard labor. These tactics eased as the months passed and officers realized that many new doughboys found it difficult to adapt to military hierarchy and authority. Over time, the army developed an understanding that the commanders retained strict authority, but troops could negotiate obedience to lesser offenses, such as when to salute superiors. Another example of relaxed regulations occurred when stateside soldiers in training camps went AWOL to visit their families, especially during holidays. These absent soldiers would return to camp within ten days in order to avoid a charge of desertion. When these men returned to camp, the company officers assigned them an extra duty day instead of a tougher punishment. The army concluded that providing troops with leave boosted morale and limited AWOL occurrences. A soldier’s outlook was vital to the AEF. The compromises made by the army strengthened training and indoctrination, which, in turn, enabled doughboys to make the right choice, particularly when tempted to desert.[17]

Even though the AEF maintained high morale, infractions still occurred. Misdemeanors represented most crimes and the army found few soldiers guilty of serious offenses. General Pershing confirmed death sentences and judged forty-four criminal cases that carried the death penalty. The army executed thirty-three men with murder or rape. Between 6 April 1917 and 30 November 1918 there were 4,316 cases of soldiers going AWOL in both America and Europe. For the crime of desertion, from 6 April 1917 until 31 December 1918, the army charged 5,584 troops and 2,657 of these men received convictions. The army sentenced twenty-four convicted deserters to death, but executed none. AEF desertion levels marked a historic low during the war. In 1917, the percentage of desertions was at its lowest point since 1909. The following year, desertions went to their lowest since 1830.[18]

Conclusion↑

Why did doughboys fight? In the midst of combat, most men did not reflect on Wilson’s claims to “make the world safe for democracy” or to wage “a war to end all wars.” The men of the AEF fought for their own survival and the lives of their fellow soldiers. They fought for duty, patriotism and manhood. Some resisted, but the majority of men, enlisted or conscripted, followed orders through a combination of coercion and consent. In the end, consent mattered more. As volunteer ambulance driver John Dos Passos remarked: “We had spent our boyhood in the afterglow of the peaceful nineteenth century…What was war like? We wanted to see with our own eyes. We flocked into the volunteer services. I respected the conscientious objectors, and occasionally felt I should take that course myself, but hell, I wanted to see the show.”[19]

Edward A. Gutiérrez, University of Hartford

Section Editor: Edward G. Lengel

Notes

- ↑ Mead, Gary: The Doughboys. America and the First World War, Woodstock 2000, pp. 450.

- ↑ Laskin, David: The Long Way Home: An American Journey from Ellis Island to the Great War, New York 2010, pp. 128.

- ↑ Mead, Doughboys, p. 70.

- ↑ Sterba, Christopher M.: Good Americans: Italian and Jewish Immigrants during the First World War, New York 2003, p. 57.

- ↑ Capozzola, Christopher: Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen, Oxford 2008, p. 31.

- ↑ Arver v. United States, 245 U.S. 366 (1918).

- ↑ Mead, Doughboys, p. 363.

- ↑ Coffman, Edward M.: The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I, Lexington 1998, p. 74.

- ↑ Capozzola, Uncle Sam Wants You, p. 63.

- ↑ Zieger, Robert H.: America’s Great War: World War I and the American Experience, Lanham 2000, pp. 62.

- ↑ Zieger, America’s Great War, p. 62.

- ↑ Mead, Doughboys, p. 363.

- ↑ Moore, Howard W.: Plowing My Own Furrow, New York 1985, p. 151.

- ↑ Keene, Jennifer D.: Doughboys, the Great War, and the Remaking of America, Baltimore 2001, pp. 76-78.

- ↑ Kennedy, David M.: Over Here: The First World War and American Society, Oxford 2004, p. 210.

- ↑ Meigs, Mark: Optimism at Armageddon: Voices of American Participants in World War One, New York 1997, pp. 232.

- ↑ Keene, Doughboys, pp. 68-70.

- ↑ Mead, Doughboys, pp. 207.

- ↑ Dos Passos, John: One Man’s Initiation. 1917, Ithaca 1969, pp. 4-5.

Selected Bibliography

- Axelrod, Alan: Selling the Great War. The making of American propaganda, New York 2009: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brewer, Susan A.: Why America fights. Patriotism and war propaganda from the Philippines to Iraq, Oxford et al. 2011: Oxford University Press.

- Capozzola, Christopher Joseph Nicodemus: Uncle Sam wants you. World War I and the making of the modern American citizen, Oxford; New York 2008: Oxford University Press.

- Coffman, Edward M.: The war to end all wars. The American military experience in World War I, Lexington 1998: University Press of Kentucky.

- Creel, George: How we advertised America. The first telling of the amazing story of the Committee on Public Information that carried the gospel of Americanism to every corner of the globe, New York; London 1920: Harper & Brothers.

- Gutièrrez, Edward A.: Doughboys on the Great War. How American soldiers viewed their military experience, Lawrence 2014: University Press of Kansas.

- Keene, Jennifer D.: Doughboys, the Great War, and the remaking of America, Baltimore 2001: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Kennedy, David M.: Over here. The First World War and American society, New York 1980: Oxford University Press.

- Kingsbury, Celia Malone: For home and country. World War I propaganda on the home front, Lincoln 2010: University of Nebraska Press.

- Laskin, David: The long way home. An American journey from Ellis Island to the Great War, New York 2010: Harper.

- Lengel, Edward G.: To conquer hell. The Meuse-Argonne, 1918. The epic battle that ended the First World War, New York 2009: Henry Holt and Co.

- Mead, Gary: The Doughboys. America and the First World War, New York 2000: Overlook Press.

- Meigs, Mark: Optimism at Armageddon. Voices of American participants in the First World War, New York 1997: New York University Press.

- Sterba, Christopher M.: Good Americans. Italian and Jewish immigrants during the First World War, Oxford 2003: Oxford University Press.

- Stoltzfus, Duane C. S.: Pacifists in chains. The persecution of Hutterites during the Great War, Baltimore 2014: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Zieger, Robert H.: America's Great War. World War I and the American experience, Lanham 2000: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.