Introduction↑

The memory of the Great War is so encrusted with mythology that it is not easy to uncover the attitudes of New Zealand soldiers at the time. There are three useful sources: Firstly, the observed behavior, which this allows the historian to deduce attitudes from action. Secondly, the writings: many New Zealand soldiers wrote diaries; more wrote letters back home, usually to immediate family and especially their mothers. They have the virtue that they were written immediately after events and record changing attitudes. There are biases towards the letters of the fallen, whose letters were kept because they were sacred to family; and towards middle-class people whose sons were more literate. Letters were censored by officers, and self-censored by soldiers fearful of upsetting their mothers. But they remain a major source.

Other writings include three collections issued during the war – the Anzac Book[1] contributed by Gallipoli soldiers and New Zealand at the Front from 1917 and 1918. There were few novels written by returned soldiers - John A. Lee’s (1891-1982) 1937 autobiographical novel Civilian into soldier is a notable exception - and only half a dozen memoirs, including Cecil Malthus’ (1890-1976) classic about Gallipoli,[2] published by veterans immediately after the war. Many diaries and letters have been published by families in the 1990s and 2000s. Apart from Ormond Burton’s (1893-1974) The Silent Division (1935) semi-official histories from the 1920s were authored by ex-officers whose views did not necessarily reflect those of ordinary soldiers.

Another important source are oral histories. The woman journalist Robin Hyde (1906-1939) interviewed James Stark, a wild hero of no man’s land, for a brilliant book, Passport to Hell (1935) but not until the 1980s was serious oral history research carried out with veterans. Then, in 1988, Maurice Shadbolt (1932-2004) published Voices of Gallipoli, while Jane Tolerton and Nicholas Boyack recorded 250 hours of interviews with eighty-four veterans. There were also some radio and television recordings. By this time, the men were in their nineties and their memories had been reshaped by subsequent events.

Uniformity of attitude↑

These sources allow us to generalise about attitudes. Although individual views were affected by class, ethnic and religious background, and particular war experiences, there is a remarkable uniformity in response among New Zealand soldiers. This essay begins with the expectations of men upon enlisting. We explore their encounter with the battlefield. This transforms their general attitude to war. We examine their judgements about the enemy, and their allies, which raises a final question about their understanding of national identity as a result of war experience.

Initial Response to War↑

In the fifteen years before the First World War New Zealand men learned that being good at war was central to their identity. National pride at the achievements of the New Zealand troopers in the South African War and of New Zealand rugby players on the All Black tour of Britain in 1905-1906 suggested that men trained on the New Zealand frontier could compensate the Empire for the urban degeneration of British men. At school, men had learnt about the military heroes of the Empire and from 1909 compulsory military training was introduced for males between twelve and twenty-one. Most New Zealand men believed that war service was a national duty and a glorious enterprise.

Initial enthusiasm↑

Within four days of war’s outbreak, 14,000 men volunteered, and there were stories of men abandoning farm work to walk or ride to recruiting offices. One man rejected for varicose veins had an operation and changed his name to re-enlist.[3] In all, 91,941 men volunteered for service – 38 percent of the eligible men. This may not seem high, and volunteering did not prevent New Zealand introducing conscription from August 1916. This produced another 30,000, even though men of eligible age included those married with children, men in their late thirties and early forties in busy careers, the sick and the disabled. Few male New Zealanders in their twenties, unmarried and physically fit, did not serve.

If men voted with their feet, they also wrote of their enthusiasm. Many used the phrase, “the great adventure”, when explaining their enlistment.[4] They saw war as an exciting way to see the world. Once the expeditionary force (or “main body”) arrived in Egypt, they became restive for battle. On 25 January 1915, William Malone (1859-1915) recorded, “The Turks are advancing. As the news spread the camp rang with cheers. Everybody is in very good humour.”[5]

Confronting the Conditions of War: Boredom↑

Most soldiers found some aspects of war testing such as the lack of privacy and the monotony – “same work/same menu/same dugout/same riflefire/same early rising/same late retiring...”, diaried Frank Cooper.[6] Most yearned to be back with their families. There were also torments particular to different conflicts. New Zealand soldiers fought in three theatres: Gallipoli, the Middle East and the western front.

Gallipoli↑

Between 25 April and 20 December 1915 about 14,000 New Zealanders landed on the Gallipoli peninsula and, apart from a short spell at Cape Helles, they survived on a cramped area about a kilometre wide overlooked by the Turks uphill. It was impossible, even when bathing in the sea, to escape bullets or shrapnel. Casualties were high – over 2,700 men were killed, and some 4,800 wounded. With no man’s land littered with uncovered bodies and the place crawling with flies, sickness (especially dysentery), was rife. The smell could be sensed ten miles out to sea. During summer it was exhaustingly hot; in November came snow. The hard biscuits and bully beef were indigestible, and the saltiness created raging thirsts poorly salved by the daily quart of water. The fighting was intense and at times, such as the August offensive, the already sick men were asked to undertake demanding tasks in exposed situations.

Middle East↑

Three of the four mounted regiments at Gallipoli rejoined their horses in early 1916 and set out over the next two and a half years to push the Ottoman forces back across the Sinai Peninsula and Palestine. This was a mobile front, and the men had the companionship of their mounts, but conditions were difficult – extremes of heat during the day (up to 50°C) and of cold at night. Thirst and monotonous food were constant issues, and there were some vicious skirmishes and several major battles – over 500 New Zealanders lost their lives.

Western Front↑

When Leonard Hart (1894-1973) arrived at the western front his immediate response was, “Give me the mud before the flies and disease of Gallipoli... .” Others noted that in France there were spells away from the front line when you could recover equilibrium. But as Hart continued, this did not make the place “in any way desirable”.[7] In Flanders, where the water table was high, the Germans held the higher ground and the weather, especially in 1917, was consistently wet; conditions were atrocious – shell holes of water, gooey mud that brought on trench feet, lice in the clothes, rats fossicking for scraps. Food remained a source of complaint and there was much marching with packs weighing up to 86 lbs. The military stalemate was depressing, and advances of only 1,000 metres cost many lives. Almost 12,000 New Zealanders died on the western front. Their experience reached a nadir at Passchendaele in October 1917 when, in heavy rain, exhausted troops came up against uncut wire and German pillboxes, and suffered from their own artillery shells falling short: 846 men died in two hours.

New Attitudes to War↑

Horrors of war↑

How did these experiences affect soldiers’ attitudes? Most often they produced a growing bitterness that expectations about glorious war had been so misplaced. This started early. Within two months of landing at Gallipoli, Charles McConchie (1893-1971) wrote home, “Anyone who has never been on the field of battle cannot in the least realise what it is like... It is, plain speaking, awful. In fact, it is like being in the depths of Hell itself.”[8] Ten days earlier George Bollinger (1890-1917) wrote: “The world outside has great confidence in their men but I often wonder if they realise or try to realise what a hell the firing line is and know that every man desires and cannot help desiring immediate peace.”[9]

Men reaching the western front echoed such views. After the Somme in September 1916 George Cain (1895-1976) remembered, “I wished the earth would open up and swallow me – anything to get away from the horrors which were so much worse than anything I could have imagined.”[10] The same month Norman Gray (1891-1936) wrote home, “All are sobered, and you no longer hear talk of what the Anzacs will do.”[11] By 1917 a deep melancholy had descended on the men. Many were keen to get an injury, a “Blighty” – “a ticket to England and hospital, clean sheets and tender care”.[12] What is striking, especially in New Zealand at the front, was the contrast of glorious expectation with muddy reality. A mock field postcard offers words to be deleted: “I am covered with Glory/dirt/decorations/mud/medals/manure/parasites.”[13]

Resistance↑

How did the men cope with this disillusion? A few inflicted wounds on themselves to get to Blighty; others collapsed psychologically; a few went AWOL; one soldier deserted to the Germans. There was little organised resistance – no mass mutiny, and, although the Etaples Base Uprising of September 1917 was started by New Zealanders, it quickly became a widespread revolt.[14] The few riots came after the war when the men were anxious to get home. More often New Zealand men coped by retreating into a stoic acceptance of their situation.

Attitudes to Officers↑

The soldiers expressed bitterness by moaning about their officers. Ernest C. Clifton (1893-1975) is typical. After landing at Gallipoli, he complains “the more we do, the more they want done. We are simply working out somebody’s promotion”. After the evacuation he is furious that the officers received a special Christmas dinner presented on a gilt menu, while the men had porridge and biscuits without jam. On New Year’s Day he seethes: “This ‘officers only’ is a bugbear, and is a scandalous business.”[15] In writings from the western front too there was plenty of animosity towards the privileges of officers. New Zealand soldiers were particularly vehement towards Imperial officers and there was discussion, and obvious pride, about their refusal at times to salute Imperial officers.

Mateship↑

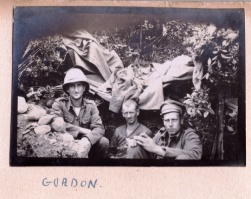

Another strategy of survival was a close relationship with mates. Sometimes, because the forces were organised geographically, mates were friends of long acquaintance or even brothers. At Gallipoli, Gordon Harper (1885-1916) and his brother Robin Harper (1887-1972) each carried a dog whistle to summon the other when needed; and they searched out their school friends. More often, mates were simply thrown together by war and became dependent on each other. At Gallipoli George Tuck (1884-1981) wrote, “Hard swearing, hard living, rough men. Yet, when their comrades are wounded, and in need of assistance, nothing is too great trouble. They give everything and everything they have.”[16] From the western front Wilfred Smith (1885-1917) tells his wife how his “good pal old Fred Honore” shared money, gave a hand when they got “beat” on a march, and worked together digging trenches. Each carried the other through the tough times.[17] Cecil Malthus concluded that comradeship was “the finest thing war has to offer”.[18]

Drinking, Gambling and Sex↑

Mateship also offered good times away from the lines. On Gallipoli, there was no such relief apart from controlled spells on Lemnos, but in France there were periods to enjoy a few drinks at estaminets. Soldiers remembered such occasions fondly. Murray Morriss (1897-1992) recalled, “When we were out of the line, we always had a darn good booze up when we come out because if you didn’t you’d have gone mad.”[19] Drink was used to repress traumas even in the lines. John Russell (1891-1977) remembered that after a bombing raid he “couldn’t get any sleep without first making myself more or less sizzled with rum in order to drown the memory of those blood curdling yells for which we had been responsible”.[20]

Another escape was gambling. Norman Gray recalled that on returning to camp near Cairo in early 1916, 100 to 150 Gallipoli veterans gathered each night in the desert to play Crown and Anchor.[21] In France, soldiers reported that the popular diversion was the huge schools organised by the “two-up kings” (“two up” was a distinctive Australasian gambling game).[22]

The final escape was sex. Letters to mothers reveal little about soldiers’ attitudes on this subject. But their behaviour suggest the attractions of prostitutes in Cairo or Paris were considerable. In the first six months of 1917 the official VD rate for all troops in England was 34 per 1,000. For the New Zealanders it was 134.[23] In oral histories and especially in John A. Lee’s Civilian into soldier, the acceptance of sex as relief from the horrors of war was explicit. One veteran recalled, “Everybody was out to have a good time because you didn’t know if the next minute you were going to be killed.”[24] Sex, drink, gambling, and good times with the mates were accepted as healthy escapes from the horror of the trench.

Attitudes to the Enemy↑

Ottomans↑

Although the New Zealanders sailed off to fight the Germans, the first “enemy” they met were Ottoman forces (Arabs and Turks although usually described as Turks). Their attitude towards them was coloured by their general racism towards non-British peoples. On arrival at Suez the Main Body was told: “The natives in Egypt have nothing in common with Maoris. They belong to races lower in the human scale, and cannot be treated in the same manner. The slightest familiarity with them will breed contempt.”[25]

So initially there was racist contempt for the Gallipoli enemy. But the presence of German officers provided an alternative focus of dislike and attitudes to the Turks softened. The armistice on 24 May offered an opportunity to observe the enemy. William Malone commented, “I saw a German officer. I hated him at first sight. His manner was most offensive.” But the Turks “seemed cheery and friendly enough”.[26] As the campaign proceeded there was greater respect. Walter Carruthers (1894-1918) was typical: “The Turks have played the game here as well as anybody could have played it and we have got a lot of time for them as fighters and men.” Interviews with veterans years later confirmed this viewpoint. They remembered “Johnny Turk” or “Jacko” as clean fair, fighters.[27]

Germans↑

Prejudices against Germans were harder to overcome. New Zealanders had gone to war following public trumpettings about the invasion of Belgium. It coloured their viewpoint. Wilfred Smith told his wife to remind his kids “what brutes the Germans are, and how they have killed women and little children”.[28] The soldiers expressed special vitriol about the military rulers of Germany. In 1916, Norman Gray wished he had “Kaiser Bill” at one end of a stretcher carrying “a 500 lb. block of iron crosses through his own barrage fire for sixty hours on end, with Hindenburg at the other end”.[29] But the more the soldiers realized that ordinary German soldiers too were sharing the burdens of trench life, they showed sympathy. They were appreciative when the Germans did not fire on the wounded and “played the game” (a common phrase).[30] “Old Fritz” was not “any better or worse than our soldiers”.[31]

Attitudes towards Allies↑

Attitudes towards the allies also changed. Later in the war there were derogatory comments about the French for being dirty, and several soldiers warned their families not to “give another farthing to anything connected with these rotten Belgians”.[32] But the main focus of comparison was on the New Zealanders’ Australian and British colleagues.

Australians↑

Initially most New Zealand soldiers thought of themselves as “better Britons”, stronger, less class-ridden, with the qualities of natural English gentlemen. They distinguished themselves from the Australians whom they regarded as uncouth larrikins. In Cairo, William Malone dismissed the Aussies as “a loose beery lot”, while the New Zealanders looked “like soldiers”.[33] Claude Pocock (1887-1978) described the Australian as “a skiting bumptious fool”.[34] Once the ANZACs landed on Gallipoli opinions changed fast. The New Zealanders spoke of their admiration for the Australians’ bravery, even if it sometimes extended to recklessness. Bert Honnor (1894-1916) wrote home in September 1915, “By Jove, the feeling between our boys & the Australians is marvellous.”[35] The Aussies were accepted as good mates.

English↑

Views of the English changed equally fast. Some of the British regulars in Cairo seemed impressive and they were generally regarded positively, but Herbert Kitchener’s (1850-1916) new recruits were scathingly dismissed. As early as December 1914, George Bollinger (1890-1917) dismissed them “as a lot of half-grown boys”.[36] At Gallipoli, Cecil Malthus recalled “much petty shabby thieving” amongst the Tommies, while the Australians respected “our” code of “no stealing among ourselves, only from army stores or from officers!”[37] After the August offensive animosity rose. The British soldiers were blamed for dawdling at the Suvla landings and for losing the heights of Chunuk Bair. Bert Honnor wrote home: “There is no love lost between colonial & Tommy. When I say Tommy I don’t say the regular Tommies. I mean this pet lot of Kitchener’s.”[38] Two weeks later he describes them as “damn curs & cowards & that is praising them”.[39]

Judgements did not improve on the western front. The criticisms were the same – that the “Tommies were diminutive men of poor physique”;[40] that their NCOs were brutal; and that their officers with monocles and “haw! haw! style of voice” were derided and refused salutes.[41] Some made an exception for the Scots whom they considered more like colonials, solid and less class-ridden.

Most New Zealand soldiers spent time training or in hospital or on leave in Britain. There was much they found attractive. They write of their excitement at seeing “olde England” – the England of thatched cottages and quaint villages. They enjoy visiting legendary places such as Westminster Abbey. They are welcomed and fed by relatives. But criticisms quickly surface – the levels of poverty, English food and the weather. They think the place too snobbish and ruled by convention and are unimpressed by British political leaders. Peter Howden (1885-1917) wrote his wife, “Most of the new arrivals are wondering what sort of a country this is that we are going to fight for. The general opinion is that we should hand it over to the Germans and apologize to them for having nothing better to give them.”[42]

Growing Nationalism↑

In comparing themselves with the soldiers and peoples of other countries New Zealand soldiers developed a stronger sense of their own identity. As they observed the performance of their own men in battle and received the plaudits of Imperial leaders, a national pride emerged. Within weeks of the Gallipoli landing William Malone wrote, “I hope I shall be able to tell the people of New Zealand what grand fellows their soldier men are. Nothing better in the world... the Tommies have christened my men the “White Gurkhas”. We are very proud of the sobriquet and mean to live up to it.”[43] Ormond Burton described how a nationalism grew deeper and stronger as the men “marched from one ordeal of terror to another”.[44] The sense was expressed in the development of the distinctive lemon-squeezer hat, and the adoption of the terms “digger” and “Kiwi” to describe themselves. When Peter Howden joined them in France, he wrote to his wife, “By jove Girlie it is a thing to be proud of being a New Zealander I can tell you, when you realise and see and know how our chaps behave over here.”[45]

Aspects of this nationalism are worth noting. First, the national pride extended to an appreciation for the performance of the Maori, especially at Gallipoli. Second, although there was a pride in the soldiers, it did not necessarily extend to the nation’s leaders. Many diarists were scathing about the visit to the troops on the western front by the prime minister, William Massey (1856-1925), and his deputy Joseph Ward (1856-1930) in July 1918. Alec Hutton (1890-?) was “thoroughly disgusted”, claiming that Massey was “immensely unpopular here”.[46] Third, despite the hostility towards the British, and the English in particular, the soldiers’ nationalism was not an independent anti-imperial nationalism. There was no evidence that the soldiers returned from the experience wanting a republican New Zealand to sever its imperial connections. Rather the pride was that New Zealand boys had served the Empire superbly and had shown the British if not the Aussies that they were the Empire’s finest sons.

Conclusion↑

The attitude of New Zealand soldiers to the Great War was never constant. Diaries and letters show that their initial enthusiasm was radically transformed by the experience of the trenches. Later oral histories suggest that veterans’ understandings of the war continued to evolve in later years as memories were reshaped by popular opinion and public mythology.

Jock Phillips, Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Section Editor: Kate Hunter

Notes

- ↑ The Anzac Book written and illustrated in Gallipoli by the men of Anzac, London 1916.

- ↑ Malthus, Cecil: Anzac. A retrospect, Christchurch 1965.

- ↑ Taylor, William: The Twilight Hour. A personal account of World War I, Morrinsville 1978, p. 16; but see Hucker, Graham: The Great Wave of enthusiasm : New Zealand Reactions to the First World War in August 1914 – A Reassessment, New Zealand Journal of History, 43/1 (2009), pp. 59-75.

- ↑ E.g. Stanfield, Sydney, in: Tolerton, Jane: An Awfully Big Adventure, Auckland 2013, p. 11; Norman Gray, who begins his war diary, “The great adventure has begun…”, in: Phillips, Jock / Boyack, Nicholas / Malone, E.P. (eds): The Great Adventure. New Zealand soldiers describe the First World War, Wellington 1988, p. 72.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 28.

- ↑ Quoted in Boyack, Nicholas: Behind the lines. The lives of New Zealand soldiers in the First World War, Wellington 1989, p. 48.

- ↑ Leonard Hart, letter 1 January 1918, in: Phillips, Great Adventure 1988, p. 139.

- ↑ Charles William McConchie to his father, 19 June 1915, in: Harper, Glyn: Letters from Gallipoli. New Zealand soldiers write home, Auckland 2011, p. 92.

- ↑ George Bollinger diary, 9 June 1915, in Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

- ↑ Cain, George: Packsaddle to Rolls-Royce, Penrose 1976 p. 82.

- ↑ Norman Gray, letter 24 September 1916, in: Phillips, Great Adventure 1988, p. 94.

- ↑ Cain, Packsaddle to Rolls-Royce 1976, p. 62.

- ↑ New Zealand at the Front, 1917, https://archive.org/details/newzealandatfron00lond (Retrieved 28 April 2015), p. 38.

- ↑ Mutiny at Etaples Base in 1917, Past and Present, number 69, pp. 88-102; Allison, William / John Fairley: The Monocled Mutineer, London 1978.

- ↑ Clifton, E.C., diary 9 May 1915; 26 December 1915; 1 January 1916, in Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

- ↑ George Tuck, letter of 19 May 1915, in: Harper, Letters from Gallipoli 2011, p. 140.

- ↑ Phillips, Great Adventure 1988, p. 221.

- ↑ Malthus, Anzac 1965, p. 16.

- ↑ Tolerton, An Awfully Big Adventure 2013, p. 178.

- ↑ Quoted in Boyack, Behind the Lines 1989, p. 106.

- ↑ Phillips, Great Adventure 1988, p. 80.

- ↑ Burton, O.E.: The Silent Division: New Zealanders at the front 1914-19, Sydney 1935, p. 190.

- ↑ See Tolerton, Jane: Ettie, a life of Ettie Rout, Auckland, 1992, p. 150.

- ↑ Tolerton, An Awfully Big Adventure 2013, p. 222.

- ↑ Quoted in Pugsley, Chris: Gallipoli: The New Zealand Story, Auckland 1984, p. 75.

- ↑ Phillips, Great Adventure 1988, p. 54.

- ↑ E.g. Tolerton, An Awfully Big Adventure 2013, pp. 71, 259.

- ↑ Phillips, Great Adventure 1988, p. 218.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 96.

- ↑ E.g. Tolerton, An Awfully Big Adventure 2013, p. 141; Phillips, Great Adventure 1988, p. 150.

- ↑ Boyack, Behind the Lines 1989, p. 92.

- ↑ Phillips, Great Adventure 1988, p. 176.

- ↑ Ibid. p. 25.

- ↑ Quoted in Pugsley, Christopher: The Anzac experience: New Zealand, Australia and Empire in the First World War, Auckland 2004, p. 21.

- ↑ Bert Honnor, letter of 9 September 1915, in: Harper, Letters from Gallipoli 2011, p. 179.

- ↑ George Bollinger, diary 19 December 1914, in Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington.

- ↑ Malthus, Anzac 1965, p. 100.

- ↑ Bert Honnor, letter of 26 August 1915, in: Harper, Letters from Gallipoli 2011, p. 175.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 178.

- ↑ Miller, Eric: Camps, Tramps and Trenches: the diary of a New Zealand sapper, Dunedin 1939, p. 84.

- ↑ Quoted in Boyack, Behind the Lines 1989, p. 194.

- ↑ Phillips, Great Adventure 1988, p. 169.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 47.

- ↑ Burton, Silent Division 1935, p. 46.

- ↑ Phillips, Great Adventure 1988, p. 185.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 242.

Selected Bibliography

- Boyack, Nicholas: Behind the lines. The lives of New Zealand soldiers in the First World War, Wellington; Winchester 1989: Allen & Unwin; Port Nicholson Press.

- Burton, O. E.: The silent division. New Zealanders at the front, 1914-1919, Sydney 1935: Angus & Robertson.

- Harper, Glyn (ed.): Letters from Gallipoli. New Zealand soldiers write home, Auckland 2011: Auckland University Press.

- New Zealand / British Expeditionary Force, New Zealand Contingent: New Zealand at the Front. Written and illustrated by men of the New Zealand Division, London 1917: Cassell & Co.

- Phillips, Jock / Boyack, Nicholas / Malone, E. P. (eds.): The great adventure. New Zealand soldiers describe the First World War, Wellington; Winchester 1988: Allen & Unwin; Port Nicholson Press.

- Phillips, Jock: A man's country? The image of the Pakeha male. A history, Auckland 1996: Penguin Books.

- Tolerton, Jane: An awfully big adventure. New Zealand's World War One veterans tell their stories, Auckland 2013: Penguin.