Introduction↑

In his 1978 history of British soldiers in the First World War, Denis Winter noted: “It is surprisingly difficult today to form an estimate of the way soldiers regarded the war as a whole.” Winter blamed a combination of the “nonsense” written by non-combatant authors and the focus on “the everyday detail or the concrete experience in combatant memoirs.” Soldiers, he concluded, “at the time spoke little and later wrote little on what they thought either of the war or about their role in the war.”[1]

In fact, as the work of historians such as Richard Holmes (1946-2011), Lyn Macdonald and Peter Liddle have since demonstrated,[2] soldiers of the Great War did, indeed, write and speak about their role in the war and their attitude towards it. In fact, so extensively have British soldiers recorded their war experiences, and had their observations recorded for them by interested historians and descendants, that the challenge facing social and cultural historians of the conflict is to capture the sheer range of experiences and attitudes in their analyses. Approaches to this conundrum have included focusing on specific units,[3] and the use of cultural categories, such as class and gender, as theoretical frameworks for the exploration of soldier subjectivities.[4]

This article will examine the responses of a very small number of British servicemen to aspects of their war experience, including motivations for enlistment, reactions to the methods employed by the military to instil military discipline and sustain morale, and the impact of varying contingencies such as weather, access to food and bathing water, and sector of service. It will conclude by assessing the impact of the post-war culture of disillusionment on how we now remember soldiers’ opinions of the conflict and how this has, in turn, shaped cultural memory of the conflict itself. Throughout it will be argued that attitudes towards the war not only ranged across a wide spectrum, from enthusiasm to disillusionment, but that individual perspectives were contingent upon a range of factors across time, making any attempt to summarise attitudes towards the war among five million servicemen an impossible task.

Mobilisation and Enlistment↑

As Adrian Gregory noted, “Simplistic generalisations about war enthusiasm not only iron out the complexities of society; they also gloss over the complexities of individual response.”[5] From the start of the war, men’s attitudes were notable for their variety. The poet, Julian Henry Francis Grenfell (1888-1915), already an officer of four years’ standing when war broke out, famously wrote in 1914, “I adore war. It is like a picnic without the objectlessness of a picnic.”[6] Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (1886-1967) would later echo this imagery in his fictionalised memoir, Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1928), in his description of George Sherston’s experience of the first month of the war: “For me, so far, the War had been a mounted infantry picnic in perfect weather.”[7] Sassoon, in the figure of Sherston, was, however, more ambivalent about the war than Grenfell, even at this early stage. Having “slipped into the Downfield troop by enlisting two days before the declaration of war,” he “felt safe in the Army, and that was all I cared about.”[8] As Sassoon’s biographer, Jean Moorcroft Wilson, argued:

While such an attitude might be categorised as enthusiasm for, or at least an appreciation of, war, it was an enthusiasm defined by highly personal concerns.

Such self-interest can also be seen in the approach to enlistment of less well-known servicemen. David Randle McMaster viewed the outbreak of war as an opportunity for social self-improvement, writing to his parents, “I am quite willing to do my share in the defence of the country and I am quite certain that I could serve … + possibly as a commissioned officer as they are giving commissions free to qualified persons.”[10] For John Townshend, enlisting was a way of helping his family financially: “He wrote to his mother [upon enlisting] and said that there will now be no food or clothes to buy for him and he will send them money.”[11] Given that one of the most immediate impacts of the outbreak of war was mass unemployment, such responses among working-class volunteers were unsurprising.

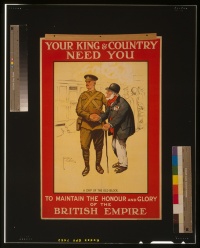

In letters home from training and the front, many men articulated more idealistic reasons for enlisting. Foremost among these was the desire to keep their homes and families safe. “I hope you will not mind me telling you that I volunteered so as to help protect you,” George R. Barlow wrote to the aunt who had raised him. Cyril Seton Rawlins (1893-1971) similarly told his mother that “It is a great & glorious thing to be going to fight for England in her hour of desperate need”, and to “remember I am going to fight for you, to keep you safe.”[12] Such comments reflect the idealism which saw large numbers of men join up in the first few weeks of August 1914.

However, if soldiers’ motivations for fighting varied as to reason, from self-interest to chivalric loyalty to abstract idealism, they also varied across time. This can not only be seen in the decline in voluntary enlistments from the autumn of 1914, which ultimately resulted in the passing of the Military Service Acts and the introduction of conscription in 1916; it is also evident across shorter time periods. Rates of enlistment were highly variable even within the first few weeks of the war, which have tended to be characterised as witnessing a “rush to the colours.” In fact, significant spikes in enlistment appear to have been coincident with publications of the Mons Despatch in The Times on 25 August 1914 and the clarification of the system of separation allowances at about the same time.

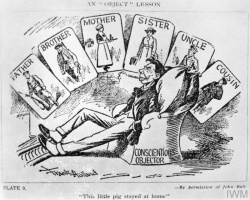

Similar considerations would continue to shape men’s willingness to serve throughout the war, as reflected in the variations in attitude echoed in the work of the regional Military Service Tribunals from 1916.[14]

Discipline and Morale↑

Given the variations in attitude among enlisting servicemen, including the increasingly evident reluctance of men to serve voluntarily at the expense of their families, it is worth considering the methods employed by the military authorities to mobilise and enforce men’s willingness to engage actively in the war effort. These included both carrot and stick approaches, both of which served to shape men’s attitudes towards the war as a whole.

The stick of discipline is probably remembered more distinctively than the carrot of morale building in the aftermath of war, particularly that of capital punishment, used against 346 men of the British armed forces. These, as Helen McCartney pointed out, “formed only 11.23 percent of all men sentenced to death by courts martial, and 0.006 percent of the British army as a whole.”[15] Certainly, awareness of the punishment was high at the time, with sentences read out to all units, reflecting commanders’ views that the death penalty formed a necessary form of deterrence. Even if the majority of servicemen never directly witnessed or encountered an execution, consciousness of its use as a form of discipline was considerable, with many expressing if not disgust then certainly discomfort with the practice. Dominion troops could be particularly vocal in their condemnation of British practices that they witnessed. When a man serving with the 5th Canadian Field Ambulance was required to attend the execution of a man by firing squad, it was not willingly; the unit biographer wrote:

There does, however, appear to have been an acceptance that some crimes, particularly that of deliberately letting comrades down in the face of danger, deserved harsh punishment. As Frederic Manning (1882-1935) wrote in his semi-autobiographical novel, Her Privates We:

Individual attitudes towards capital punishment as a form of deterrence can thus be seen to be highly ambivalent. Less ambivalent appear to have been attitudes towards field punishments, sanctions which, along with detention, fines, deductions from pay, confinement to barracks, punishment drill, extra guard duty and admonition, made up the repertoire of military punishments. Field Punishment Number One, which involved tying the prisoner to a wheel or fixed object for two hours a day in three out of any four consecutive days, up to a total of twenty-one days,[18] was viewed with particular disgust by many of the civilians-turned-soldiers who made up the majority of the British army in the First World War. This reflects the fact “that harsh punitive sanctions, deemed essential in controlling the regular army, never achieved the same importance among the Territorials” or the New Army volunteers and conscripts. This was not to suggest that these men did not believe in discipline as a central element of life in the armed forces, simply that “civilian … code[s] of honour and self-respect compensated for a lack of formal military discipline and inspired more inventive, unofficial sanctions.”[19] Additionally, the use of fatigues and demotions to the ranks for infractions such as malingering or drunkenness appear to have been accepted with equanimity, viewed as equivalent to punishments meted out for similar behaviour in civil life.

Men’s attitudes towards morale-building was similarly influenced by their civilian identities, with Territorial units in particular preferring “to motivate their men through positive, civilian-inspired strategies, rather than enforcing behaviour through threat of punishment.”[20] Such strategies were evident from initial training, which was designed to build unit cohesion as the basis of military morale,[21] and ranged from the building of fictive kinship within the unit through officers’ day-to-day care for their men to the organisation of sports days and theatrical events while on rest. Officers were keenly aware of the importance of maintaining morale through the provision of baths and food as often as possible, with many arranging with their families for unit parcels to be provided on a regular basis, paid for by their private income. Charles Reginald Chenevix Trench (1888-1918), for example, would write with suggestions of foodstuffs for his wife, Clare Cecily Chenevix Trench, née Howard (1892-1989), to include in packages, such as the dry kippers which “If successful we could get … for the men regularly.”[22] Unsurprisingly, men who experienced the war as part of a unit which received extensive and coherent training, or with a paternalistic officer who fostered strong unit cohesion through non-military activities, tended to express a more positive attitude about their war experience than those who did not.

Personal Experience↑

Attitudes toward the war were not only contingent upon unit of service and the quality of individual officers in supporting unit cohesion. They were also dependent on a range of factors which not only were beyond the control of military authorities, but which also changed, often dramatically, over time. Poor weather, particularly cold and wet weather on the Western Front and sandstorms in Egypt, made men less sanguine about the war. Similarly, lack of bathing facilities (and the consequent infestation of lice), disruption to the mails (leading to lack of contact with home), and disruption to the food supply all led to the perennial activity of the soldier, grousing, as did poorly maintained trenches and uncomfortable billets. Harold Joseph Hayward’s note in his diary that he was “very cold and fed up”[23] was not an uncommon attitude. Knowledge that they were moving to a particular sector, most notably perhaps the Ypres Salient, could also have a depressing effect on men’s morale.

By contrast, good weather, a bathing party, or a move to rest could prompt positive attitudes towards the war. G. W. Broadhead, for instance, felt “perfectly satisfied” with life once he had “Had a good feed.”[24] Indeed, some men’s enthusiasm for particular aspects of war is reminiscent of Grenfell’s picnic analogy. Kenneth Harman Young (1887-1970), observing the bombardment of the enemy on a clear day, wrote that it was “good to be here to witness these sights.”[25] Military action could often elicit enthusiasm as much as it did fear. M. Holroyd noted in one letter home that “I enjoyed hugely the day of the German attack. Good after being shelled with nothing to do.”[26]

Thus it can be seen that, across the years of the conflict, very few British servicemen held a single attitude, whether of enthusiasm or disillusionment, towards the war. Attitudes varied, contingent upon factors including both the military, such as unit and theatre of service, and the climactic, such as the weather, the amount of sleep or the sector occupied. If, however, there can be said to be a dominant attitude towards the war, it might be classified as determined resignation. As Charles Campbell May (1889-1916) summarised his feelings in his diary:

Conclusion: From Resignation to Disillusionment↑

In his 2008 memoir, The Last Fighting Tommy, written with the assistance of Richard van Emden, Henry John Patch (1898-2009), the last living British First World War veteran to have experienced life in the trenches of the Western Front, wrote:

Patch had been conscripted into the British army at eighteen and served for four months in France before being wounded at Passchendaele and invalided home, where he was still convalescing when the armistice was declared. Yet thanks to his longevity and his eventual ability to tell his story engagingly in public, Patch’s chronicle of disbelief and disillusion with the war became, by the centenary, a significant element in the way in which British soldiers’ attitudes towards the conflict are remembered. The then-Poet Laureate, Andrew Motion, for example, created a universalising narrative out of Patch’s experiences in his poem, The Five Acts of Harry Patch, written as part of a BBC Inside Out programme, broadcast in 2008:

While Patch’s articulation of disillusionment is only one man’s retrospective construction of his attitude to the war, and one which acknowledges to some extent the role that the demobilization process and post-war settlement played in creating such disillusionment, as Motion’s universalising impulse indicates, it reflects the dominant narrative of the attitudes of survivors. This disillusionment is often placed in British narratives of the war in stark contrast to the naivety of the idealistic enthusiasm attributed to early volunteers such as Grenfell.

The process by which disillusion came to be the dominant narrative of men’s attitudes towards the war has been studied extensively by a range of scholars, from the controversies over the “war books” boom of the late 1920s to the convulsions over the use of Blackadder Goes Forth as a teaching aid as recently as 2014.[30] Much of this literature reflects the ways in which, through a range of cultural representations, the war became mythic over the course of the 20th century, as British culture attempted to come to terms with the historic reality of the loss and destruction it entailed.[31] The disillusionment narrative also, however, serves to compress our historic understanding of the many variations in attitude experienced among and by individual men. Both the stoic resignation of men like May and the dedicated, dutiful servicemen like Trench slip from our view when the cultural focus is too narrowly on an accepted category of canonical writers. The experiences of men who, like the character of Robert Fentiman in Dorothy L. Sayers’ (1893-1957) The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (1928), actively enjoyed their experience of war, simply cease to exist in popular memory. Equally, the variations in mood and attitude that all men who served in the war experienced across time are flattened into a single narrative, reflecting Cyril Bentham Fall’s (1888-1971) criticism of the interwar “war books”:

Yet as we have seen, the attitudes reflected and recalled in men’s letters, diaries and even retrospective memoirs were varied and varying. Extremes of enthusiasm and disillusionment existed, although few men occupied either for their entire war service. Similarly, attitudes were shaped by both the carrot and stick of morale-building and discipline, often applied in ways shaped by the civilian identities of the majority of First World War British servicemen. It was in this mixed economy of morale and attitude that some five million men experienced and understood their war service.

Jessica Meyer, University of Leeds

Section Editor: Edward Madigan

Notes

- ↑ Winter, Denis: Death’s Men. Soldiers of the Great War, London 1978, pp. 223-4.

- ↑ Holmes, Richard: Tommy. The British Soldier on the Western Front, 1914-1918, London 2005; Macdonald, Lyn: 1914-1918. Voices and Images of the Great War, London 1991; Liddle, Peter H.: Voices of War. Front Line and Home Front, London 1988.

- ↑ See McCartney, Helen: Citizen Soldiers. The Liverpool Territorials in the First World War, Cambridge 2005; Acton, Carol / Potter, Jane: Working in a World of Hurt. Trauma and Resilience in the Narratives of Medical Personnel in Warzones, Manchester 2015.

- ↑ Winter, J. M.: The Great War and the British People, Basingstoke 1986; Roper, Michael: The Secret Battle. Emotional Survival in the Great War, Manchester 2009.

- ↑ Gregory, Adrian: The Last Great War. British Society and the First World War, Cambridge 2008, p. 33.

- ↑ Grenfell, Julian: Letter to his mother, quoted in: Winter, Death’s Men 1978, p. 224.

- ↑ Sassoon, Siegfried: The Complete Memoirs of George Sherston, London 1937, p. 219.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Wilson, Jean Moorcroft: Siegfried Sassoon. The Making of a War Poet, A Biography 1886-1918, New York 1999, p. 179.

- ↑ McMaster, David Randle: Letter to Mother and Father, 6th August, 1914, Letters of David Randle McMaster, RAMC/023, The Museum of Military Medicine, Aldershot.

- ↑ Blackburn, W.: Letter to Cyril, 1st/3rd July, 1915, Papers of C.T. Newman, Documents.12494, Imperial War Museums (IWM), London.

- ↑ Barlow, G.R.: Letter to Alice, 22nd July, 1918, Papers of G.R. Barlow, Documents.2755, IWM, London; Rawlins, C.S.: Letter to Mother, 31st May, 1915, Papers of C.S. Rawlins, Documents.7314, IWM, London.

- ↑ Gregory: Last Great War 2008, p. 32. See also Pennell, Catriona: A Kingdom United. Popular Responses to the Outbreak of the First World War in Britain and Ireland, Oxford 2012.

- ↑ McDermott, James: British Military Service Tribunals, 1916-1918. ‘A Very Much Abused Body of Men’, Manchester 2011; Pearce, Cyril: Comrades in Conscience. The Story of an English Community’s Opposition to the Great War, London 2001.

- ↑ McCartney, Citizen Soldiers 2005, pp. 162-3.

- ↑ Noyes, Frederick Walter: Stretcher Bearers … at the Double! History of the Fifth Canadian Field Ambulance Which Served Overseas during the Great War of 1914-1918, Toronto 1937, p. 113.

- ↑ Manning, Frederic: Her Privates We, London 2013, first published 1930, pp. 81-2.

- ↑ Babbington, Anthony: For the Sake of Example. Capital Courts Martial 1914-18, London 1983, p. 89.

- ↑ McCartney,: Citizen Soldiers 2005, p. 165.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 162.

- ↑ French, David: Military Identities. The Regimental System, the British Army, and the British People, c.1870-2000, Oxford 2005, pp. 76-98.

- ↑ Trench, Reggie: Letter to Clare, 8th April, 1917, Papers of R.C. Trench, privately held.

- ↑ Hayward, H.J.: Ms. diary, 30th January, 1918, Documents.7141-2, IWM, London.

- ↑ Broadhead, G. W., Ms. diary, 25th June, 1916, Documents.3691, IWM, London.

- ↑ Young, K.H.: Ms. diary, 30th August, 1916, Documents.4796, IWM, London.

- ↑ Holroyd, M.: Letter to unnamed recipient, 6th May, 1915, Letters of M. Holroyd, Documents.7364, IWM, London.

- ↑ May, C. C.: Diaries, 29th January, 1916, Documents.1534, IWM, London.

- ↑ van Emden, Richard / Patch, Harry: The Last Fighting Tommy. The Life of Harry Patch Last Veteran of the Trenches 1898-2009, London 2008, p. 137.

- ↑ Motion, Andrew: ‘The Five Acts of Harry Patch. The Last Fighting Tommy’, 2008, lines 29-33.

- ↑ Fussell, Paul: The Great War and Modern Memory, London 1975; Bracco, Rosa Maria: Merchants of Hope. British Middlebrow Writers of the First World War, 1919-1939, Oxford 1993; Pennell, Catriona: ‘On the Frontlines of Teaching the History of the First World War’, in: Teaching History 155 (2014), pp. 34-40.

- ↑ Hynes, Samuel: A War Imagined. The First World War and English Culture, New York 1991; Todman, Dan: The Great War. Myth and Memory, London 2005; Kempshall, Chris: The First World War in Computer Games, Basingstoke 2015.

- ↑ Falls, Cyril: War Books. A Critical Guide, London 1930, p. xi.

Selected Bibliography

- Acton, Carol / Potter, Jane: Working in a world of hurt. Trauma and resilience in the narratives of medical personnel in warzones, Manchester 2015: Manchester University Press.

- Babington, Anthony: For the sake of example. Capital courts martial 1914-18, New York 1983: St. Martin's Press.

- Bracco, Rosa Maria: Merchants of hope. British middlebrow writers and the First World War, 1919-1939, Providence 1993: Berg.

- Falls, Cyril: War books. A critical guide, London 1930: P. Davies.

- French, David: Military identities. The regimental system, the British Army, and the British people, c. 1870-2000, Oxford 2005: Oxford University Press.

- Fussell, Paul: The Great War and modern memory, Oxford 2013: Oxford University Press.

- Gregory, Adrian: The last Great War. British society and the First World War, Cambridge; New York 2008: Cambridge University Press.

- Holmes, Richard: Tommy. The British soldier on the Western Front, 1914-1918, London 2004: HarperCollins.

- Hynes, Samuel Lynn: A war imagined. The First World War and English culture, New York 1991: Maxwell Macmillan International.

- Kempshall, Chris: The First World War in computer games, Basingstoke 2015: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Liddle, Peter: Voices of war 1914-1918. Front line and home front, London 1988: Leo Cooper.

- Macdonald, Lyn: 1914-1918. Voices and images of the Great War, London 1991: Penguin Books.

- Manning, Frederic: Her privates we, London 2013: Profile Books.

- McCartney, Helen B.: Citizen soldiers. The Liverpool Territorials in the First World War, Cambridge; New York 2005: Cambridge University Press.

- McDermott, James: British military service tribunals, 1916-1918. 'A very much abused body of men', Manchester; New York 2011: Manchester University Press.

- Noyes, Frederick Walter: Stretcher bearers... at the double! History of the Fifth Canadian Field Ambulance which served overseas during the Great War of 1914-1918, Toronto 1937: Hunter-Rose Company.

- Patch, Harry / Van Emden, Richard: The last fighting Tommy. The life of Harry Patch, the oldest surviving veteran of the trenches, 1898-2009, London 2008: Bloomsbury.

- Pearce, Cyril: Comrades in conscience. The story of an English community's opposition to the Great War, London 2001: Francis Boutle Publishers.

- Pennell, Catriona: A kingdom united. Popular responses to the outbreak of the First World War in Britain and Ireland, Oxford 2012: Oxford University Press.

- Pennell, Catriona: On the frontlines of teaching the history of the First World War, in: Teaching History 155, 2014, pp. 34-41.

- Roper, Michael: The secret battle. Emotional survival in the Great War, Manchester; New York 2009: Manchester University Press.

- Sassoon, Siegfried: The complete memoirs of George Sherston, London 1937: Faber and Faber.

- Simkins, Peter: Kitchener's army. The raising of the new armies, 1914-1916, Manchester; New York 1988: Manchester University Press.

- Todman, Daniel: The Great War. Myth and memory, London 2005: Hambledon Continuum.

- Wilson, Jean Moorcroft: Siegfried Sassoon. The making of a war poet. A biography (1886-1918), New York 1999: Routledge.

- Winter, Denis: Death's men. Soldiers of the Great War, London 1978: Allen Lane.

- Winter, Jay: The Great War and the British people, London 1985: Palgrave Macmillan.