Introduction↑

The experience of personal bereavement was shared by thousands of New Zealand households during the First World War, illustrating the ability of the war to profoundly disrupt the lives of individuals and families in locations far removed from the scene of hostilities. During the First World War, New Zealand mobilised a total of 124,211 men and sent 100,144 overseas as part of its expeditionary force. Of these, more than 18,100 had died of injury or illness by 1923.[1] More would succumb to war-related causes after this date. This represented a significant death toll for a country whose population numbered just over 1 million in 1914. Although only one among many, each individual war death was "a personal tragedy" which impacted not only a man’s immediate family but reverberated through neighbourhoods and wider communities.[2]

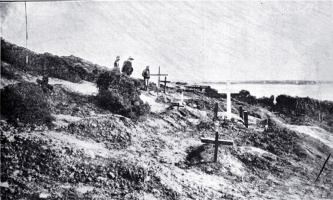

It was not only the scale of death, but the nature of the losses that made deaths during the First World War so profoundly traumatic. Deaths in the war predominantly involved healthy adult men. They were frequently violent. At Gallipoli, the majority of victims were buried in mass graves, which were not revisited until the Allies and their grave identification units returned to the peninsula in 1919. On the Western Front, the destructive nature of shell warfare on men’s bodies meant that many remains would never be identified, while other men’s remains were initially located but later lost during subsequent fighting. Of the 2,721 New Zealand servicemen who died at Gallipoli, 67 percent of bodies were never recovered, and of the 12,483 New Zealand men who lost their lives on the Western Front, 33 percent were not located.[3] Lastly, the majority of wartime deaths took place far away from home and family. During the First World War, New Zealand followed the British and Empire policy of not repatriating the war dead. Instead, the remains of New Zealand soldiers who died in the war were buried in military cemeteries constructed around former battlefields. Those soldiers whose bodies were not recovered were individually named in "memorials to the missing" erected in Allied cemeteries near to where the men had been killed. The graves of unidentified soldiers were simply marked "A Soldier of the Great War Known Unto God".[4]

Existing studies by historians such as Sandy Callister, Graeme Hucker, Kate Hunter and Kirstie Ross, Jock Phillips and Chris Maclean shed light on grief and bereavement in New Zealand during the First World War.[5] We can also draw insights into New Zealanders’ responses to wartime deaths through comparable Australian and British studies. In particular, recent work on the subject of private grief in the Australian context points to the problems that distance posed for bereaved families in wartime – a phenomenon also experienced by New Zealand mourners.[6] As demonstrated by this scholarship, New Zealanders’ responses to grief and bereavement in wartime reflected mourners’ desire to achieve continuity with pre-war civilian cultural practices and rituals surrounding death, but in the face of circumstances that forced many of these familiar rites to be adapted, if not abandoned altogether. During the war, individual soldiers’ deaths became absorbed into an impersonal rhetoric of heroic death and imperial sacrifice. Bereaved individuals and families participated in and drew solace from these widely circulated narratives, but also resisted them. Christian consolation and the values of duty and service were central to the attempts of both soldiers and members of home front communities to make sense of wartime losses.[7] Aspects of New Zealanders’ experience of wartime grief and bereavement covered in the present article include pre-war cultural practices surrounding death and bereavement, families’ efforts to seek out details of their loved one’s deaths, the forms consolation took, newspaper coverage of wartime losses, the plight of families of the missing, the role of material objects in the grieving process, and families’ relationships with distant war graves.

Pre-war Cultural Practices Surrounding Death and Bereavement↑

Early 20th century Pakeha (European) New Zealanders observed a wide range of rituals surrounding death and bereavement. These included the preparation of the body, the holding of a funeral, a cemetery burial and the ritual of grave visiting. Women in mourning signalled their special status through the wearing of black mourning clothes. Friends and family responded to the news of a death by calling upon or sending letters or cards of condolence to the immediate family of the deceased.[8] Such practices "channelled the pain of loss, and signified a changed relationship between the bereaved household and the wider community".[9] Christian faith formed a central part of the efforts of Pakeha colonists to come to terms with bereavement.[10] In Māori culture, the tangihanga (funeral ceremony) involved the return of the tūpāpaku (body) to the marae (meeting house) and offered the opportunity for whānau (families) and their wider kinship group (hapū) to gather together and bid farewell to the body and spirit of the deceased.[11] The form that these cultural practices and beliefs surrounding death took varied greatly between Pakeha and Māori cultures. But for both Pakeha and Māori mourners, the observance of such rites was essential to the process by which they were able to express grief and begin to come to terms with their losses.[12] The fact that the majority of deaths in the First World War occurred so far away from home and family rendered many of these familiar and comforting rituals surrounding death impossible.

Seeking the Details of a Loved One’s Death↑

In New Zealand, next-of-kin typically received the news of a soldiers’ death by official telegram, delivered by a telegram boy on a bicycle. One of the first priorities for recently bereaved families was to obtain as full as possible an account of the circumstances surrounding a soldier’s death and burial. After Gisborne man George Harry Black (1885-1916) was killed in France, his brother Ernest Richard Black (1888-1970) asked an officer friend to: "Reply by return post and let me know the true details of what happened to George’s body. I don’t expect to hear that he was decently buried; but tell me the truth."[13] Later Ernest Richard Black was able to obtain further information on his brother’s death from a fellow soldier: "I had seen a man named Lewis, who was with George when he was first hit, and he gave me many details."[14] Soldiers considered it a duty to write to the family of a deceased serviceman to relay "all important details" surrounding their loved one’s death.[15] Despite the ubiquity of death on the frontlines, soldiers felt the deaths of their own particular friends keenly.[16] After the death of Hamilton man John Fleming Keith Hunter (1893-1916) in France in 1916, a fellow soldier wrote to his relatives: "He was my greatest friend in France. For nearly six months we lived and worked together, and during that time we did not exchange one angry word."[17]

Soldiers’ letters to the relatives of their comrades represented attempts to make sense of men’s deaths and to console their families, in terms of widely shared Victorian values such as duty, character and valour.[18] After John Matthew Todd (1876-1915) was killed in Egypt on Christmas Day 1915, a fellow soldier emphasised his courageous conduct leading up to his death in a letter to his widow Elizabeth: "Rifleman Todd was quite 10 yards in advance of the others of his section when he was struck by a bullet in the right side of the abdomen and killed almost instantly. Mrs Todd, though so sadly bereaved, may well be proud."[19] Such descriptions of men’s deaths as quick and painless were commonplace in soldiers’ letters to the families of deceased men, and are likely more indicative of the writer’s desire to spare relatives from anguish, than an accurate description of the circumstances surrounding a man’s death. A letter written by Private Andrew Edmond "Ted" McMahon (1885-1937) to the father of his fellow soldier Private Harold Wilkinson (1893-1915) shows how narratives of collective sacrifice could be expanded to include a soldier’s relatives. Following Wilkinson’s death in France, McMahon wrote to Wilkinson’s father: "I know you must feel deeply at your loss but I know also that as a man you will live through it and it may be that when the first soreness wears off you will lift your head a little higher, for what greater sacrifice could you make?"[20] In other soldiers’ letters, Christian faith formed the primary frame of reference. Following the death of James McGarrigle (1882-1916), his friend G. Bickart wrote to his mother: "Mere words cannot express my feelings for you and yours in the dark hour that is now yours...I hope and trust that the Spirit above will comfort you and give you strength in this sad bereavement."[21]

Home front Consolation: An Otago Case Study↑

It was not only fellow soldiers who wrote to families following a death in combat. On the home front, the friends, kin and acquaintances of the immediate family of the deceased responded to the news of a soldier’s death according to pre-war custom: by sending messages of condolence to the bereaved family. A significant collection of over 300 condolence letters received by one grieving Otago family provides a window into the forms that such home front expressions of consolation took.[22] George Hepburn Stewart (1875-1915) died of dysentery on the Greek island of Lemnos in November 1915, while his regiment was on leave from the Gallipoli campaign. The foremost values which emerge in the condolence letters received by this upper-class Presbyterian family are of Christian faith and the ideals of duty and service. Over 30 percent of the letters in the collection contained religious content. These voiced hope that God would give comfort or strength to the bereaved relatives in their time of need, or simply stated that the writer’s prayers would be with the family. Others expressed the belief that soldiers killed in the war had gone to a "better place", or wrote of the consolation offered by the prospect of heavenly reunion.[23] A family friend wrote of her sadness for George Stewart’s widow Elizabeth: "They had such a short time of happiness together, but they will meet again – all this sorrow has made that clear to us – the next world is very near & I am sure our loved ones are permitted to help us, & we know they have passed from Death into life."[24] Duty, service and sacrifice were also prized highly among the mainly upper- and middle-class letter writers in this collection, with 22 percent of condolence letter writers referring to one of these terms in their letters. During the war, notions of masculine duty became inextricably connected to military service. However, while letter writers in this collection linked attributes such as duty and service to George Stewart’s death on military service, they also regarded them as traits animating his entire life. One friend wrote: "In leaving home & country to fight for King & Empire, he showed a spirit of self-sacrifice that enobled his whole life & on this account the regret we feel at his death is the more poignant and heart-felt."[25] While thirty-six correspondents in this collection highlighted George Stewart’s qualities as a soldier and officer, eighty-two letters described his attributes as a friend and colleague.[26] Thus, this collection of condolence letters shows how men’s pre-war civilian identities could co-exist alongside their military identities as soldiers or officers in wartime expressions of consolation (rather than being supplanted by them).

Private Bereavement Becomes Public Knowledge: Newspaper Coverage of Deaths↑

The wartime practice of publishing official lists of casualties and those listed as missing in local newspapers provided a mechanism for an individual family’s loss to be made known to their wider community. The perusal of such newspaper casualty lists for a familiar name became a common ritual for many New Zealanders during wartime. From 1915, weekly newspapers such as the Otago Witness and the Auckland Weekly News regularly published illustrated casualty lists containing portraits of the dead, wounded or missing as part of visual Rolls of Honour.[27] A commemorative issue of the Auckland Weekly News from October 1915 contained "4000 photographs" of New Zealand soldiers killed or wounded in the war.[28] In addition, some soldiers’ relatives placed their own individual "In Memoriam" notices in local newspapers. These frequently included epitaphs expressing Christian or imperial sentiment, and emphasising the families’ pride that their son, husband or brother had died "doing his duty".[29] From mid-1915 onwards, the publication of "biographicals" of soldiers who had died in the war became common practice in local newspapers.[30] Such biographicals drew upon militarised narratives of imperial glory but also highlighted men’s achievements in the civilian realms of education, sport, clubs or professional lives. Thus, as Hunter has argued, such biographicals represented an attempt on the part of families to reclaim their own men from the rhetoric of imperial sacrifice and the noble death.[31]

The Plight of Families of the Missing↑

The sense of closure that some families’ experienced from obtaining details of their loved one’s deaths was either temporarily or permanently suspended in the case of the relatives of soldiers reported "missing." For such families, the arrival of a notification of "missing" often marked the beginning of what could be a lengthy and frequently fruitless search for more information. Families sought this news through both formal and informal channels. Official channels included the sending of cabled enquiries through to the office of the New Zealand High Commissioner in London, or through making enquiries through volunteer organisations such as the Red Cross.[32] Informal channels could include placing advertisements in newspapers or writing to the fellow comrades of a deceased soldier.[33] The family of Augustine Bond (1890-1915) waited six years until they finally learnt of his fate. On 21 June 1915, Bond’s father had received the news that his twenty-four-year-old son had been wounded on Gallipoli but was "progressing favourably".[34] The father’s efforts to trace his son in both Egypt and England failed and in April 1916 a military inquiry concluded that Bond had most likely been killed on Gallipoli.[35] Confirmation of Augustine Bond’s death finally arrived in February 1922 when his body was removed "from an isolated grave and laid to rest in Baby 700 Cemetery, Gallipoli."[36] However, many families never received such closure. When the New Zealand Red Cross’s "Enquiry Bureau for the Killed & Missing" closed around 1919, more than 400 cases remained "unfinished."[37]

Objects of Mourning↑

In the absence of graves and bodies of the dead to mourn, bereaved families invested even greater significance in physical objects and mementoes associated with the deceased soldier.[38] Prior to men’s departure for war, it was a common practice for individual soldiers or soldiers and their families to visit commercial photographic studios like Wellington’s Berry & Co. studios.[39] In the event that a soldier did not return, such portraits became "artefacts of mourning and memory."[40] In some family homes, soldiers' portraits formed the centre of private shrines to the dead.[41] After the death of Sergeant Henry Thomas Norton (1881-1916) his widow and children dedicated a corner of their living room to a shrine to his memory, including his portrait and other items.[42] Frances Rolfes (1864-1930) carried a miniature portrait of her soldier son, killed in 1918, in her purse for the remainder of her life.[43] Objects associated with the body or grave of the deceased also became treasured keepsakes for families. Following the death of Harold Wilkinson in 1916, fellow soldier Ted MacMahon "thoughtfully forwarded the dead soldier’s Bible and some other articles which will now become treasured possessions."[44] In the case of Auckland soldier Percival Harcourt Haresnape (1881-1916), killed at the Battle of the Somme, a faded wristwatch engraved with his name provided both the means of identifying his body and a treasured keepsake for his family: the fact of its safe delivery to his family back in New Zealand providing testimony of "honour that even the bodies of our heroes are given."[45] In the years during and after the First World War, local communities around New Zealand invested considerable effort and funds into the construction of local memorials to the dead. The unveiling of such memorials were major community events, frequently attended by local mayors, members of parliament and other dignatories as well as members of the local population. Such memorials could provide a focal point for relatives’ grief and even act as ‘a surrogate tomb’ for distant war graves overseas.[46]

Families’ Relationships with Overseas War Graves↑

As historian Bart Ziino has found in the Australian context, the desire of bereaved New Zealanders to form bonds with the graves of loved ones buried overseas was not cancelled out by distance. Instead, bereaved relatives channelled considerable emotional energy into establishing connections with overseas war graves. In New Zealand, as elsewhere in the British Empire, the government accepted that the construction and maintenance of the graves of men who died in the war should be the responsibility of the state. The Imperial (later Commonwealth) War Graves Commission, founded in 1917, was charged with the construction and ongoing upkeep of the graves of the war dead of the British Empire. The Commission was funded through endowments from member governments and, by late 1923, New Zealand’s share in the finances of the Imperial War Graves Commission amounted to £92,691.[47]

In the years following the end of the First World War, some New Zealand families were fortunate enough to make the pilgrimage to visit the graves of loved ones buried overseas. However, the vast distances involved and the cost of such travel proved prohibitive for most. In the interwar period, some New Zealand families sought government help to make such journeys, believing that their participation in the "collective sacrifice" of the war should entitle them to such assistance from the state. Members of parliament, government departments and voluntary organisations such as the Returned Soldiers’ Association (RSA) fielded many such enquiries from families seeking advice or assistance to visit foreign war graves during the 1920s and 1930s. For instance, in 1922, the secretary of the Dunedin RSA wrote to the department of internal affairs for confirmation of the government’s policy regarding assisted passage for relatives wishing to visit war graves in Western Europe and Gallipoli, having "had several enquiries lately with regard to passages to such intending visitors."[48] After the end of the war, a delegation of Northland’s Nga Puhi iwi (tribe), accompanied by their MP the Hon Taurekareka (Tau) Henare (1877/1878–1940), travelled to the capital in Wellington to petition the minister for native affairs to supply two troop transports "to take the next of kin of Māoris fallen to France to visit the graves of their relatives to perform the customary rites." The article explained: "An ancient Māori custom is that relatives of soldiers fallen in battle must perform certain rites over the graves of their loved ones to ensure their happiness in the next world."[49] However, the request was turned down lest it create a precedent for other families.[50] In the end, the New Zealand government made no official provision to assist the families of servicemen who died in the First World War to visit overseas war graves.[51] However, for those families who managed to make it to Europe unassisted, the New Zealand authorities did offer advice to "facilitate bereaved relatives in visiting the graves", via the New Zealand High Commissioners’ Office in London and the New Zealand Red Cross.[52]

As Ziino has found in Australia, those families who were able to visit overseas military cemeteries in person acted as ambassadors for other families back in New Zealand.[53] Accounts of their journeys published in New Zealand newspapers provided relatives back in New Zealand with descriptions of the work being carried out in military cemeteries abroad, or offered reassurances that their loved one’s graves were being well cared for. An Otago couple returned from one such pilgrimage to France in March 1932 "anxious to convey to parents and relations of those who fell the information that the graves and burial grounds in every instance are maintained in beautiful condition. They state that if parents and relatives themselves were attending to the graves they could scarcely improve the conditions which obtain."[54] Volunteer organisations such as the Red Cross also sought to facilitate families’ relationships with distant war graves. During 1926, for instance, the Christchurch branch of the Red Cross invited families to view a film screening of a "Pilgrimage to War Graves in France" and lantern slides of Gallipoli graves.[55] The New Zealand government also assisted in relatives’ efforts to visualise the graves of soldiers buried overseas by forwarding photographs of individual graves to soldiers’ next-of-kin as soon as the work on each battlefield cemetery was completed.[56]

Conclusion↑

Grief and bereavement during the First World War was at once a collective and a highly personal experience. Thousands of New Zealand families were affected by wartime losses, yet the fact that their experience was repeated many times over during the war did not diminish families’ sense of individual grief. Bereaved individuals and families sought comfort and meaning from a range of sources. As before the war, Christian faith formed an important component of families’ responses to bereavement, offering comfort or holding out the hope of a heavenly reunion. Soldiers’ relatives also drew solace from the knowledge that their loved one had died "doing their duty" and for a noble cause, and soldiers’ family members were also viewed as part of this collective "sacrifice". However, individual gestures by mourners, such as the placement of memorial notices in newspapers or the writing of condolence letters, were also indicative of a desire to reclaim individual men’s lives and identities from militarised narratives of heroic death and mass sacrifice. The experience of bereavement in the First World War was defined, above all, by the absence of remains over which to mourn. In the absence of bodies, physical objects or personal possessions associated with the deceased gained even greater significance. New Zealand families were not deterred by remoteness in their efforts to maintain relationships with the graves of soldiers buried on foreign soil: instead, families invested considerable energy into forming emotional and imagined bonds with the distant war graves of loved ones overseas.

Rachel Patrick, Victoria University of Wellington / Waitangi Tribunal

Section Editor: Kate Hunter

Notes

- ↑ Crawford, Ian / McGibbon, Ian: Introduction, in: Crawford, Ian / McGibbon, Ian (eds.): New Zealand’s Great War. New Zealand, the Allies & the First World War, Auckland 2007, pp. 16-17.

- ↑ Hunter, Kate / Ross, Kirstie: Holding On To Home. New Zealand Stories and Objects of the First World War, Wellington 2014, p. 211.

- ↑ Known Unto God, issued by New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage, online: [1] (retrieved: 10 August 2014).

- ↑ Ziino, Bart: A Distant Grief. Australians, War Graves and the Great War, Crawley (Western Australia) 2007, p. 3.

- ↑ For details of these authors’ works, refer to the reference list at the end of the article.

- ↑ Ziino, Distant 2007.

- ↑ Hunter, Kate: ‘Sleep on dear Ernie, your battles are o’er’. A Glimpse of a Mourning Community, Invercargill, New Zealand, 1914-1925, in: War in History 14/1 (2007), p. 61; Patrick, Rachel: An Unbroken Connection? New Zealand Families, Duty, and the First World War, PhD Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington 2014, chapter four.

- ↑ Jalland, Pat: Australian Ways of Death. A Social and Cultural History 1840-1918, Melbourne 2002, pp. 127, 145; Hunter, Sleep 2007, p. 43; Hunter / Ross, Holding 2014, pp. 211f.

- ↑ Porter, Frances / Macdonald, Charlotte (eds.): My Hand Will Write What My Heart Dictates. The Unsettled Lives of Women in Nineteenth Century New Zealand as Revealed to Family and Friends, Auckland 1996, p. 453.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 452.

- ↑ Higgins, Rawinia / Moorfield, John C.: Tangihanga. Death Customs, in: Ka’ai, Tania (ed.): Ki Te Whaiao. An Introduction to Māori Culture and Society, Auckland 2004, pp. 85-90.

- ↑ Porter / Macdonald, Hand Will Write 1996, p. 453.

- ↑ Hocken Library, Dunedin, William Downie Stewart papers, MS-0985-003/013.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Hunter, Sleep 2007, p. 50.

- ↑ Hunter, Sleep 2007, pp. 46-49.

- ↑ The Late Capt. Keith Hunter, in: Waikato Times, 20 December 1916, p. 6.

- ↑ Hunter, Sleep 2007, p. 49.

- ↑ Local and General, in: Dominion, 15 June 1916, p. 4.

- ↑ A Soldier’s Death, in: Northern Advocate, 15 December 1916, p. 2.

- ↑ Dear Dug-Out Pal, in: Waikato Times, 16 November 1916, p. 6.

- ↑ Patrick, Unbroken 2014, chapter four.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 127-131.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 129.

- ↑ Hocken Library, Dunedin, William Downie Stewart papers, MS-0985-033/001.

- ↑ Patrick, Unbroken 2014, p. 136.

- ↑ Callister, Sandy: The Face of War. New Zealand’s Great War Photography, Auckland 2008, p. 75.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Hunter, Sleep 2007, p. 52.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 53.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 39.

- ↑ Patrick, Unbroken 2014, p. 81.

- ↑ Hunter, Kate: Australian and New Zealand fathers and sons during the Great War. Expanding the histories of families at war, in: First World War Studies 4/2 (2013), p. 190.

- ↑ New Zealand’s Roll of Honour, in: New Zealand Herald, 22 June 1915, p. 9.

- ↑ Personnel file of Augustine Bond, issued by Archives New Zealand, Wellington, online: [2] (retrieved: 30 August 2014).

- ↑ In Memoriam, in: New Zealand Herald, 13 July 1922, p. 1.

- ↑ Archives New Zealand, Wellington, IA1-1663-32-1-54.

- ↑ Hunter / Ross, Holding 2014, chapter eight.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Michael / Regnault, Claire: Berry Boys. Portraits of First World War Soldiers and Families, Wellington 2014.

- ↑ Callister, Face 2008, p. 6.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 124f.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 114ff.

- ↑ Hunter / Ross, Holding 2014, p. 222.

- ↑ A Soldier’s Death, in: Northern Advocate, 15 December 1916, p. 2.

- ↑ For Remembrance, in: New Zealand Herald, 24 April 1926, p. 1.

- ↑ Maclean, Chris / Phillips, Jock: The Sorrow and the Pride. New Zealand War Memorials, Wellington 1990, p. 70.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Department of Internal Affairs for 1924, in: Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives, H-22, p. 7, available through AtoJsOnline, National Library of New Zealand, Wellington.

- ↑ Archives New Zealand, Wellington, IA1-1689-32/3/29, part 2.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Sacred Graves, in: New Zealand Herald, 25 February 1920, p. 5; Archives New Zealand, Wellington, IA1-1689-32/3/29, part 2; Location of soldiers’ Graves Overseas, in: Evening Post, 10 November 1920, p. 7.

- ↑ Ziino, Distant 2007, p. 163.

- ↑ New Zealand War Graves: in, Auckland Star, 1 March 1932, p. 3.

- ↑ Archives New Zealand, Wellington, IA1-1663-32-1-54.

- ↑ Where Heroes Sleep, in: New Zealand Herald, 12 September 1925, p. 12.

Selected Bibliography

- Callister, Sandy: The face of war. New Zealand's Great War photography, Auckland 2008: Auckland University Press.

- Damousi, Joy: The labour of loss. Mourning, memory, and wartime bereavement in Australia, Cambridge; New York 1999: Cambridge University Press.

- Higgins, Rawinia / Moorfield, John C.: Tangihanga. Death customs, in: Ka'ai, Tania (ed.): Ki te whaiao. An introduction to Māori culture and society, Auckland 2004: Pearson Longman, pp. 85-90.

- Hucker, Graham: The rural home front. A New Zealand region and the Great War 1914-1926, Palmerston North 2006: Massey University.

- Hunter, Kate: Australian and New Zealand fathers and sons during the Great War. Expanding the histories of families at war, in: First World War Studies 4/2, 2013, pp. 185-200.

- Hunter, Kate: ‘Sleep on dear Ernie, your battles are o’er.’ A glimpse of a mourning community. Invercargill, New Zealand, 1914-1925, in: War in History 14/1, 2007, pp. 36-62.

- Hunter, Kate / Ross, Kirstie: Holding on to home. New Zealand stories and objects of the First World War, Wellington 2014: Te Papa Press.

- Jalland, Patricia: Australian ways of death. A social and cultural history, 1840-1918, Melbourne; New York 2002: Oxford University Press.

- Liebich, Susann: Connected readers. Reading practices and communities across the British Empire, c. 1890-1930, thesis, Wellington 2012: University of Wellington.

- Maclean, Chris / Phillips, Jock: The sorrow and the pride. New Zealand war memorials, Wellington 1990: GP Books.

- Patrick, Rachel: 'Speaking across the borderline'. Intimate connections, grief and spiritualism in the letters of Elizabeth Stewart during the First World War, in: History Australia 10/3, 2013, pp. 109-128.

- Patrick, Rachel: An unbroken connection? New Zealand families, duty, and the First World War, thesis, Wellington 2014: Victoria University of Wellington.

- Porter, Frances / MacDonald, Charlotte / MacDonald, Tui (eds.): My hand will write what my heart dictates. The unsettled lives of women in nineteenth-century New Zealand as revealed to sisters, family and friends, Auckland 1996: Auckland University Press.

- Worthy, Scott: A debt of honour. New Zealanders' first Anzac days, in: New Zealand Journal of History 36/2, 2002, pp. 185-200.

- Ziino, Bart: A distant grief. Australians, war graves and the Great War, Crawley 2007: University of Western Australia Press.