Introduction↑

Colonial rule spread Western ideas, values, and practices to African culture beginning in the latter half of the 19th century. The colonial influence on African culture was particularly evident during World War I, when the wartime experiences of African families and soldiers led to major changes in African ideas, beliefs, and practices pertaining to illness, death, burial, and remembrance. More than 2 million Africans participated in World War I and around 200,000 African soldiers and carriers lost their lives during military service.[1] As a result of African participation and experience in the war, many African families began to adopt Western mourning practices related to grieving, burying, and remembering the dead. However, the nature and trajectory of change in the African mode of grieving was not uniform: some continued to follow traditional African customs while others adopted entirely Christian or Western customs; others intermingled the two traditions.

Traditional African Beliefs and Practices↑

Africans universally believed that life was sacred and that every person had a right to proper treatment and care in life and death. The vast majority of Africans believed in treating the ill, the injured, the dying and the dead with care. However, different African communities - ethnic, regional, and religious, to mention only a few - traditionally dealt with matters of illness, death, bereavement, and mourning in different ways. The way the Yoruba of Nigeria mourned, grieved and remembered the dead[2] was not always the same as that of the Gikuyu of Kenya.[3] Take for example, the manner in which the Nandi of Kenya and the Igbo of Nigeria handled the bodies of the dying and the dead: the Nandi would often move the very ill and dying out of their homesteads to be left out in a faraway open field. If a sick person recovered from this ordeal, they would be welcomed back into the homestead, but, if they died, the body would be left for the hyenas to devour.[4] The Igbo kept the ill and dying within the homestead to receive treatment until they died or recovered. If a person died, they would be buried in a grave within the homestead. Yet, in spite of these differences, there were certain shared overarching characteristics in African beliefs and practices regarding illness, death, bereavement, and remembrance of the dead.[5]

Nearly all African communities regarded illness and death with great trepidation. Human beings were expected to live and enjoy a normal life until death in old age and many African families believed that an early death was not a natural occurrence. Anything that interfered with the natural course of life and brought about illness or premature death was believed to be caused by sorcery or evil spirits.[6] Consequently, Africans took elaborate measures including traditional ceremonies to ward off illness, death, and bereavement, also during wartime.[7]

During World War I, many African families provided their soldiers with charms and amulets to protect them from harm, invited elders to offer blessings, and beseeched religious leaders and medicine men to make sacrifices and offerings to the gods to guide soldiers during their military service.[8] If an African soldier contracted an illness or was injured, his family did everything within its power to arrange treatment by consulting with traditional medicine men and religious leaders and begging them to save the life of the injured or ailing soldier.

Many African families took such steps caring for the ill and the injured not only out of love, but also out of a strong belief in life after death; more specifically, the belief of power of the dead over the living. Nearly all African communities believed that when somebody died, their spirit passed on to another world where they could continue communing with the living, dispensing favors and misfortune. The Igbo, for example, believed that their ancestors lived amongst them, “a permanent presence among the living: he or she is an onlooker, giving rewards or punishment according to the behavior of the living.”[9] The Abanyole, a sub-group of the Abaluhya of Kenya, also believed that the spirits of the dead were capable of rewarding or punishing the living.[10]

African families often tried to ensure that the dead were given a proper burial and their families were provided with moral, material, and spiritual support. Death was an occasion for every member of the community to come together to mourn, remember, commiserate, and send off the spirit of the dead into the next world.[11] Nearly all African communities believed in burying the dead in their ancestral land, where the spirit of the dead would join with the spirit world. Among Ghana’s Ashanti, families, relatives, and members of the community would mourn at the homestead of the deceased. During such occasions, the Ashanti performed solemn rites on the dead, offered sacrifices in his memory, and participated in elaborate burial ceremonies.[12] Every able-bodied, adult member of the Ashanti community was generally expected to attend burial ceremonies because it was believed that the dead would notice those present and those absent and would offer their blessings and curses accordingly. The Abanyala sub-group of the Abaluhya of Kenya performed ceremonies commemorating the end of mourning by slaughtering and eating chickens and cows at the homestead of the deceased. Among the Baganda of Uganda, “the state of mourning or ‘death’ (olumbe) was ended by a ceremony called ‘destroying death’ (okwaabya olumbe). This ceremony involved the eating of a chicken by the male relatives who gathered in the house of the deceased.”[13]

Apart from performing elaborate funeral ceremonies, members of African communities also took other measures to commemorate the dead. The Nyau Society among the Chewa of Malawi staged complex masquerade ceremonies complete with death masks to commemorate death and other important social occasions. The Luo of Kenya named their children after the dead believing that this was one of the best ways to keep their memory alive. The Shona and the Ndebele of Zimbabwe built shrines for the spirit of the dead in their homes.[14] Many African communities observed mourning, bereavement, and remembrance ceremonies that sometimes lasted for weeks, months, even years. They remembered the dead by invoking their names during such ceremonies, conducting libation rituals, and holding ceremonies naming the living after the dead.[15] How, then, did Africans mourn, bury, and remember dead soldiers during and after World War I, and how did these customs and practices change during the period?

Mourning and Remembrance During and After World War I↑

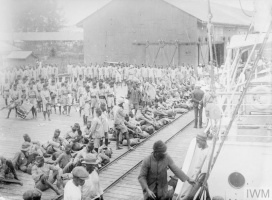

African soldiers served in World War I mostly in the armies of the British, French and German colonial powers, some as volunteers, but the overwhelming majority as conscripts. While some soldiers served as combatants on the frontlines, the majority served as carriers (porters). Many were killed in combat in Africa and Europe and many more were killed by health problems brought about by exhaustion, exposure to the elements, and disease.[16] It has been estimated that about 1,800 African soldiers in the German Schutztruppe and about 1,377 African soldiers on the British side were killed in combat during the East African Campaign.[17] About 30,000 African soldiers were killed while serving in the French army in Europe.[18] Of the nearly 2 million African soldiers who served in World War I, almost 200,000 died during the war.[19] In East Africa alone, nearly 1 million African servicemen were involved in the war in one way or another, and about 10 percent of them lost their lives. “The total mortality rate” among East African men “was well over 100,000.”[20]

Many African families were shocked by the sheer number of casualties and deaths. Africans in Senegal characterized World War I as “‘a very, very bad thing’ or as ‘the worst thing I ever saw’.”[21] Those in Malawi equated the war with tengatenga - military labor.[22] Others in East Africa associated the war with military labor units such as the Carrier Corps (Kariokor) and death.[23] Indeed, years after the war ended, many Africans continued to remember the war as a very destructive event that took the lives of many of their people.

There is no doubt that the death of African soldiers and carriers during World War I was extremely painful for their families back home, as the experience of Senegalese families demonstrates:

Nevertheless, the modes of mourning and burial of dead African soldiers across and beyond Africa during the war were not uniform. Many families performed funeral rites for their dead soldiers in line with traditional African practices; others changed certain aspects of their traditions; while others completely adopted western and Christian modes of mourning and burying the dead.

Among the Chewa, who upheld traditional practices and funerary rites, bereaved families would often invite members of the feared Nyau Society to perform death rituals at funerals during and after World War I.[25] Among traditional Luo families, respected family members of the deceased and community elders would lead the family in mourning. Members of the community would visit the dead soldier’s home, singing his praises and reciting dirges while condemning the evil spirits for taking away a great member of their community. Young and elderly men would run helter-skelter about the dead man’s homestead, wielding spears and shields and bows and arrows, in mock battles with the evil spirits. Members of the community would slaughter animals to feed mourners attending the funeral and to pay homage to the dead soldier’s memory. Families observing traditional rites believed that doing otherwise could invite curses from the dead soldier, and misfortune would follow for the community at large.

Many African families performed traditional funeral rites without the bodies of the dead as many African soldiers died far away from home, in places where bodies could not be retrieved. In such situations, families were often compelled to conduct funeral rites for their dead soldiers in accordance with their traditional customs. The Luo, for example, usually buried the fruit of the yago (Kigelia africana) tree in a grave in the dead soldier’s homestead in the same manner they would have buried his body. Other African families ceremonially buried various types of objects to represent and commemorate the death of their soldiers whose bodies were absent. Such families also remembered the dead soldiers by naming children born in the community after them.

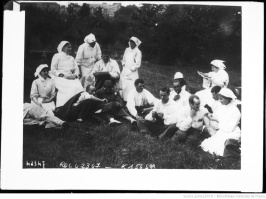

The experience of African families and soldiers during the war, in particular, and under colonialism, in general, led to major changes in African ideas, beliefs, and practices pertaining to illness, death, burial, and remembrance. We see this change during and after World War I, when, for example, African families that had converted to Christianity and adopted Western customs began to bury their dead soldiers in the Christian style. Exactly how many Africans had converted to Christianity during the early colonial period is not clear. It is clear, however, that when families had converted to Christianity, they often observed Christian rituals and practices during burial ceremonies. Among the Zulu Christian converts, for example, many bereaved families would invite, not their traditional elders, but, rather, an ordained minister to lead the mourners in grieving and burying the dead. The minister would lead the mourners in reading Bible passages, singing Christian hymns, and blessing the soul of the dead person before he was buried according to Christian tradition.

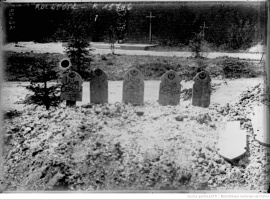

African families also yielded authority to the colonial military officials to bury their dead in war cemeteries both in Africa and Europe.[26] Instead of insisting on traditional ceremonies, they began to accept and observe colonial military customs. In the same vein, African families began to recognize colonial monuments built to honor and glorify the sacrifices and heroic accomplishments of living and dead African soldiers during the war. African families in Kenya, for example, were often in awe of the statue of three soldiers that stands on Kenyatta Avenue in Nairobi, Kenya, a monument built in honor of the East African contingent of the British army. While some African families perpetuated traditional modes of mourning and others adopted Western practices, still others tried to straddle both traditional and western spaces in funerary customs and other facets of life. Such families were very common.

Conclusion↑

Over the course of World War I, African families mourned, buried, and honored dying and dead soldiers with both traditional and Western/colonial practices. This article has offered some thoughts on how Africans traditionally dealt with illness, injuries, and death as well as the ways in which new modes of mourning were integrated into African culture, laying groundwork for further studies of the mourning and commemoration of African soldiers during World War I.

Meshack Owino, Cleveland State University

Section Editors: Melvin E. Page; Richard Fogarty

Notes

- ↑ Strachan, Hew: The First World War in Africa, Oxford 2004, p. 3.

- ↑ Falola, Toyin: Culture and Customs of Nigeria, Westport 2001, p. 35.

- ↑ Kenyatta, Jomo: Facing Mt. Kenya, London 1962, p. 4.

- ↑ Snell, G. S.: Nandi Customary Law, Nairobi 1986, p. 74. See also: Hollis, A.C.: The Nandi: Their Language and Folk-lore, Oxford 1909.

- ↑ Mbiti, John S.: Introduction to African Religion, London 1975, pp. 116-130.

- ↑ For example the Gikuyu and the Azande of South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo: Kenyatta, Jomo: Facing Mt. Kenya, p. 260 and Evans-Pritchad, E.E.: Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic among the Azande, Oxford 1976, p. 18.

- ↑ Smith, Robert S.: Warfare and Diplomacy in Pre-Colonial West Africa, Madison 1976, p. 33.

- ↑ Lunn, Joe: Memoirs of the Maelstrom: A Senegalese Oral History of the First World War, Portsmouth and New Haven 1999, p. 42.

- ↑ Falola, Toyin: Culture and Customs of Nigeria, Westport 2000, p. 36.

- ↑ Alembi, Ezekiel: The Construction of the Abanyole Perceptions on Death through Oral Funeral Poetry, Ph.D Dissertation, University of Helsinki, Finland (2002), pp. 117-118, online: http://ethesis.helsinki.fi/julkaisut/hum/kultt/vk/alembi/theconst.pdf (retrieved: 20 December 2016).

- ↑ Alembi, Ezekiel: The Abanyole Dirge: ‘Escorting’ The Dead with Song and Dance, online: https://www.folklore.ee/folklore/vol38/alembi.pdf (retrieved 21 December 2016).

- ↑ van der Geest, Sjaak: Funerals for the Living: Conversations with Elderly People in Kwahu, Ghana, African Studies Review 43/3 (2000), pp. 103-129.

- ↑ Ray, Benjamin: The Story of Kintu: Myth, Death, and Ontology in Buganda, in: Karp, Ivan and Bird, Charles S. (eds.): Explorations in African Systems of Thought, Washington, DC 1980, p. 70.

- ↑ Owomoyela, Oyekan: Culture and Customs of Zimbabwe, Westport 2002, p. 33.

- ↑ Mbiti, Introduction 1975, p. 130.

- ↑ Reigel, Corey W.: The Last Great Safari: East Africa in World War I, Lanham 2015, p. 31.

- ↑ Page, Melvin E.: Black Men in a White Man’s War, in: Page, Melvin E. (ed.): Africa and the First World War, London 1987, p. 14; Strachan, The First World War in Africa 2004, p. 9.

- ↑ Page, Black Men 1987, p. 14.

- ↑ Strachan, The First World War in Africa 2004, p. 3.

- ↑ Hodges, Geoffrey: Kariokor: The Carrier Corps: The Story of the Military Labor Forces in the Conquest of German East Africa, 1914 to 1918, Nairobi 1999, p. 21.

- ↑ Lunn, Memoirs 1999, p. 215.

- ↑ Page, Melvin: The War of Thangata, in: Journal of African History (1978), pp. 90-97.

- ↑ The suffering, misery, and death of African servicemen in East Africa during the war has been ably captured by Hodges in his book Kariokor.

- ↑ A Senegalese war veteran quoted in Lunn, Memoirs 1999, p. 190.

- ↑ Page, Melvin: The Great War and Chewa Society in Malawi, in: Journal of Southern African Studies 6/2 (1980), pp. 171-182.

- ↑ There are several such cemeteries in France and French West Africa. The cemeteries in former British colonies are currently under the care of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). Chetty, Suryakanthie, Ginio, Ruth: Commemoration, Cult of the Fallen (Africa), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2015-06-17. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1546333/ie1418.10666 (retrieved: 15 August 2016).

Selected Bibliography

- Alembi, Ezekiel: The construction of the Abanyole perceptions on death through oral funeral poetry, thesis, Helsinki 2002: University of Helsinki.

- Alembi, Ezekiel: The Abanyole dirge. 'Escorting' the dead with song and dance, in: Folklore. Electronic Journal of Folklore 38, 2008, pp. 7-22.

- Birmingham, David; et al. (eds.): World War I and Africa, in: The Journal of African History 19/1, 1978.

- Echenberg, Myron J.: Colonial conscripts. The Tirailleurs Sénégalais in French West Africa, 1857-1960, Portsmouth; London 1991: Heinemann; J. Currey.

- Hodges, Geoffrey: Kariakor. The carrier corps. The story of the military labour forces in the conquest of German East Africa, 1914 to 1918, Nairobi 1999: Nairobi University Press.

- Kenyatta, Jomo: Facing Mount Kenya. The tribal life of the Gikuyu, New York 1962: Vintage Books.

- Killingray, David: Labour exploitation for military campaigns in British colonial Africa 1870-1945, in: Journal of Contemporary History 24/3, 1989, pp. 483-501.

- Lunn, Joe Harris: Memoirs of the maelstrom. A Senegalese oral history of the First World War, Portsmouth; Oxford; Cape Town 1999: Heinemann; J. Currey; D. Philip.

- Maxon, Robert: The years of the revolutionary advance, 1920-1929, in: Ochieng', William Robert (ed.): A modern history of Kenya, 1895-1980, Nairobi 1989: Evans Brothers, pp. 71-111.

- Miller, Charles: Battle for the Bundu. The First World War in East Africa, New York 1974: Macmillan.

- Ogot, Bethwell A.: History of the southern Luo, Nairobi 1967: East African Publishing House.

- Page, Melvin E. (ed.): Africa and the First World War, New York 1987: St. Martin's Press.

- Parsons, Timothy: The African rank-and-file. Social implications of colonial military service in the King's African Rifles, 1902-1964, Portsmouth 1999: Heinemann.

- Reigel, Corey W.: The last great safari. East Africa in World War I, Lanham 2015: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Smith, Robert Sydney: Warfare and diplomacy in pre-colonial West Africa, London 1976: Methuen.

- Strachan, Hew: The First World War in Africa, Oxford; New York 2004: Oxford University Press.