Origins and Early Career↑

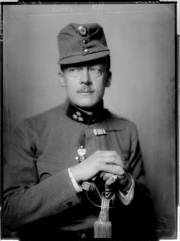

Graf Leopold Berchtold von und zu Ungarschitz (1863-1942) was born into a distinguished, extremely wealthy German-Moravian family with extensive land holdings in Bohemia, Hungary, and Lower Austria. His father, Sigmund Graf Berchtold (1834–1900) served in the Moravian Landtag and the Austrian Reichsrat; his maternal grandfather had been Habsburg ambassador to Prussia. Tutored at home, a customary practice for aristocratic children, he also completed a law degree. Fluent in Czech, Slovak, English, French and Italian, his competency in Magyar allowed him to address Hungarian politicians in their milieu.

In 1887, he began an administrative career in Moravia. In January 1893, he married Ferdinandine Gräfin Károlyi (1868-1955), daughter of a former ambassador to Berlin and London and heiress to extensive Hungarian lands.

Later, in 1893, Berchtold transferred to the Habsburg foreign ministry, initially working on Vatican and Albanian issues. In 1894, after passing an entry examination, he went to Paris as legation secretary. In 1897, Ambassador Alois Freiherr Lexa von Aehrenthal (1854-1912) wanted him to come to St. Petersburg, but he declined. Instead, he went to London as first secretary in the embassy. But Aehrenthal continued to press Berchtold to come to Russia; he did so in March 1903 and succeeded Aehrenthal as ambassador in 1906 when Aehrenthal became Habsburg foreign minister. Berchtold remained in St. Petersburg, the second most important embassy, until he retired in mid-1911 to return to Austria-Hungary.

Appointment as Foreign Minister and the Balkan Wars↑

Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916) appointed a reluctant Berchtold foreign minister on 17 February 1912, following the death of Aehrenthal. At forty-nine, he was the youngest foreign minister in Europe. As minister, he automatically became Francis Joseph’s principal adviser on foreign policy and war/peace decisions. The Thronfolger Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914) played no part in his appointment, though they were well acquainted and their wives were childhood friends.

In the first two years (1912 and 1913), Berchtold faced a series of interlocking issues that brought the monarchy to the edge of war with Serbia twice, Montenegro once, and Russia once. A more aggressive Russo-Serbian foreign policy in the Balkans led first to the creation of the secret Balkan League against the Ottoman Empire and the outbreak of the First Balkan War in October 1912. Russia kept thousands of extra troops on duty after their enlistments ended; Vienna responded with gradual troop increases along the Russian border and in Bosnia-Herzegovina to protect the Habsburg position.

The rapid Ottoman collapse threatened Habsburg interests but Berchtold exploited the London Conference to block Serbian access to the sea, helped by the creation of the new Albanian state. The return of General Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (1852-1925) as chief of staff in early December saw demands for a military showdown with Serbia and possibly with Russia. Berchtold, backed by Francis Joseph and with uncertain support from Germany, negotiated a reduction of tension, though war talk flared again in late April 1913 when Montenegro refused to abandon territory assigned to Albania.

The Second Balkan War (June-July 1913) saw Bulgaria’s defeat and new Habsburg friction with Serbia. In October, Vienna nearly went to war with Belgrade, this time over its failure to leave Albanian territory. But an abrupt seven-day ultimatum saw Serbia leave.

Then came the assassinations in Sarajevo on Sunday, 28 June 1914.

The Origins of the First World War↑

No person played a more important role in the start of the Great War than Berchtold. Had he counseled prudence and restraint, instead of war against Serbia, peace would almost certainly have been secured. By the late afternoon of Tuesday, 30 June, he had concluded that only a military showdown with Serbia would resolve the threat posed by Belgrade. He made this decision on his own, without any German pressure. Equally important, Francis Joseph also came to this conclusion, but only if Berlin and the Hungarian government headed by Premier István Tisza (1861-1918) gave full support.

Over the next two weeks, Berchtold worked adroitly to achieve these two goals. When Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) did not come to Vienna for the Archduke’s funeral for security reasons, Count Alexander Hoyos (1876-1937) was sent to Berlin to gain support. This maneuver prevented Tisza from trying to soften the approach. Berchtold’s ploy worked: the German leadership pledged support - the infamous “blank check” - for what they believed would be prompt military action against Serbia.

The second task, winning Tisza’s support, was far more difficult, disrupting all assumptions of quick action, for Tisza thwarted, objected, and pleaded for more time. Eventually, on 14 July, he agreed to action; Berchtold’s aides drafted a forty-eight hour ultimatum, designed to be unacceptable.

But Vienna, despite pressures from Berlin, delayed delivery of the note until the long scheduled French state visit to Russia ended on 23 July. The delivery of the ultimatum later that day immediately accelerated tensions. On 24 July, Russia started the process of recalling troops, before any other great power. Berchtold, who had hoped for no Russian intervention, did not counsel Francis Joseph to stop. Indeed, fearful of international intervention to block the war with Serbia, the foreign minister got the emperor and king to declare war against Serbia on 28 July. That night, shots were fired around Belgrade and the chance for peace was lost.

Later Career and the End of the Habsburg Monarchy↑

Berchtold remained foreign minister until 13 January 1915, finally leaving office after friction with Tisza over possible territorial concessions to keep Italy out of the war.

Berchtold soon went on active military duty, serving with the 16th Corps, which would be engaged in fighting on the Italian front. Then, on 23 March 1916, he became Obersthofmeister (Grand Court Master) to the Thronfolger Archduke Charles. In January 1917, after Francis Joseph’s death, Charles I, Emperor of Austria (1887-1922) appointed him Oberstkämmerer (Lord High Chamberlain) and Berchtold continued until the collapse of the monarchy, personally taking the crown jewels to Switzerland on 2 November as one of his final acts.

For four years after the war, Berchtold remained in Switzerland, finally returning home in 1923 to his beloved estate in Buchlau (Buchlov) in Moravia. During the next two decades, Berchtold worked on his memoirs (though they were never published), met with scholars, occasionally wrote pieces defending his decisions in July 1914, and managed his still considerable estate holdings. He died in Peresznye, Hungary, next to Austria’s current border, on 21 November 1942, and was buried in Buchlau.

Samuel R. Williamson, Jr., The University of the South

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Bridge, Francis Roy: The Habsburg monarchy among the great powers, 1815-1918, New York 1990: Berg et al..

- Clark, Christopher M.: The sleepwalkers. How Europe went to war in 1914, New York 2013: Harper.

- Hantsch, Hugo: Leopold Graf Berchtold. Grandseigneur und Staatsmann, 2 volumes, Graz 1963: Verlag Styria.

- Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914-1918, Vienna et al. 2013: Böhlau.

- Rauchensteiner, Manfried: The First World War and the end of the Habsburg monarchy, 1914-1918, Vienna 2014: Böhlau.

- Schmitt, Bernadotte Everly: Interviewing the authors of the War, Chicago 1930: Chicago Literary Club.

- Williamson, Jr., Samuel R.: Leopold Count Berchtold. The man who could have prevented the Great War, in: Bischof, Günter / Plasser, Fritz / Berger, Peter (eds.): From empire to republic. Post-World War I Austria, New Orleans et al. 2012: UNO Press; Innsbruck University Press, pp. 24-51.

- Williamson, Jr., Samuel R.: Austria-Hungary and the origins of the First World War, New York 1991: St. Martin's Press.