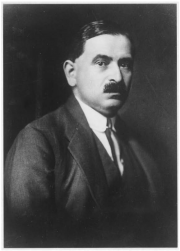

Leading Socialist Thinker↑

At the time of Austria-Hungary’s general mobilization in late July 1914, Otto Bauer (1881-1938) was already established as one of Austrian Social Democracy’s leading thinkers and politicians. Along with Karl Renner (1870-1950) and Victor Adler (1852-1918), he was one of the most prominent exponents of Austro-Marxism, an unorthodox school of Marxist thought based in early 20th century Vienna that famously sought to reconcile nationalism and theories of nationalism with socialism.

Already in 1907, at age twenty-six, Bauer published a monumental work on The Nationalities Question and Social Democracy. Bauer argued that nationalism – though responsible for fragmenting the Austrian workers’ movement along ethnic-national lines in the pre-war years – could, given the right legal-constitutional conditions, advance the cause of socialism because workers possessed a deep national consciousness that would not erode, as orthodox Marxists predicted, under the capitalist mode of production. In 1907 he also became secretary of the party’s newly formed parliamentary club, and joined the editorial boards of key Social Democratic periodicals – the Arbeiter-Zeitung and Der Kampf.

Participation in World War I↑

At the war’s beginning, Bauer authored an official party manifesto justifying the conflict as necessary to protect the central European proletariat against reactionary tsarist Russia. He thus fit into the mainstream of German-speaking central European socialists. He soon departed for the Russian front as a reserve officer (lieutenant) in the 3rd Regiment of the Tyrolian Kriegsjäger. Bauer distinguished himself as a courageous leader in a number of engagements and rose to company commander before being captured on 23 November 1914 by the Russians. From late 1914 to spring 1917 he was in a Russian internment camp in Siberia, cut off from news of the outside world but healthy enough to study Russian conditions and work on a philosophical manuscript that would appear in 1924 as Das Weltbild des Kapitalismus.

Bauer’s Release and Later Work↑

The Russian Revolution captivated Bauer intellectually and opened possibilities for his return to Austria. Victor Adler mobilized prominent socialists among the Entente Powers to negotiate with the provisional government in Petrograd for Bauer’s transfer there from Siberia. After some weeks in Petrograd, Bauer returned in September 1917 to Vienna. Still officially a military officer and employed as an economist in the war ministry, Bauer began publishing on the Russian Revolution under the pseudonyms Heinrich Weber and Karl Mann.

Although he joined the Social Democratic Leftist anti-war opposition upon his return and was widely regarded as a radical, even a Bolshevik, Bauer remained ambivalent about the Russian Revolution’s prospects through the end of the war. In his view, the agrarian backwardness of Russian society precluded real socialism from emerging there, instead viewing bourgeois democracy as the likelier outcome. Nonetheless, he recognized that the revolution had ushered in a new phase in the East-Central European Slavic nationalist movements and, further, that Austria-Hungary could not survive the war.

By opposing the Burgfrieden policy of most Social Democratic leaders and urging them to think about a Central European future without multinational empires, Bauer espoused more radical views than many of his peers in 1917-18. Yet because he did not condone the spontaneous mass protests that surfaced in the final war years, Austrian authorities – who knew of his pseudonyms – allowed him to work virtually unfettered. In autumn 1918, Bauer played a central role in the establishment of the Austrian Republic, serving as foreign minister after Adler’s death and propagating Anschluss with Germany.

Jakub Beneš, University of Birmingham

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Bauer, Otto: The question of nationalities and social democracy, Minneapolis 2000: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hanisch, Ernst: Der grosse Illusionist. Otto Bauer (1881-1938), Vienna 2011: Böhlau.

- Kulemann, Peter: Am Beispiel des Austromarxismus. Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterbewegung in Österreich von Hainfeld bis zur Dollfuss-Diktatur, Hamburg 1979: Junius.

- Löw, Raimund: Otto Bauer und die russische Revolution, Vienna 1980: Europa-Verlag.