Introduction↑

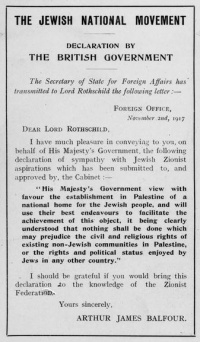

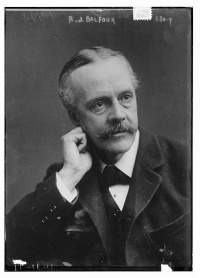

The Balfour Declaration, issued on 2 November 1917, is one of the most influential documents leading to the establishment of the state of Israel. The text itself is only a paragraph long, part of a letter from Great Britain’s Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour (1848-1930) to Lord Walter Lionel Rothschild (1868-1937). It was the product of behind-the-scenes wordsmithing and political maneuvering; finalized on 31 October 1917 and publicly issued on 2 November 1917, reading:

Key to understanding the Balfour Declaration’s power is its creators’ word choices. The passage “a national home for the Jewish people”, coupled with the protection of “civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine” and “the rights and political status of Jews in any other country” rank among the most powerful and simultaneously ambiguous phrases in diplomatic history.

Under Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928), the British government had not expended much energy grappling with questions of Zionism and a future Jewish home in Palestine. However, as the war worsened, the Asquith government fell in late 1916. David Lloyd George (1863-1945), who had a sympathetic ear for Zionist organizations, became prime minister. But why, ultimately, did the British end up issuing the declaration, when other states (like Germany) were on the verge of doing so, or at the very least contemplating it? There is no one answer. For some, like Lloyd George, supporting Zionist efforts was both politically expedient and morally good.

The Politics of Christian Zionism↑

Morally, for many devout Christians, particularly Protestant evangelical denominations (e.g. Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians), Zionism contained a messianic angle. Returning the world’s Jews to Palestine could bring about Christ’s second coming; at the very least it righted millennia of anti-Semitic wrongs. Christian Zionism can be easily overstated as a rationale for the Declaration’s issuance, however, and is only one of the factors that led politicians to consider a pro-Zionist statement.

Political Zionism↑

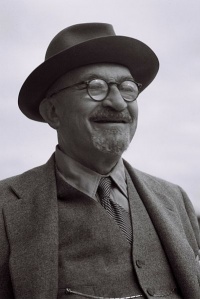

Politically, there is much more to build on. The increasingly frustrating war effort demanded that anything that might end the war, whatever it may be, should be tried. On 13 June 1917, Chaim Weizmann (1874-1952) wrote to Foreign Office Assistant Under-Secretary Sir Ronald Graham (1870-1949) that “it appears desirable from every point of view that the British Government should give expression to its sympathy and support of the Zionist claims on Palestine.”[1] That same day, Graham pointed out to Cabinet members the need for an Allied effort “to secure all the political advantages we can out of our connection with Zionism,” further noting the possibilities it held for “reaching the Jewish proletariat” in Russia.[2] The propaganda qualities Zionism appeared to offer garnered support among officials who might not have been swayed by purely ideological considerations. In the United States, perceptions among non-Jewish leaders, particularly old anti-Semitic tropes like those suggesting strong Jewish ties to finance and industry, further fed a general push for pro-Zionist statements. Propelled, at least in part by the “tribal” quality ascribed by non-Jews to Jewish populations, the British government established a “Jewish Legion” in 1917 (ultimately only the 38th, 39th, and 40th Royal Fusiliers, known as “the Judaeans”) and issued military recruitment campaigns across the Empire almost simultaneously with the Declaration’s issuance.

The Declaration, however much desired or detested by British officials, was not ultimately their idea. Jewish leaders had long contemplated a return to Israel and reestablishment of a Jewish state. They envisioned a state defined by political dimensions, however, not simply one based on religious or philanthropic concerns. This concept emerged in the late 19th century, first voiced by thinkers like Leo Pinsker (1821-1891) in Auto-Emancipation (1882) and Theodor Herzl (1860-1904) in The Jewish State (1896). Such works laid the foundation for Zionist organizations like the World Zionist Organization and inspired the activists who worked with British officials on the Balfour Declaration.

Nahum Sokolow (1859-1936), a Zionist diplomat in London, and Chaim Weizmann, head of the English Zionist Federation, are credited with leading the Jewish pro-Zionist efforts to bring about the Declaration. Weizmann, who came to Great Britain in 1904 and worked in the University of Manchester chemistry department, leveraged his scientific advancements in relationships among the British press and politics. Friends with Charles Prestwich Scott (1846-1932) of the Manchester Guardian and acquainted with Sir Mark Sykes (1879-1919), Weizmann and his allies shifted public sentiment in favour of a declaration supporting a Jewish national home in Palestine. No single propagandistic device worked to secure the declaration, but in tandem they worked as a means to the end.

Drafting the Declaration↑

While earlier versions had been under discussion since spring 1917, political Zionists formally presented their goals in the Preliminary Zionist Draft on 12 July 1917. Authored by Sokolow, the statement forcefully reasserted the concepts of Palestine as the “National Home of the Jewish people,” but nowhere mentioned populations already living in the region. Calls for “internal autonomy” and substantial political power for the Jewish National Colonizing Corporation made up the heart of the Preliminary Zionist Draft. In subsequent drafts, collaboration between Zionist officials and the British government was increasingly stressed, while discussion of non-Zionist constituents in Palestine continued to be neglected. The significance of every word was certainly understood. At one point in the review process the document was given to U.S. officials for their input. President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) saw it twice and Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis (1856-1941) argued against using the word “race”, advocating instead for “people” as being both less aggressive and more practical.

Even as the wording was hashed out over the scope of the Zionist agenda, the native Palestinian population remained largely lost. This changed in August 1917 when the newly appointed secretary of state for India, Edwin Montagu (1879-1924) reintroduced the topic of the Palestinians and other constituencies. Montagu, who also happened to be a Jewish anti-Zionist, was keenly aware of the statement the British government would be making should it issue a declaration like the Preliminary Zionist Draft. He contextualized political Zionism in a broader global framework than did most of his Cabinet counterparts. For him, for the government to espouse political Zionism as an admirable and defensible nationalist sentiment, was inherently hypocritical when at the same time that same government jailed Irish and Indian nationalists for championing a similar ideology. Other anti-Zionists across Europe, North America, and the Middle East shared Montagu’s sentiment and advocated against fundamentally establishing a Zionist state in Palestine.

Montagu’s advocacy for tighter wording in any potential declaration was ultimately successful in at least establishing the rights of Jews outside of Palestine and acknowledging the existence of Palestine’s non-Jewish inhabitants. The 4 October Milner-Amery Draft read:

The Milner-Amery Draft highlighted both the rights and status of Palestine’s non-Jewish communities and the future status of Jewish communities not wanting to move to a Palestinian “national home”. However, the introduction of race in discussing the world’s Jewry further problematized the nature of dialogue about national identity not only vis à vis Zionism but with regard to other nationalist movements as well. “Race” was, in the end, removed from the text and the component of non-Zionist populations remained, but as was evident from Montagu’s reaction to the Balfour Declaration’s release, it was not immediately embraced by all.

In Palestine, the Balfour Declaration’s issuance, and indeed its incorporation into the Mandate for Palestine, firmly established Zionism while destabilizing the non-Zionist population (whether it be Jewish, Christian, or Muslim) in the region. What “a national home for the Jewish people” meant in 1917 was just as unclear as it was in 2017. A year after the Declaration’s final release in a letter to Balfour, Curzon raised objections to the creation of a Jewish state. He noted Chaim Weizmann’s call for “the ‘whole administration of Palestine’ being so constituted as to make a Jewish Commonwealth under British trusteeship,” and that “a Commonwealth as defined in every dictionary is a ‘body politic,’ a ‘state’.”[4] Continuing, Curzon stated, “I feel tolerably sure therefore that Weizmann may say one thing to you or while you may mean one thing by a National Home, he is out for something quite different. He contemplates a Jewish State.”[5] In a similar vein, General Edmund Allenby (1861-1936), who had initially been sympathetic to the Zionist enterprise, by 1919 began to question the price of destabilization it was bringing to the region. Even among the framers of the Balfour Declaration there remained a great deal of ambiguity about what the Declaration ultimately meant and entailed.

Maryanne A. Rhett, Monmouth University

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Notes

- ↑ Weizmann, Chaim: Trial and Error. The Autobiography of Chaim Weizmann, volume one, Philadelphia 1949, p. 203.

- ↑ Graham, Minute R.: 13 June 1917, PRO FO 371/3058, in: Brazilay-Yegar, Devorah: Crisis as Turning Point. Weizmann in World War I, in: Studies in Zionism 6 (1982), p. 252.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 31.

- ↑ Fisher, John: Curzon and British Imperialism in the Middle East 1916-19, London 1999, p. 214.

- ↑ Ibid.

Selected Bibliography

- Fisher, John: Curzon and British imperialism in the Middle East, 1916-19, London; Portland 1999: Frank Cass.

- Gelvin, James L.: The modern Middle East. A history, New York 2005: Oxford University Press.

- Reinharz, Jehuda: The Balfour Declaration and its maker. A reassessment, in: The Journal of Modern History 64/3, 1992, pp. 455-499.

- Renton, James: The Zionist masquerade. The birth of the Anglo-Zionist alliance 1914-1918, New York 2007: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rhett, Maryanne A.: The global history of the Balfour Declaration. Declared nation, New York 2016: Routledge.

- Stein, Leonard: The Balfour Declaration, New York 1961: Simon and Schuster.

- Vereté, Mayir: The Balfour Declaration and its makers, in: Middle Eastern Studies 6/1, 1970, pp. 48-76.