From Doctor to Socialist↑

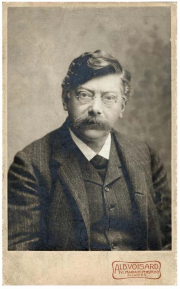

Dr. Victor Adler (1852-1918) entered the First World War in a state of ill health and deep apprehension. Hailing from a prosperous Prague Jewish merchant family, he had, as student of medicine in Vienna, joined the German nationalist movement under Georg von Schönerer’s (1842-1921) leadership before leaving due to the movement’s rising anti-Semitism. After a brief career as a physician helping Vienna’s poor, he devoted himself completely to the Austrian workers’ movement. In the 1880s, he unified the estranged factions of Austrian Social Democracy and did most to define its course in the years 1890-1918, struggling throughout against rising ethnic-national tensions among workers. An unorthodox Austro-Marxist like Otto Bauer (1881-1938) and Karl Renner (1870-1950), Adler believed that nationalism and theories of nationalism could somehow be reconciled with socialism.

Pro-war Sentiments↑

On 27 July 1914, he appeared, exhausted and feeble, at an emergency meeting of the Second Socialist International in Brussels to give the keynote address. Capturing the sentiments of many present, Adler dejectedly admitted that his party could do nothing more to stop the war. Yet despite his desolate attitude, Adler was convinced that Austria-Hungary was engaged in a defensive struggle against Russian expansionism and he defended the pro-war attitudes of other leading Austrian socialists against attacks from the crystallizing leftist opposition, which included his son Friedrich Adler (1879-1960). Indeed, throughout the war, even as he became a vocal critic of the regime’s repressive policies and insincere peace overtures, the elder Adler maintained the position that “worse than war is defeat in war.”[1] He thus set the tone for Austrian Social Democracy’s “activist” compliance with the imperial war effort and, along with the majority of party leaders, worked to discourage workers’ growing anti-regime radicalism.

A Difficult Father-Son Relationship↑

This position infuriated his son Friedrich, with whom he had a tumultuous, if affectionate, relationship. Friedrich, despairing of his own and the leftist opposition’s marginalization, took matters into his own hands in autumn 1916, shooting Minister-President Count Karl Stürgkh (1859-1916) dead in a Viennese restaurant to protest the regime’s war effort and Social Democracy’s impotence. Victor Adler distanced the party from his son’s act but also from popular speculation about Friedrich’s mental state. At the trial in May 1917, the father gave an impassioned and sympathetic witness testimony for the defense. Though sentenced to death, Friedrich was not executed and sat in prison until the war’s end, when he was amnestied. He benefited from the more clement judicial system under Charles I, Emperor of Austria (1887-1922), which in 1917 amnestied political prisoners such as the Czech nationalist leader Karel Kramář (1860-1937), and avoided the brutal – and for Austria’s image, disastrous – summary executions that claimed the lives of men like Cesare Battisti (1875-1916) in the first years of the war.

Final Months↑

Victor Adler welcomed both phases of the Russian Revolution but considered the Bolshevik approach wholly unsuited to Austrian conditions. In January 1918, he exhorted strikers in Lower Austria and Vienna to return to work, admonishing their stubborn adherence to unrealistic demands. Characteristically, he feared bloodshed if the striking workers were to defy armed state power for too long. In October 1918, as his health worsened further, Victor Adler finally accepted his protégé Otto Bauer’s prediction that the empire could not survive and was, on 30 October 1918, elected foreign minister of German Austria by the provisional national assembly. He served in this role for exactly eleven days, during which time he oversaw the end of Austrian hostilities with the Entente and witnessed Friedrich’s release. He died on 11 November 1918.

Jakub Beneš, University of Birmingham

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Notes

- ↑ Meysels, Lucian O.: Victor Adler. Die Biographie, Vienna 1997, p. 208.

Selected Bibliography

- Maderthaner, Wolfgang, Beniston, Judith; Vilain, Robert (eds.): Austro-marxism. Mass culture and anticipatory socialism, in: Austrian Studies 14, 2006, pp. 21-36.

- Maderthaner, Wolfgang: Victor Adler und die Politik der Symbole. Zum Entwurf einer 'poetischen Politik', in: Leser, Norbert / Wagner, Manfred (eds.): Österreichs politische Symbole. Historisch, ästhetisch und ideologiekritisch beleuchtet, Vienna 1994: Böhlau.

- Meysels, Lucian O.: Victor Adler. Die Biographie, Vienna 1997: Amalthea.

- Mommsen, Hans: Die Sozialdemokratie und die Nationalitätenfrage im habsburgischen Vielvölkerstaat, Vienna 1963: Europa-Verlag.