Introduction↑

Women in Russia were mobilized for war beginning in 1914 in a vast array of activities essential to the war effort, resulting in the participation of millions both on the home front and on the frontlines. They contributed in ways that were consistent with past wartime experiences, as well as in new and unique ones. The participation of women in Russia during the First World War transcended previous war experiences, created new opportunities and challenges, and blurred boundaries of gendered behavior and expectations. Even when they participated in conventionally acceptable roles, for example as nurses, they often did so in places and activities that crossed gender borders, on the front and in the direct line of fire. Their experiences often differed from those of their Western counterparts as a result of the highly mobile nature of warfare on the Eastern Front and their close proximity to the fighting. They also served in distinctly unconventional ways, as thousands became soldiers, greatly outnumbering the handful of examples of female soldiers in other warring states, and uniquely, as part of state-sponsored all-women’s military units. Furthermore, the activities of Russian women in this war set important precedents for their use in future military conflicts.

Despite their vital contributions, Russian women’s participation in the First World War, while recently receiving increased attention from scholars, is still understudied both in comparison to male experiences and to that of women in Western belligerents.[1] Although some focused studies have been produced, examining aspects of women’s wartime participation such as nursing, which had become a culturally acceptable means of female involvement in the war effort,[2] and, as a result of its extraordinary nature, women’s soldiering, there is as yet no comprehensive history of Russian women’s wartime experiences.[3] This is the result of a combination of factors: the privileging of male actors in war historiography generally, the geographic and cultural “othering” of Russia that has led to its neglect in Western scholarship, and the overshadowing of the war by the events of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and subsequent Soviet dismissal of the First World War as a “bourgeois imperialist” conflict unworthy of serious study.[4]

Drawing on archival sources, as well as the writings of women themselves and those who observed them contemporaneously, this article examines women’s mobilization first in the wartime labor force, followed by medical service, and lastly, in military action. Such an examination is important not only in providing a fuller understanding of the war, but also because the experiences of Russian women were often exceptional, even while they share some more universal attributes of war experience.

Women in the Labor Force↑

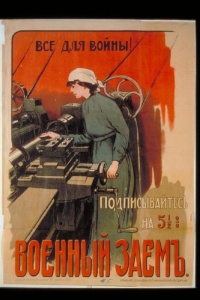

The military call-up of 15 million men caused a labor shortage that necessitated a massive increase of women in the workforce. To accommodate demand, the Russian government relaxed restrictions on female and child labor. Women’s numbers in urban industries increased to nearly 45 percent of the labor force and they rose significantly in male-dominated areas, such as metalwork, machine manufacturing, and munitions production. They filled in for conscripted men, becoming streetcar conductors, truck drivers, and railway workers. They moved into utilities, accountancy, telegraph operation, and secretarial work. Thousands took on jobs as messengers, mechanics, chimney sweeps, mail carriers, police officers, janitors, and carters. Despite the urgent need for their labor and the vital contributions they made to the war effort, women workers continued to be underpaid, earning as little as 35 percent of male wages. Some were critical of their participation in such endeavors, seeing women as threats to male preeminence.[5]

The largest increase of female labor occurred in agriculture. By 1916, an estimated 72 percent of workers on peasant farms were women, with an additional 58 percent serving on landowner estates. Similar to the response to women’s increased presence in urban labor, the reaction to the “feminization” of agricultural labor was sometimes negative, as some perceived this as challenging male control.[6]

As a result of the war, women encountered newfound freedoms and faced serious challenges. The absence of male authority figures meant less restriction and more ability to control their personal lives for some. Women migrated to new areas seeking employment and encountered new opportunities.[7] However, the war caused significant shortages of necessities and sharp inflation, which had profoundly negative effects on women and their families. The intrusion of the war into civilian spaces transformed large swaths of settled areas in the western regions of the empire into zones of military operation, precipitating tremendous economic and social upheavals and a massive refugee crisis. The majority of the newly homeless were women and children, who often came to rely on relief organizations. Some women engaged in sex work when other employment was unavailable or insufficient to provide enough financial support.[8] Others mobilized to express their discontent in vocal, sometimes violent ways as unrest materialized into bread riots and other forms of protest over the course of the war.[9] Soldiers’ wives organized demonstrations and unionized.[10] The most salient incidence of women’s discontent fomented in Petrograd in February/March 1917 and led to mass demonstrations against the war and tsarist regime that eventually brought the empire to collapse.

Women’s War Work↑

Insufficiently prepared for a conflict of this scale, the tsarist government was forced to rely on civilians to provide auxiliary support, despite its deep mistrust of civil society. Swept up in the initial outpouring of patriotic sentiment, many women lent their assistance to the war effort. Contemporary women’s periodicals appealed to readers to serve the nation.[11] Response to such calls came primarily from middle- and upper-class women and members of the intelligentsia, who secured provisions, sewed linens and warm clothing, made care packages, and staffed travelers’ aid stations for soldiers. Others from Russia’s working classes carried out auxiliary services for the Russian military as trench diggers, railroad workers, laundresses, military drivers, and clerical workers.

Women offered their services not only to assist the troops, but also to feed, clothe, and shelter civilians negatively affected by the dislocations of war. They worked in soup kitchens, mobile aid stations, shelters, orphanages, and other facilities. Women’s organizations and groups such as the Mutual Philanthropic Society and the League for Women’s Equality dedicated themselves to assisting in the war effort, recruiting women from all over the empire. Feminists who had long pressed for increased rights and opportunities embraced wartime service as a means to demonstrate women’s usefulness and responsibility as citizens. They hoped their dedication would be rewarded politically and legally.[12]

Wartime Nursing↑

The most popular form of women’s wartime service was nursing, which was seen as an appropriate means for women to contribute to the war effort. Russia’s wartime nurses of the First World War, known as “sisters of mercy,” numbered over 31,000. They hailed from every social class, but the majority was from the educated elite since fundamental literacy was a requirement of enlistment. The severe shortage of trained nurses led to shortening training from one year to two months, and when even this failed to meet demand, further reduction to six weeks. As a result, many wartime nurses had little more than cursory medical knowledge.

Once in service, wartime nurses faced challenging circumstances. Unlike their Western counterparts, many of Russia’s sisters of mercy served very close to the fighting. Due to the highly mobile nature of the conflict on the Eastern Front, where the frontlines shifted rapidly and often, as contrasted with the largely stagnant trench warfare in the west, medical units often had to move quickly to keep up with the troops they treated. Official regulations restricting female personnel from working close to the battlefields proved impossible to uphold. As a result, Russian nurses often served in forward positions and thus were exposed to dangers similar to those experienced by soldiers: artillery and gun fire, bombardment, flying shrapnel, and gas attacks. Like soldiers, they experienced extremes of cold, heat, dampness, insect infestation, and illness. Psychologically, Russian nurses also suffered from fear, paralysis, “shell shock,” and other emotional traumas associated with mechanized warfare.[13]

While conventional wisdom held wartime nursing as appropriate for women as a result of its association with caring and nurturing, nurses often found it easier to shed more traditionally “feminine” attributes and adopt more “masculine” ones, both mentally and physically. As a result of the lack of sufficient resources, high death rate, and speed with which they had to treat patients, nurses often had to suppress their emotions. The standard uniform of the sister of mercy (usually a long woolen dress or skirt with blouse and apron, veil to cover the hair, and women’s shoes) was impractical in conditions of mud, rain, snow, and extreme heat and cold. Nurses at the front often exchanged their uniforms for men’s boots, leather jackets, and even trousers. Cosmetics and even items of basic hygiene were impractical and often abandoned.

Although many lauded nurses for their efforts, as attested by extensive positive coverage in contemporary periodicals, some voices expressed criticism. These included concerns about removing women from the domestic realm and exposing them to the dangers and deprivations of war. Others worried those left behind, particularly children, might lack sufficient care. Still others believed that some women entering medical services became sisters of mercy only because it was “fashionable.” Indeed, many of the women of the Russian elite, including the Tsarina Aleksandra (1872-1918) and her two eldest daughters, members of the aristocracy, and celebrities entered the nursing service. Their motives were sometimes doubted as less than altruistic and instead seen as self-aggrandizing. Some even accused wartime nurses of sexual impropriety, including prostitution. As a result, they earned the disparaging moniker of “sisters of comfort.”[14]

Despite these criticisms, it is clear that the Russian military machine would have been unable to operate effectively without the contributions of the thousands of female nurses, as its own military medical services were woefully inadequate and unprepared for total war. This was not just a result of the massive casualties sustained, but also because of the virulent spread of epidemic diseases.[15] Nurses also cared for the thousands of civilian victims that became collateral damage of mechanized warfare and the public health crises that the war precipitated.

Women Soldiers↑

Not all Russian women were satisfied with more “traditional” roles: many desired to fight on the front lines. Although the phenomenon of the female soldier was not new, in Russia during the First World War, not only did their numbers exceed previous examples, but, in 1917, they were part of an unprecedented social experiment: the organization of all-female combat units.

Between the outbreak of war in August 1914 and the February Revolution in 1917, individual women integrated into existing military units. They did so in two ways: disguising themselves as men or obtaining permission from officials that allowed them to circumvent Russian imperial law. Male guise largely succeeded as a result of the imperial army’s rather unsystematic implementation of medical examinations and is indicative of a failure of centralized control. Women could avoid scrutiny by joining a unit in transit to or already located at the front, rather than at official initial intake points. Other times, women could find sponsorship from a sympathetic male relative, friend, soldier, or officer. There were those who took their requests to the highest levels, even to the tsar himself.[16]

Once enlisted, these women demonstrated their abilities as combatants. Indeed, a number outperformed men, often putting themselves at greater risk, likely in an effort to avoid suspicion. Perhaps even more important was the fact that all the women were volunteers with strong desires to serve. This stood in contrast to many male troops, who accepted conscription with “sullen resignation.”[17]

A definitive count of the number of these women soldiers is not possible, since many became known only if wounded and examined by medical personnel. Many likely served without being discovered, retaining their male personas. Much of the information available about women soldiers comes from the contemporary media, both domestic and foreign, which often portrayed them as examples of patriotic devotion in sensationalized, decidedly pro-war, rather than objective, accounts. Others were unconvinced that such action was appropriate for women, based on essentialist understandings of gender that centered on caring and nurturing and displayed considerable ambivalence, even hostility, to the idea of women participating in killing and therefore downplayed their efforts and minimized their numbers.

The pattern of individual, mostly disguised, women enlisting in male units gave way to the systematic organization of all-female military units in the spring and summer of 1917. This was an unprecedented event in the history of modern warfare. The phenomenon is well-documented in archival records tracking the creation of these units, as well as in a few memoirs of women who participated in them.[18] While some of the information included in personal accounts is not corroborated by other sources, much of it is reflected in the documentary record of the main administration of the Russian army’s general staff.

Two primary factors led to the creation of all-female units: first, the weakening condition of the Russian army and the accompanying efforts to prepare it for one last offensive and, second, public pressure by women to expand their roles in the war, with the hopes this would lead to greater rights and opportunities.

The first is the result of the state of the Russian army in spring 1917, which was one of considerable deterioration as a result of widespread desertion, fraternization, and insubordination. Such problems were the result of war-weariness, high casualties, heightened awareness of civilian suffering, as well as anti-war agitation. Many soldiers did not want to continue fighting and few were willing to undertake a new offensive. Military discipline was increasingly difficult to enforce after the dissemination of Order No. 1, which outlawed the use of corporal punishment on insubordinate soldiers and permitted the formation of soldiers’ committees, giving soldiers control over the weapons and orders of their units.

Despite these problems, the new Provisional Government was committed to undertaking the offensive. In an attempt to shore up morale and battle-readiness, Russian authorities decided to create new types of military units comprised of enthusiastic volunteers, including women. These “revolutionary,” “shock,” and “death” battalions would be comprised of the most enthusiastic volunteers, those willing to be the first into battle and serve as examples to faltering troops. The idea was that these units would have the effect of inspiring regular troops by demonstrating their willingness to sacrifice themselves for the homeland. This was coupled with the notion that sending women to the front would shame men into returning to their duty as defenders of the nation.[19]

Minister of War and soon-to-be Prime Minister Alexander Kerensky (1881-1970) authorized decorated veteran soldier Maria Bochkareva (1889-1920) to organize the 1st Russian Women’s Battalion of Death in May 1917. Initially, the unit attracted several thousand women. But as a result of Bochkareva’s strict discipline, her rejection of the rights afforded soldiers by Order No. 1, and zero tolerance for any hint of “femininity” (requiring the recruits to shave their heads, give up personal hygiene items – even toothbrushes – and encouraging them to spit and swear), the unit faced mass attrition. The 300 remaining women began intensive, month-long training before they were sent to participate in the June Offensive.

A number of other women pressured the Provisional Government to allow female enlistment in the armed forces.[20] As a result, fourteen other all-female military units were authorized in the summer of 1917. A second unit was organized in the capital, the 1st Petrograd Women’s Battalion, along with two communications detachments. Many of those weeded out by Bochkareva’s draconian policies entered this new unit, which eventually consisted of approximately 1,500 women. In Moscow, the 2nd Moscow Women’s Battalion of Death and two communications detachments were formed.[21] The 3rd Kuban Women’s Shock Battalion was formed in Ekaterinodar. Additionally, five communications detachments were established in Kiev, along with two more such units in Saratov. These units were organized and trained by the local military commands and staffed by male officers until such time as sufficient numbers of trained women officers could replace them. Twenty-five women enrolled in the Aleksandrov Military Academy in Moscow for this purpose.[22]

Official efforts to increase the numbers of women’s units did not satisfy public demand and the movement grew, with formations arising in ten additional cities around the empire. Such efforts were often the work of progressive women’s groups seeking to demonstrate women’s value as citizens with the hope of political rewards.[23] In August, the Petrograd Women’s Military Union held a Women’s Military Congress, which pushed for further integration of women into the Russian military and the establishment of standardized rights and benefits for women soldiers and veterans.

These grassroots efforts were not sanctioned by the Russian government and in fact caused it considerable concern, as it had no control over them. Moreover, military authorities were skeptical about the usefulness of such units. Statistically, they would make little difference, numbering approximately 5,000 in an army of millions. Their value was thus largely understood as propagandistic and this is well-documented by both the ways in which military authorities spoke about them and the extensive press coverage they received in both the Russian and foreign media. Some questioned whether women would be able to endure the rigors of combat. Others worried about male reactions. It is important to note that, although they initially faced unwanted sexual advances and hostility from male soldiers, when tested, the members of Bochkareva’s battalion proved themselves capable soldiers, as the individual women soldiers who had fought in male units had similarly demonstrated. They carried out an attack on 9 July 1917 near the town of Smorgon (in present-day Belarus), being the first to charge when men hesitated. They advanced to the third line of German trenches and even inspired many of the men to join them. But the attack proved unsustainable, particularly once male soldiers discovered stores of alcohol left behind by the enemy and began to imbibe. The Germans counter-attacked and drove Russian forces back, nullifying most of the advance. Despite this, the women soldiers performed their duties well and were uniformly lauded by command personnel who witnessed their actions first-hand.[24] They also managed to capture nearly 200 German prisoners of war.[25]

The June Offensive proved to be a failure, however, and the Russian army continued its deterioration. In the end, the presence of dedicated women soldiers did little to stem this decline. In fact, many male soldiers grew increasingly hostile to them. By September, the Russian military command saw little reason to continue funding and training them and began to withdraw its support. The movement was ended by the new Bolshevik leadership, which ordered the women’s military units disbanded. Although not ideologically opposed to women in combat, they saw these units as “dupes” of the Provisional Government they had just overturned, particularly because a small company of the 1st Petrograd Women’s Battalion had participated in the defense of the Winter Palace against the Bolsheviks.[26] Some women returned to civilian life, but others went on to fight on both sides of the conflict during the ensuing Civil War.

Conclusion↑

The mobilization of Russian women during the Great War clearly exposes the limitations of the notion of war as a distinctly male experience, demonstrating the extent to which the empire was heavily dependent on women, while also indicating that the “borderlines” of masculinity and femininity, of appropriate gender roles and behaviors, experienced “mutations” during the war.[27] Women’s actions also simultaneously obscured the separation between gendered conceptions of public and private spheres.

Despite challenges that chipped away at traditional gender ideology, long-standing notions of gender and their application in wartime were not completely disrupted and, indeed, remained influential in the post-war period. Although the women’s military movement was not successful in integrating women into the Soviet or post-Soviet armed forces on a permanent basis, the creation of all-female units in the First World War set the precedent for employing women in combat during times of exigency. This would be the policy adopted by the Bolsheviks in the Civil War, in which 20,000 women served, as well as in the Second World War when approximately 395,000 women were allowed to fight and another roughly 600,000 served in auxiliary capacities at the front. Here again, accusations of sexual impropriety would plague women, wherein Red Army nurses serving during the Second World War earned the derogatory epithet of “mobile field wives.” Nevertheless, it would be impossible to wage war without the contributions of women. Women continued to find ways to move beyond traditional confines and find places in the public sphere and contribute to national interests.

Laurie Stoff, Arizona State University

Section Editor: Nikolaus Katzer

Notes

- ↑ For example, see Gatrell, Peter: The Epic and the Domestic. Women and War in Russia, 1914-1917, in: Braybon, Gail (ed.): Evidence, History and the Great War. Historians and the Impact of 1914-1918, New York 2003, pp. 198-215; Meyer, Alfred: The Impact of World War I on Russian Women’s Lives, in: Clements, Barbara / Engel, Barbara / Worobec, Christine (eds.): Russia’s Women. Accommodation, Resistance, Transformation, Berkeley 1991, pp. 208-224.

- ↑ For example, see Beliakova, N. A.: Sestry miloserdiia Rossii (Russia's Sisters of Mercy), St. Petersburg 2005; Posternak, A. V.: Ocherki po istorii obshchin sestry miloserdiia (Essays on the history of Sister of Mercy Communities), Moscow 2001; Romaniuk, V. P. / Lapotnikov, V. A. / Nakatis, Ia. A.: Istoriia sestrinskogo dela v Rossii, St. Petersburg 1998; and Stoff, Laurie S.: Russia’s Sisters of Mercy and the Great War. More than Binding Men’s Wounds, Lawrence 2015.

- ↑ For example, see Drokov, Sergei: Organizator zhenskogo batal’on smerti (The Organizer of the Women's Battalion of Death), in: Voprosy Istorii (Problems of History) 7 (1993), pp. 164-169; Griese, Ann Eliot / Stites, Richard: Russia. Revolution and War, in: Goldman, Nancy Loring (ed.): Female Soldiers. Combatants or Noncombatants? Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, Westport 1982, pp. 61-84; Ivanova, Iu. N.: Khrabreishie iz prekrasnykh. Zhenshchiny Rossii v voinakh (The Bravest of the Beautiful: Women of Russia in War), Moscow 2002; Senin, A. S.: Zhenskie batal’ony i voennye komandy v 1917 godu (Women's Battalions and Military Units in 1917), in: Voprosy istorii (Problems of History) 10 (1987), pp. 176-182; Stockdale, Melissa: My Death for the Motherland is Happiness. Women, Patriotism, and Soldiering in Russia’s Great War, 1914-1917, in: American Historical Review 109 (2004), pp. 78-116; Shcherbinin, P. P.: Voennyi factor v povsednevnoi zhizni russkoi zhenshchiny v XVIII – nachale XX v. (The Military Factor in the Everyday Lives of Russian Women from the 18th to the Beginning of the 20th Centuries), Tambov 2004; and Stoff, Laurie S.: They Fought for the Motherland. Russia’s Women Soldiers in World War I and the Revolution, Lawrence 2006.

- ↑ Recently, both Russian and Western scholars have produced a number of important works on Russia’s Great War that redress such neglect.

- ↑ Meyer, The Impact of World War I 1991, pp. 213-214.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 214-216.

- ↑ Bulgakova, Liudmila: The Phenomenon of the Liberated Soldier’s Wife, in: Lindenmeyr, Adele / Read, Christopher / Waldron, Peter (eds.): Russia’s Home Front in War and Revolution, 1914-22. The Experience of War and Revolution, volume 2, Bloomington 2016, pp. 301-326.

- ↑ Gatrell, Peter: A Whole Empire Walking. Refugees in Russia during World War I, Bloomington 1999, pp. 115-126.

- ↑ Engel, Barbara Alpern: Not by Bread Alone. Subsistence Riots in Russia during World War I, in: The Journal of Modern History 69/4 (1997), pp. 696-721.

- ↑ Badcock, Sarah: Women, Protest and Revolution. Soldiers’ Wives in Russia During 1917, in: International Journal of Social History 1 (2004), pp. 47-70.

- ↑ See issues of Damskii mir (Ladies’ World), Zhenskoe delo (Women’s Affairs), Zhenskii vestnik (Women’s Chronicle) and other Russian women’s journals beginning in September 1914 and continuing through the war and Iakovleva, A. K.: Prizyv k Zhenshchinam (“Call to Women"), in: Zhenshchina i voina 1 (Woman and War), 5 March 1915, p. 3.

- ↑ Ruthchild, Rochelle: Going to the Ballot Box is a Moral Duty for Every Woman. The Great War and Women’s Rights in Russia, in Read, Christopher / Waldron, Peter / Lindenmeyr, Adele (eds.): Russia’s Home Front in War and Revolution, 1914-22. Reintegration – The Struggle for the State, volume 4, Bloomington 2018, pp. 139-176.

- ↑ Preobrazhenskii, A. S.: Materialy k voprosu o dushevnykh zabolevaniiakh voinov i lits, prichastnykh k voennym deistviiam v sovremennoi voine (Materials on the Question of Mental Illnesses of Combatants and Personnel Participating in Military Action in the Present War), Petrograd 1917, pp. 79, 155-156.

- ↑ For extended discussion of the image of these women, see Stoff, Russia’s Sisters of Mercy 2015, chapters 7 and 8.

- ↑ By September 1917, the number of Russian troops wounded in the war was approximately 2.5 million. Another 2.3 million soldiers had contracted contagious diseases such as typhoid fever, typhus, cholera, dysentery, pneumonia, and scurvy. Tsentral’noe Statisticheskoe Upravlenie, Otdel Voennoi Statistiki (The Central Statistical Office, Department of Military Statistics), Rossiia v mirovoi voine, 1914-1918 goda (v tsifrakh) (Russia in World War 1914-1918 (in figures)), Moscow 1925, p. 25.

- ↑ See Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi voenno-istoricheskii arkhiv (Russian State Military-Historical Archive, Moscow, Russia; hereafter RGVIA), f. 2003 (Staff of the Supreme Commander (Stavka), Mogilev), op. 2 (Office of the Duty General), d. 28 (Correspondence with the staffs of the fronts and military districts on the admission of volunteers into the active army), ll. 23, 45, 71-72, 131, for examples of petitions sent to the Russian high command and the tsar by women requesting permission to enlist in the active army.

- ↑ Wildman, Allan: The End of the Imperial Army. The Old Army and the Soldiers’ Revolt (March-April, 1917), Princeton 1980, p. 11.

- ↑ These documents are held in the Russian State Military-Historical Archive in Moscow. Personal accounts include Bocharnikova, Maria: Boi v Zimnem Dvortse (Battle at the Winter Palace), in: Novyi zhurnal (New Journal) 68 (1962), pp. 215-227 as well as Bocharnikova’s papers located in the Bakhmeteff Rare Book and Manuscript Archive, Columbia University; Botchkareva, Maria [sic]: Yashka. My Life as Peasant, Officer and Exile, as set down by Isaac Don Levine, New York 1919; Solonevich, Boris: Zhenshchina s vintovkoi. Istoricheskii roman (Woman with a Rifle: An Historical Novel), Buenos Aires 1955, the “slightly fictionalized memoirs” of Nina Krylova; Yurlova, Marina: Cossack Girl, New York 1936 and Yurlova, Marina: The Only Woman, New York 1937.

- ↑ Stoff, They Fought for the Motherland 2006, pp. 59-69.

- ↑ Report to the minister of war from the Organizing Committee of the Women’s Army (RGVIA, f. 2000, op. 2, d. 1557, l. 48), Zhenshchiny-voiny (Women Warriors), in: Novoe vremia (New Times), 1 June 1917, p. 2. Coded telegram from the military agent in England, OGENKVAR, 1 August 1917 (RGVIA, f. 2000, op. 2, d. 1557, l. 62), Telegramma general-kvartirmeistera Stavki nachal’niky Iugo-Zapadnogo fronta (“Telegram from the General Quartermaster of Stavka to the Commander of the Southwestern Front”), in: Kakurin, N. E. / Iakovleva, Ia. A.: Razlozhenie Armii v 1917 godu (The Disintigration of the Army in 1917), Moscow 1925, p. 72; Zhenskii ‘Batal’on Smerti (The Women’s ‘Battalion of Death), in: Utro Rossii, 2 June 1917, p. 4; and Zhenskie Voennye Organizatsii. Soiuz aktivnoi pomoshchi rodine (Women’s Military Organizations: The Union of Active Aid to the Motherland), in: Utro Rossii (Russian Morning), 6 June 1917, p. 6 for examples of such petitions.

- ↑ List of the staff of the Reserve Company of the 1st Petrograd Women’s Battalion, (RGVIA, f. 2000, op. 2, d. 1557, l. 188); Order No. 10 of the 2nd Moscow Women’s Battalion of Death, 6 July 1917, (RGVIA, f. 3474, op. 2, d. 5, (Documents of the 2nd Moscow Women’s Battalion of Death), l. 7).

- ↑ List of cadets of the Moscow Women’s Battalion of Death (RGVIA, f. 725, op. 54, d. 489 (Documents on the women officers trained in the Aleksandrovskii Military School, l. 19).

- ↑ Zhenskii dobrovol’cheskii komitet (The Women’s Volunteer Committee), in: Armiia i flot svobodnoi Rossii (Army and Navy of Free Russia), 2 July 1917, p. 3, Ustav Vserossiiskogo voennogo zhenskogo soiuza “Pomoshchi Rodine” (Charter of the All-Russian Military Women's Union "Help to the Motherland") (RGVIA, f. 2000, op. 2, d. 1557, l. 194), Dokladnaia zapiska voennomu ministru iz Organizatsionnogo Komiteta Zhenskoi Armii (Memorandum to the Minister of War from the Organizing Committee of the Women's Army)(RGVIA, f. 2000, op. 2, d. 1557, l. 48), and Zhenskie Voennye Organizatsii. Soiuz aktivnoi pomoshchi rodine (Women’s Military Organizations: The Union of Active Aid to the Motherland), in: Utro Rossii (Russian Morning), 6 June 1917, p. 6.

- ↑ See for example, the report from the chief of staff of the I Siberian Army Corps on the actions of the Petrograd Women’s Battalion in the battle of 9 July 1917 at Novospasskii Forest (RGVIA, f. 2277, op. 1, d. 368, l. 1).

- ↑ Documents of the First Siberian Army Corps (RGVIA, f. 2277, op. 1, d. 368); Botchkareva, Yashka 1919, pp. 209-217; Solonevich, Zhenshchina s vintovkoi (Woman with a Rifle) 1955, pp. 120-133.

- ↑ Bocharnikova, Maria: Boi v Zimnem Dvortse (Battle at the Winter Palace), in: Novyi Zhurnal 68 (1982), pp. 215-227; Miscellaneous Correspondence of the War Ministry, RGVIA, f. 2000, op. 2, d. 1557, ll. 211-212.

- ↑ This terminology is derived from Melman, Billie (ed.): Borderlines. Gender and Identities in War and Peace, 1870-1930, New York 1998.

Selected Bibliography

- Alexinsky, Tatiana: With the Russian wounded, London 1916: Fisher Unwin.

- Bocharskaya, Sofiya / Pier, Florida: They knew how to die. Being a narrative of the personal experiences of a Red Cross sister on the Russian front., Peter Davies 1931: London.

- Chelakova, N.: Iz zapisok sestry miloserdii (From the notes of a Sister of Mercy), in: Novoe Russkoe Slovo (New Russian Word), 1969.

- Farmborough, Florence: With the armies of the Tsar. A nurse at the Russian Front in war and revolution, 1914-1918, New York 2000: Cooper Square Press.

- Gatrell, Peter: Russia's First World War. A social and economic history, Harlow 2005: Pearson/Longman.

- Ivanova, Iu. N.: Khrabreishie iz prekrasnykh. Zhenshchiny Rossii v voinakh (The bravest of the beautiful. Russian women in wars), Moscow 2002: Rosspėn.

- Khristinin, Iu. N.: Ne radi nagrad, no radu tokmo rodnogo narodu (Not for the sake of awards, but for the sake of the Russian people), in: Voenno-istoricheskii zhurnal (The Military-Historical Journal) 1, 1994, pp. 92-93.

- Lopatkina, Nataliya L.: Kul’turologicheskie aspekty v razvitii sestrinskogo dela (Cultural aspects in the development of nursing), Kemerovo 2009: Medestra.

- Posternak, A. V.: Ocherki po istorii obshchin sester miloserdiia (Essays on the history of nursing societies), Moscow 2001: Sviato-Dmitrievskoe uchilishche sester miloserdiia.

- Sanborn, Joshua A.: Imperial apocalypse. The Great War and the destruction of the Russian Empire, Oxford 2014: Oxford University Press.

- Sanborn, Joshua A.: Drafting the Russian nation. Military conscription, total war, and mass politics, 1905-1925, DeKalb 2003: Northern Illinois University Press.

- Semina, Khristina D: Tragedii︠a︡ russkoĭ armii pervoi velikoi voiny 1914-1918 gg. Zapiski sestry miloserdiia kavkazskogo fronta (Tragedy of the Russian army in the First Great War 1914-1918. Notes of a Sister of Mercy on the Caucasian Front), New Mexico 1963.

- Senin, A. S.: Zhenskie batal’ony i voennye komandy v 1917 g (Women's battalions and military commands in 1917), in: Voprosy istorii (Problems of History)/10 , 1987, pp. 176-182.

- Solomon, Susan Gross / Hutchinson, John F (eds.): Health and society in revolutionary Russia, Bloomington 1990: Indiana University Press.

- Stoff, Laurie: They fought for the motherland. Russia's women soldiers in World War I and the Revolution, Lawrence, Kan. 2006: University Press of Kansas.

- Stoff, Laurie: Russia's sisters of mercy and the Great War. More than binding men's wounds, Kansas 2015: University Press of Kansas.

- Tolstaia, Alexandra: Doch' (Daughter), Moscow 2000: Vagrius.

- Varnek, T. A / Bocharnikova, M / Mokievskaia-Zubok, Z. S: Dobrovolitsy. sbornik vospominani (Female volunteers. A collection of memoirs), Moskva 2001: Russkii put’.

- Zakharova, Lidiia: Dnevnik sestry miloserdiia (na peredovykh pozitsiiakh, 1914-1915 gg.) (Diary of a Sister of Mercy (on the frontlines, 1914-1915)), Petrograd 1915: Izd-vo biblīoteka "Velikoĭ voĭny".

- Zvereva, N.K.: Avgusteishie sestry miloserdiia (Imperial Sisters of Mercy), Moscow 2006: Veche.