Life↑

The second of four brothers, Walter Flex (1887-1917) grew up in a bourgeois, but impoverished family in Eisenach, Thuringia. After receiving his doctorate in 1911, Flex worked as a private teacher for a number of years for the von Bismarck and the von Leesen families. While there, he struggled for success as a writer of heroic plays and neo-romantic narratives. After the outbreak of the war, Flex first served in Lorraine in the autumn and winter of 1914. In an officer’s training camp near Weißenburg (Biedrusko), he befriended his comrade Ernst Wurche (1894-1915), to whom he dedicated the famous The Wanderer Between Two Worlds. Both were sent to Augustów in the northeast of Poland. Wurche died in battle in Simnas, near Alytus (in today’s Lithuania) in 1915. Flex fought in Vilnius in the autumn of 1915 and against the Lake Naroch Offensive in March 1916. Later that year, he was ordered to Berlin to document the offensive for an official series of monographs, printed in 1919 under the title Die russische Frühjahrsoffensive 1916. Having been drafted to the Baltic Sea in autumn 1917, he participated in Operation Albion and the conquest of the Island Saaremaa (Ösel). He was fatally wounded near Pöide (Saaremaa) and died on 16 October 1917.

War Poetry and The Wanderer Between Two Worlds↑

Flex, ecstatic about the outbreak of war, published a number of martial poems in the Tägliche Rundschau and other papers in the summer and autumn of 1914. Most of his poems proclaimed a collective readiness for battle, conjured loyalty to the Kaiser and to Germany, or versified the "Ideas of 1914". Flex’ most successful poems originated from his first months in battle and discussed the heroic experience in the trenches. Because they drew on the soldiers "real" experiences, but remained decisively nationalist in tone, Flex was soon celebrated as a "new Theodor Körner (1791-1813)". His newspaper poems were republished in over twenty anthologies during the first two war years alone. Flex collected them under the title Das Volk in Eisen. Gesänge eines Kriegsfreiwilligen (Lissa 1914), and later published further poems about life in the trenches entitled Im Felde zwischen Nacht und Tag. Gedichte (Munich 1917, 1920).

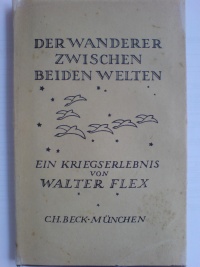

Flex’ considerable success as a war poet has often been dwarfed by the enormous impact of his autobiographical memoir Der Wanderer zwischen beiden Welten, which was reissued thirty-nine times within the first two years of its initial publication in October 1916. By 1933, it had sold over 340,000 copies, making it the second most successful war narrative in the German language, the first being Erich Maria Remarque's (1898-1970) All Quiet on the Western Front (Im Westen nichts Neues). The memoir recounts Flex’ first meeting with his comrade and friend Ernst Wurche, their participation in battles on the Eastern Front, and two days of vacation spent together in nature. The final third narrates Wurche’s death and the narrator’s initial inability to come to terms with it. It is only through recalling Wurche’s idealist philosophy that the narrator finally learns to accept death as the ultimate fulfillment of a soldier’s youthful life. Flex’ ardent admiration of the young, ascetic leader, the sanctification of sacrificing oneself for the nation, and the concept of a loyal trench community struck a chord both with combatants and members of youth movements like the "Wandervögel", of which Wurche had been a member.

Impact and Reception after the War↑

Even though Flex was not appreciated univocally by the National Socialists – the famous Germanist and critic Adolf Bartels (1862-1945) in particular devalued his work – his Wanderer Between Two Worlds was mandatory reading in most schools and was redistributed in cheap editions with thousands of copies. Numerous streets and schools were named after him, and many emphatic "introductions" to and "interpretations" of his works claimed Flex as one of the intellectual forefathers of National Socialism. Partly due to his high regard in the "Third Reich", Flex was rapidly forgotten in the 1960s and 1970s.

Nicolas Detering, Department of German Literature, University of Freiburg

Section Editor: Christoph Nübel

Selected Bibliography

- Koch, Lars: Der Erste Weltkrieg als Medium der Gegenmoderne. Zu den Werken von Walter Flex und Ernst Jünger, Würzburg 2006: Königshausen & Neumann.

- Mergenthaler, Volker: Krieg, Tod, Trauer und Dichtung. Walter Flex’ 'Wanderer zwischen beiden Welten', in: Literaturkritik 2, 2012.

- Neuss, Raimund: Anmerkungen zu Walter Flex. Die 'Ideen von 1914' in der deutschen Literatur. Ein Fallbeispiel, Schernfeld 1992: SH-Verlag.

- Spiekermann, Bernd: Willfährigkeit gegen das Göttliche und Wehrhaftigkeit gegen das Menschliche. Religion und Nation im Werk von Walter Flex, Münster 2000: Schüling.