Introduction↑

British India (comprising today’s India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Burma) joined the First World War on 4 August 1914, as part of the British Empire. At the outbreak of the war, Charles Hardinge, Baron Hardinge of Penshurst (1858-1944), the Viceroy of India, declared that India also was at war, without consulting Indian political leaders. However, in India, the news of the war was received enthusiastically by the native princes, the political bourgeoisie and the educated middle-classes alike, with pledges of imperial loyalty and support. There were two transnational pockets of resistance which caused a considerable deal of imperial panic during the war years: the first was the Ghadr party, settled mostly in North America and Canada, and the second was a dispersed group of cosmopolitan, largely elite, political revolutionaries who came together to form the so-called Berlin Indian Independence Committee. But the activities of each group were isolated and ultimately unsuccessful.[1] On the actual homefront, all seemed relatively quiet during the war years, barring sporadic food riots, occasional skirmishes and moderate nationalist demands – and anxiety and bereavement among particular communities, particularly in the Punjab.

Before further investigating the responses to the war within the home front, it is worthwhile to briefly note India’s war contributions. From August 1914 until December 1919, India recruited for purposes of war 877,068 combatants and 563,369 non-combatants, making a total of 1,440,437;[2] in addition, there were an estimated 239,561 men in the British Indian army in 1914, including both combatants and non-combatants, and around 20,000 in the Imperial Service Corps.[3] India also made a substantial contribution in terms of cash, animals, transport and material. Alongside manpower, the “jewel in the British crown” contributed its vast resources even as it bled internally. These ranged from minerals (iron, mica and manganese), military hardware and transport equipment to grains, cotton, jute, wool and hide, to 185,000 animals, including horses, camels and mules. It also made a direct financial commitment. The statute governing India’s relationship to Great Britain was amended so that India could “share in the heavy financial burden”. There was a free lump sum gift of 100 million pounds to “His Majesty’s Government” as a “special contribution” by India towards expenses of war which was partly raised through war bonds; and in the five years ending with 1918-1919, its total net military expenditure, excluding the special contribution and costs of special services, amounted to 121.5 million pounds.[4]

State of Research and Source Material↑

Over the last century or so, there has been a large degree of amnesia across much of India – except in places such as the Punjab which contributed more than half the number of combatants – about the country’s role in the conflict. The Indian soldiers were fighting for the British Empire at the time of the first nationalist stirrings and thus fell on the wrong side of history in post-independence India. There has, however, been sporadic scholarly interest in India’s role in the war. In recent years, there has been a fresh swell of interest in India and the war, and the performances and experiences of the India troops, particularly in Europe, are being reassessed.[5]

Less attention has been paid to the social and cultural responses to the war within India. However, some of the contemporary accounts are illuminating, even if they provide an imperial perspective. These include the compendious All About the War: India Review War Book (1915) by G. A. Natesan (1873-1948), the anonymous India and the War (1915), and Punjab and the War (1922) by M. S. Leigh, with plenty of extracts about the various debates regarding India’s war participation. However, these works inevitably provide us with the responses of the elite and the educated. There has been some interest in recent years in the processes of recruitment, as in the excellent work by scholars such as Tan Tai Yong and David Omissi. But we are still a long way from gauging the responses of the various village communities in the Punjab, Central India or the North West Frontier province from where most of the soldiers were recruited, in accordance with the theory of the “martial races”.

Eurocentrism or elitism is, however, only part of the problem. Most of the soldiers came from non- or semi-literate backgrounds; the literacy rates in the Punjab at the time was only 5 percent. We do not have anything like the diaries or journals or poems by women and civilians which help to chart the responses on the European home front. But amnesia does not mean absence. There is often a powerful but subterranean vein of memory; one needs to go beyond conventional sources such as archival documents, diaries and letters, and delve into alternative sources such as war artifacts, oral narratives and songs which help us to recover this silent front. In the last couple of years, fresh material has been unearthed, including poems, qissas (stories) and folksongs which help us to capture some of these lost voices; moreover, archival records of recruitment at the district levels give us better insights into the social processes of mobilization in many of these places.

Responses from the Native Princes↑

In August 1914, when the King-Emperor sent a message to the “Princes and People of My Indian Empire”, the responses from the feudal princes were extremely enthusiastic.[6] They still ruled around one-third of India with varying alliances and partnerships with the British Raj. They made vast offers of money, troops, labourers, hospital ships, ambulances, motorcars, flotillas, horses, food and clothes. The Imperial Service troops of all the twenty-seven states in India were placed at the disposal of the Viceroy. Sir Pertab Singh (1845-1922), Regent of Jodhpur and a favourite of Victoria, Queen of England (1819-1901), threatened to go on a hunger-strike if he were not allowed to go and fight. Kapurthala was one of the first states to pledge its resources while the Maharajah of Bikanir, offering 25,000 men, noted: “I and my troops are ready to go at once to any place either in Europe or in India or wherever”.[7] Indeed, the native princes vied with each other to serve at the front, and on 9 September 1914, when the names of those selected by the Viceroy for service in Europe – the chiefs of Bikanir, Patiala, Coochbehar, Jodhpur, Rutlam and Kishengarh, among others – were announced, it caused a sensation in the House of Commons.

Vast sums of money flowed in from native princes according to their wealth, from a contribution of Rs 50 lakhs from the Maharajah of Mysore to Rs 5 lakhs from the Maharajah Gaekwar of Baroda (1863-1939) for the purchase of aeroplanes for the Royal Flying Corps.[8] There were also interest-free loans such as the offer of Rs 50 lakhs from Gwalior. In addition to cash contributions, there were specific gift items, from clothes, food grains and objects of daily use such as lotas (brass drinking-vessels) to religious items: the Begum of Bhopal sent 500 copies of the Koran and 1,487 copies of religious tracts for the Muslim soldiers. The Maharajah of Patiala similarly sent Romals (covers spread on the Granth) and Chanani to the Sikh prisoners in Germany.[9] He also offered a flotilla of motorcars for use in Mesopotamia.[10] The munificence of the princes was duplicated by smaller landowners and chieftains: the Thakur of Bagli thus contributed Rs 4000 for the comforts of the Indian troops in East Africa, Mesopotamia and Egypt: “Socks, shirts, mufflers, waistcoats, cardigan jackets...tobacco, cigarettes, chocolates”.[11]

Different motives were fused and confused in these extravagant offers. Many of these princes had long family traditions of imperial alliances, as in the following speech by the Nizam of Hyderabad:

Some of the princes, such as Sir Pertab Singh and Maharaja Ganga Singh of Bikaner (1880-1943), had served in the imperial wars in China in 1900; some had received honours during the Coronation Durbar in 1911, such as the title of “Major-General” conferred on Maharajadhiraj Madho Singh of Jaipur. Above all, dependent for their continued existence on the British Raj, these native princes seized upon the war as an opportunity to demonstrate their loyalty. Consider the following speech delivered by the Prince of Alwar in January 1917 at a Princes’ banquet held in the honour of the Maharajah of Bikaner: “We desire to prove by deeds that we appreciate the recognition of our rights and privileges which has been the touchstone of the policy of British rules in India. ... When such constitutional changes take place, it is not possible to think that the destinies of our one-third India are likely to be ignored.”[13]

Turkey’s entrance into the war on 28 October 1914 caused fresh panic: will the Indian Muslims continue to serve under the British and fight their religious brethren? On 14 November 1914, in Constantinople, the Sheikh-ul-Islam declared a holy religious war against the Western nations including Britain, France and Russia. As Hew Strachan observes, “This was a call to revolution which had, it seemed, the potential to set all Asia and much of Africa ablaze”.[14] The Muslim rulers were called upon to reassure their subjects and keep their morale high. Thus, at the Delhi War Conference in April 1918, the Begum of Bhopal (1858-1930) noted:

Echoing the Begum’s exhortations, we have similar appeals from the Nizam of Hyderbad (1886-1967), the Nawab of Palanpur as well as the Aga Khan (1877-1957), telling their subjects that “at this critical juncture it is the bounden duty of the Mohammedans of India to adhere firmly to their old and tried loyalty to the British Government”.[16]

The political bourgeoisie and educated classes↑

The First World War brings out within the Indian political bourgeoisie a strange conjunction of imperialist zeal and nationalist aspirations that defy the neat retrospective political narratives of either imperialism or nationalism. Instead, these responses testify to a complex “structure of feeling”, showing that in colonial India during the war, the two were not always as water-tight or antithetical as we believe them to have been. If the news of the outbreak of the war was greeted in India with a widespread rhetoric of loyalty and support for the empire, the years 1914-1918 also saw a burgeoning sense of nationalism. During the war years, there was a more concerted movement for self-rule in India than ever before, as leaders such as Annie Besant (1847-1933) and Gangadhar Tilak (1856-1920) launched the Home Rule League in 1916 and used India’s war contributions to demand self-government within the empire.[17]

On 12 August 1914 Dadabhai Naoroji (1825-1917), one of the founding figures of the Indian National Congress, describing himself as “more of a critic than a simple praiser of the British Rule in India” noted: “the vast mass of humanity of India will have but one desire in his heart viz., to support … the British people in their glorious struggle for justice, liberty, honour”.[18] The Indian National Congress of 1914, dominated by political moderates such as Bhupendranath Basu (1859-1924) and Surendranath Banerjee (1848-1925), who believed in the gradual attainment of self-government by evolution rather than by revolution, pledged their whole-hearted support to the Allies.[19] Different political parties and communities such as the All India Muslim League, Madras Provincial Congress, Hindus of Punjab and the Parsee community of Bombay concurred. Fund-raising was organised and meetings were held in cities such as Calcutta, Bombay, Lahore and Allahabad. Pamphlets were produced pledging support, one typical title (1915) being: “Why India is Heart and Soul with Britain.”[20] Addressing a big gathering in Madras, Dr. Subramania Iyer (1842-1924) claimed that to be allowed to serve as volunteers is an “honor superior to that of a seat in the Executive Council and even in the Council of the Secretary of State”.[21]

The strategic calculation between war service and demand for greater political autonomy is most evident in the wartime writings of the Irish theosophist Annie Besant, who joined the National Congress in 1914 and would be its guiding spirit for the next three years.[22] Besant passionately championed India’s demand for self-government, or “Home Rule”, not as a completely autonomous country but rather as a “Free nation in the Federated Empire”.[23] To Besant, the war was the ideal opportunity for India to demonstrate its loyalty and support to the empire, and thus earn the right of self-government. In her article, “India’s Loyalty and England’s Duty”, she states:

Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) however demurred. In his autobiography, he notes: “I thought that England’s need should not be turned into our opportunity, and that it was more becoming and far-sighted not to press our demands while the war lasted.”[25]

Gandhi, who was raising an Ambulance Corps in London in 1914, threw himself whole-heartedly into the recruitment drive on his return to India in 1915. He argued that “we should send our men to France and Mesopotamia. We are not entitled to demand Swaraj [self-rule] till we come forward to enlist in the army”. For this most celebrated prophet of non-violence, the war strangely was not just caught up in the future bid for political freedom, but also in complex discourses of martial masculinity. He opined: “Here we have an invaluable opportunity for getting back the capacity to fight which we have lost and we should not miss the supreme opportunity which India has of supplying half a million men.”[26] Later however, Gandhi would completely reverse his stance, and ask Indians not to join the British army. But in 1914, even Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) – who had won the Nobel Prize in 1913 and would later decry the war in his powerful lectures on Nationalism in Japan and the US – was tempted to publish verses supporting the war in The Times:

Let hard blows of trouble strike fire into my life.

Let my heart beat in pain – beating the drum of victory.[27]The First World War caught the Indian educated middle-class psyche at a fragile point between a residual loyalty to the empire and a restless nationalist consciousness – very different from the country’s position during the Second World War. Fund-raising was organised, meetings were held in cities such as Calcutta, Bombay, and Lahore, special prayers were offered in mosques; it was said that even Goddess Kali has been enlisted for the Allied cause! A literary war journal, The Indian Ink, was produced and a recruitment play, Bangali Polton, was written and staged in Calcutta. For many Indians, imperial war service curiously became a way of salvaging national and regional prestige, something revealed in the wartime speeches and writings of another much younger woman nationalist: Sarojini Naidu (1879-1949). Actively involved in the war efforts through the Lyceaum Club in London, she then returned to India and made the following appeal at the Madras Provincial conference in 1918:

The smarting phrase “nation of shopkeepers” leaps out of the page and reveals why this nationalist, whose aim was to “hold together the divided edges of Mother India’s cloak of patriotism”, would support India’s war service. Being constantly made to feel small before the “superior” civilisation of the West and still smarting under the perceived “blemish” of the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, the majority of the Indians saw the First World War as an opportunity to set aright the racial slur and prove at once their courage and loyalty.

Indeed, India’s massive war contribution no doubt contributed to Edwin Montagu’s (1879-1924) declaration in 1917 that “the progressive realization of responsible self-government” would be the aim of British rule in India. Yet, as the war ended, promises were broken. The Rowlatt Act of 1919 carried wartime ordinances into peacetime legislation – giving powers to the British to imprison Indians without trial – and infuriated people. Gandhi condemned the “black” act passed by a “satanic” government.[29] A watershed moment was the Jallianwallah Bagh massacre on 13 April 1919 at Amritsar in Punjab. The post-war years saw Gandhi’s rise to power in nationalistic politics. The relations between the First World War and the Indian independence movement are complex and vital, and it is not possible to draw a direct, linear trajectory between the two. But the war did bolster the confidence and political awareness of many of the troops and gave a fillip to the nationalistic movement. As a Punjabi veteran of the First World War noted in 1972, “when we saw various peoples and got their views, we started protesting against the inequalities and disparities which the British had created between the white and the black”.[30]

Subaltern Responses↑

But what do we know about the responses of the rural communities from where the men actually enlisted and went to fight? Almost half of them, including 349,688 combatants and 97,288 non-combatants, came from the Punjab; in districts such as Jhelum and Rwalpindi, 40 percent of all males of military age enlisted. By 1917, the recruitment base had been broadened.[31] By the end of the war, Punjab provided 370,609 combatant recruits, including 190,078 Muslims, 97,016 Sikhs and 83,515 Hindus.[32] The non-combatant labourers, often termed “followers” – mule-drivers, langri (cook), bhisti (water-carrier), mochis (saddler), dhobis (washermen), and barbers – came from a different recruitment base.[33]

While we have the recruitment statistics, often at a district level, we hitherto have had almost no testimonies of how the men and the women from the remote rural villages in the Punjab or North West Frontier Province actually responded: was it the roar of battle conveyed through the drums of the recruiters and the sepoys’ letters, or just a whisper in the fields amidst the scorching sun? To reconstruct their responses or emotions involves reading colonial posters and documents against and along the grain. However, in the last couple of years, some fresh material, including articles published in local newspapers and journals such as the Jat Gazette, wartime verses and folksongs, as well as some war medals and stone plaques found in local schools (constructed with the money sent home by the soldiers) have been unearthed. These help us to gauge some of the emotional responses.

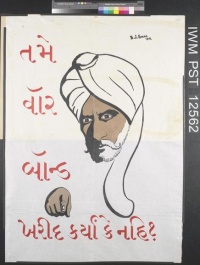

Recruiting was often done on an informal basis. NCOs, sepoys, local recruiters and zaildars (officers in charge of a Zail or administrative units extending over several villages) would often go to the villages and were in turn promised medals, promotions and land-grants. A contemporary poster – showing an empty military uniform, a rifle and a handful of coins – summed up the threefold attraction of uniform, money and masculinity that often led men to enlist. Financial motive, family and community traditions, social pressures, a desire for adventure and occasional coercion by the colonial state seem to be combined.

Given that the majority of the potential recruits were non-literate, the recruitment campaign used oral modes of transmission. Some of these songs and verses help us to reconstruct – though to a tantalisingly incomplete degree – the emotional climate of the time. For example, in the Karnal district of the Punjab, singers were commissioned to compose recruitment songs which were performed in the evenings, often on popular village occasions; after such performances, young men were asked to line up and enlist.[34] In Punjab a series of recruitment meetings were held in villages such as Rohtak, Jhajjar, Sanghi, Becchedi and Rohana. A contemporary report, published in the Jat Gazette (in Urdu) helps us to reconstruct some of the atmosphere:

Molad Singh, hermit, (Village- Rewada) played and sang a folk song that narrated a tale of war.

Bhagwan Das (teacher) encouraged the recruits to enlist for the war through a hymn.

Officers too encouraged people to enlist in the army

People contributed the following for the wounded and other soldiers:

- Chaudhari Sriram, Zaildar, ThaskaTobacco – 38 packets

- Chaudhari Deshram, Rithal“ – 4 packets

- Captain Gugan Singh Bahadur“ – 1 seers

- Chaudhari Giriraj Singh, Aanwali“ – 4 seers

- Chaudhari Shiv Singh, Zaildar, Balyaali“ – 4 packets

- Chaudhari Mohanlal, Safedposh, Bhawal Kala“– 4 packets

- Ramji Lal, Nambardar[Head], Rithal “ – 1 seers

- Saalik, Head, Rewara“ – 5 seers

- Chaudhari Rahmatullah, Nambardar[Head], Kasani “ – 16 packets

- Kalwa, Head, Rewara“ – 5 seers

- Kude Singh , Jasrana“ – ½ seer of pickle

Such reports are often the closest we come to understanding such processes. In addition to traditional war songs, fresh recruitment songs were commissioned, composed and sung, like the following one:

Here you get torn rags, there you’ll get suits, get enlisted…

Here you get dry bread, there you’ll get biscuits, get enlisted…

Here you’ll have to struggle, there you’ll get salutes, get enlisted…[36]What is striking is the absence of any appeal to imperial loyalty or the so-called, oft-quoted izzat (honour or prestige):[37] like the war poster discussed earlier, what we have is a direct appeal to food, money and clothes, revealing the priorities of the potential recruit.

At the same time, inevitably, there was an alternative tradition of verses and songs, partly formed in reaction against men being called away to war, never to return. In some of the poems there was not just lament and mourning but also a powerful critique of the war:

Why should the nephew not be shocked, seeing Uncle play holi with Aunty!

Springs of blood are flowing in Europe, in what new colours have arrived the old Holi.

OR

Germany has been going on with its ‘chaaein chaeein’ for four years, crows are teasing lions with kaeein kaeein

During the war years, India’s defence expenditure was increased by some 300 percent, and currency circulation rose from Rs 660 million in 1914 to Rs 1530 in 1919.[39] There was wide-spread inflation and prices of essential commodities – cloth, kerosene oil and food grain – shot up.

In 1917, a quota system was introduced by which each province had to provide a minimum number of combatants, and in some areas, a system of “compulsory voluntary” recruitment was introduced. Occasionally coercion was used, as in Multan. And this system was not just restricted to combatants. In 1917, the Indian government agreed to provide 50,000 labourers for France, organised into units of 500, which made up the 21st to 85th Indian Labour Companies. The recruitment for the Indian Labour Corps was done so aggressively that it sparked an uprising in the Kuki-Chin tracts in the Assam-Burma border and in Mayurbhanj, Orissa.[40] Aggressive recruitment also led to some resistance – from wives, mothers and daughters. Women would sometimes trail their freshly recruited men for miles, trying to win them back; in the play Bengal Platoon, the mother of a new recruit curses the “red-faced monkeys” – i.e. the British recruiter – for stealing her son. Interestingly, what survives about the war in the cultural-aural memory of the Punjab comes from women who often wove their protest and despair into songs:

All have gone to laam. [l’arme]

Hearing the news of the war

Leaves of trees got burnt.

Without you I feel lonely here.

Come and take me away to Basra.

I will spin the wheel the whole night.

…

War destroys towns and ports, it destroys huts

I shed tears, come and speak to me

All birds, all smiles have vanished

And the boats sunk

Graves devour our flesh and blood.[41]According to the British Punjabi poet Amarjit Chandan, who has excavated many of these songs, “They [the women] hate war and the warmongers, whether the British or the Germans. ... There is nowhere any hint of martyrdom in these songs. They knew their men were mercenaries and not fighters in the Sikh or Rajput or jihadi tradition.”[42] In 2007, I interviewed in Kolkata the Punjabi novelist Mohan Kahlon who mentioned how his two uncles – peasant-warriors from Punjab – perished in Mesopotamia, and his grandmother became deranged with grief; in the village, their house came to be branded as “garod” (the asylum).[43] War trauma here spilled into the furthest reaches of the empire.

Conclusion↑

Like the war experience of the more than 1 million troops who served abroad, there was no monolithic or uniform response to the war within India: it has to be nuanced to other factors such as class, caste, region, district and gender, among others. Responses also sharply differed over the course of the four years. While responses to the war on the non-white colonial homefront remain some of the most understudied and least understood areas of First World War studies, there is a fresh swell of interest in recent years to mobilize a greater number of sources – from objects, artefacts, medals and letters, to district reports, wartime plaques and songs – to understand more fully such responses. Efforts are being made by the United Services Institution, a military research think-tank at New Delhi, to gather such reports, which are held in various places, including Great Britain and Pakistan.[44] Hopefully, one of the more enduring outcomes of the focus on the war during its four centennial years would be a greater understanding of this area.

Santanu Das, King's College London[45]

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Notes

- ↑ See: Singh, Gajendra: Revolutionary Networks (India), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-12-19. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1546333/ie1418.10523.

- ↑ The above figures are from: Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914-1920, London 1922, p. 777. It notes that between August 1914 and December 1919, India had sent overseas 1,096,013 (Indian) men, including 621,224 soldiers, both officers and other ranks, and 474,789 non-combatants.

- ↑ Ibid. Also see: Jack, George Morton: The Indian Army on the Western Front. India’s Expeditionary Force to France and Belgium in the First World War, Cambridge 2014, pp. 1-3.

- ↑ India’s Contribution to the Great War, Calcutta 1923, pp. 156, 161.

- ↑ See: Ellinwood, Dewitt/Pradhan, S.D. (eds.): India and World War I, Delhi 1978. Most histories of modern India however mention the war, including: Sarkar, Sumit: Modern India, 1885-1947, Madras 1983; and Bose, Sugata / Jalal, Ayesha: Modern South Asia, Delhi 2004. For recent histories, see Pati, Budeshwar: India and the First World War, Delhi 1996; Omissi, David: The Sepoy and the Raj, Basingstoke 1994; and Omissi, David (ed.): Indian Voices of the Great War 1914-1918, Basingstoke 1999; Corrigan, Gordon: Sepoys in the Trenches. The Indian Corps on the Western Front 1914-1918, Staplehurst 1999; Tai-Yong, Tan: The Garrison State. Military, Government and Society in Colonial Punjab, London 2000; Roy, Franziska/Liebau, Heike/Ahuja, Ravi (eds.): ‘When the War Began, We Heard of Several Kings’. South Asian Prisoners in World War I Germany, Delhi 2011; Singh, Gajendra: The Testimonies of the Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars. Between Self and Sepoy, London 2014; and Jack, The Indian Army on the Western Front 2014.

- ↑ Quoted in: India and the War, London 1915, pp. 40-41.

- ↑ S.R. (ed.): Speeches of Indian Princes on the World War, India 1919.

- ↑ National Archives of India, Delhi (henceforth NAI) Foreign and Political, Internal B, April 1915 Nos. 319; West Bengal State Archives, Calcutta, Political (Confidential), 1915 Proceedings 505.

- ↑ Punjab Government Civil Secretariat, Political Part B, Feb 1917, 6427/74, pp. 139-143.

- ↑ Punjab Government Civil Secretariat, Part B, Oct 1917, 6336, pp. 138-139.

- ↑ NAI, Foreign and Political, Internal B April 1915, Nos. 972-977.

- ↑ Bhargava, M.B.L.: India’s Services in the War, Allahabad 1919, p. 51.

- ↑ S.R., Speeches of the Indian Princes on the World War, p. 2.

- ↑ Strachan, Hew: The First World War, London 2003, pp. 99-100.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 278-80.

- ↑ Indian Mussalmans and the War, in: Natesan, G.A. (ed.): All About the War. The India Review War Book, Madras n.d., 1915?, p. 269. For a detailed account, see: Prasad, Yuvaraj Deva: The Indian Muslims and World War I, New Delhi 1985.

- ↑ Owen, H. F.: Towards nation-wide agitation and organization. The Home Rule Leagues, 1915-1918, in: Low, D. A. (ed.): Soundings in Modern South Asian History, Berkeley, CA 1968, pp. 159-195.

- ↑ Naorji, Dadabhai: (12 August 1914) Message, in: Natesan, G.A (ed.): The Indian Review War Book, Madras n.d., 1915?, Preface (opposite contents page).

- ↑ Basu, Bhupendranath: The Indian Political Outlook, quoted in: Argov, Daniel: Moderates and Extremists in the Indian Nationalist Movement 1883-1920, Bombay 1967, p. 142.

- ↑ Basu, Bhupendranath: Why India is Heart and Soul with Britain in this War, London 1914.

- ↑ Quoted in: India and the War, Lahore n.d., pp. 34-35.

- ↑ See: Kumar, Raj: Annie Besant’s Rise to Power in Indian Politics 1914-1917, New Delhi 1981. Also see an early but excellent essay by Roger Own: Owen, Towards nation-wide agitation and organization. I have drawn on his work for some facts about the Home Rule movement, and have tried to connect them with the discourses on the war.

- ↑ Besant, Annie: To my Brothers and Sisters in India, National Archives of India, Home Department, Political Deposit, March 1918 No.14; also in New India 1 March 1917. See: Chakravorty, Upendra: Indian Nationalism and the First World War (1914-1918), Calcutta 1997, p. 60.

- ↑ Natesan (ed.), All About the War, p. 267.

- ↑ Gandhi, M. K.: An Autobiography or, The Story of My Experiments with Truth, (trans.: Desai, Mahadev) Harmondsworth 1982, p. 317.

- ↑ Gandhi, Mahatma: Collected Works, London 2006, Volume 15, pp. 1-3.

- ↑ War Poems from The Times, issued with The Times, 9 August 1915, p. 10. Also see Das, Santanu: India, Empire and First World War Writing, in: Boehmer, Elleke / Chaudhuri, Rosinka (eds.): The Indian Postcolonial. A Critical Reader, London 2010, pp. 297-305.

- ↑ Quoted in: Bhargava, India’s Services in the War 1919, pp. 208-209.

- ↑ See Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy, Oxford 2004, pp. 102-119, for further details. The reference to Gandhi can be found on page 110.

- ↑ Interview with Lance-Naik Khela Singh conducted by Ellinwood and Pradhan, quoted in: Pradhan, The Sikh Soldier, p. 224.

- ↑ The Punjab District War Histories, IOR, PO 55540, 5545 and 5547. Also see: Mazumder, Rajit: The Indian Army and the Making of Punjab, New Delhi 2003; and Tai-Yong, The Garrison State 2005.

- ↑ Leigh, M. S.: The Punjab and the War, Lahore 1922, p. 44.

- ↑ Singha, Radhika: Front Lines and Status Lines. Sepoy and ‘Menial’ in the Great War 1916-1920, in: Liebau, Heike, et. al. (eds.): The World in World Wars. Experiences, Perceptions and Perspectives from the South, Leiden 2010, pp. 55-106.

- ↑ See Jat Gazette, 15 January 1918.

- ↑ Jat Gazette, 25 December 1917.

- ↑ ‘Recruitment song’ as extracted in First World War 1914-1918: Jat Gazette, translated by Arshdeep Singh.

- ↑ Izzat, an Urdu word roughly translated as honour or prestige, is a remarkably complex and polysemous term: see: Das, Santanu: Indians at home. Mesopotamia and France, 1914-18, in: Das, Santanu (ed.): Race, Empire and First World War Writing, New York 2011, pp. 82-83.

- ↑ Extracted from Bahar-e-Jarman (Bombay?, 2 December 1915) Original in Urdu. Also see: Das, Santanu: Indian Sepoy Experience in Europe. Archive, Language and Feeling, in: Twentieth Century British History, September 2014, pp. 1-27.

- ↑ Bose / Jalal, Modern South Asia 2004, p. 103. Also see: Pati, India and the First World War 1996.

- ↑ Radhika Singha, Encyclopaedia.

- ↑ This song is quoted from Amarjit Chandan, ‘How they Sufferered: World War One and its Impact on Punjabis’, http://apnaorg.com/articles/amarjit/wwi (accessed on 7 August, 2014).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Interview conducted with Mohan Kahlon in Kolkata, 20 December 2007.

- ↑ See Chinna, Rana: ‘India and the Great War’, http://blogs.icrc.org/new-delhi/2014/04/11/usi-mea-world-war-i-centenary-tribute-project-to-shed-new-light-on-indias-role.

- ↑ Archival Records used for this article: National Archives of India, Delhi; West Bengal State Archives, Calcutta; Punjab Secretariat Archive, Chandigarh; Jat Gazette, 1917-1918; India Office Records and Library, British Library.

Selected Bibliography

- Anand, Mulk Raj: Across the black waters, Jonathan Cape 1940: London.

- Bhargava, Mukat Bihari Lal: India's services in the war, Allahabad 1919: Standard Press.

- Bose, Arun: Indian revolutionaries abroad, 1905-1922. In the background of international developments, Patna 1971: Bharati Bhawan.

- Bose, Sugata / Jalal, Ayesha: Modern South Asia. History, culture, political economy, New Delhi; New York 2004: Oxford University Press.

- Corrigan, Gordon: Sepoys in the trenches. The Indian Corps on the Western Front, 1914-1915, Staplehurst 1999: Spellmount.

- Das, Santanu: India, empire and writing the First World War, in: Boehmer, Elleke / Chaudhuri, Rosinka (eds.): The Indian postcolonial. A critical reader, London 2010: Routledge, pp. 297-315.

- Das, Santanu: Ardour and anxiety. Politics and literature in the Indian homefront, in: Liebau, Heike / Bromber, Katrin; Lange, Katharina et al. (eds.): The world in world wars. Experiences, perceptions and perspectives from Africa and Asia, Leiden 2010: Brill, pp. 341-368.

- Ellinwood, DeWitt C. / Pradhan, Satyendra Dev. (eds.): India and World War 1, New Delhi 1978: Manohar.

- Leigh, Maxwell Studdy: The Punjab and the war, Lahore 1922: Printed by the Superintendent, Government Printing.

- Liebau, Heike / Bromber, Katrin / Lange, Katharina et al. (eds.): The world in world wars. Experiences, perceptions and perspectives from Africa and Asia, Leiden 2010: Brill.

- Mazumder, Rajit K.: The Indian Army and the making of Punjab, Delhi 2003: Permanent Black.

- Morton Jack, George: The Indian Army on the Western front. India's Expeditionary Force to France and Belgium in the First World War, Cambridge 2014: Cambridge University Press.

- Natesan, G. A.: All about the war. The Indian review war book, Madras 1915: G.A. Natesan & Co.

- Omissi, David: The Sepoy and the Raj. The Indian Army, 1860-1940, Basingstoke 1994: Macmillan.

- Omissi, David (ed.): Indian voices of the Great War. Soldiers' letters, 1914-18, Basingstoke 1999: Macmillan Press.

- Owen, Hugh F.: Towards nation-wide agitation and organisation. The Home Rule Leagues, 1915-18, in: Low, Donald Anthony (ed.): Soundings in modern South Asian history, Canberra 1968: University of California Press, pp. 159-195.

- Pati, Budheswar: India and the First World War, New Delhi 1996: Atlantic Publishers and Distributors.

- Ramnath, Maia: Haj to utopia. How the Ghadar movement charted global radicalism and attempted to overthrow the British Empire, Berkeley 2011: University of California Press.

- Roy, Franziska / Liebau, Heike / Ahuja, Ravi (eds.): 'When the war began we heard of several kings'. South Asian prisoners in World War I Germany, New Delhi 2011: Social Science Press.

- Sarkar, Sumit: Modern India, 1885-1947, Madras 1983: Macmillan.

- Singh, Gajendra: The testimonies of Indian soldiers and the two world wars. Between self and Sepoy, London 2014: Bloomsbury.

- S.R. (ed.): Speeches of Indian princes on the World War, Allahabad 1919.

- Strachan, Hew: The First World War, New York 2003: Viking.

- Sydenham of Combe, George Sydenham Clarke (ed.): India and the war, London; New York 1915: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Tan, Tai Yong: The garrison state. The military, government and society in colonial Punjab 1849-1947, Delhi 2005: Sage.