Politics of the Right↑

Japan’s experience in the First World War is one of the greatest overlooked tales of the early 20th century.[1] Tangential to the principal narrative of European battles, contemporary sources, however, reveal the remarkable degree to which members of the Entente and Central Powers scrambled for Japanese aid.[2] Historians of modern Japan typically forego in-depth analyses of the 1914-1918 years in favor of accounts of the Russo-Japanese (1904-1905) and “Fifteen Years’” Wars (from the Manchurian Incident in 1931 to military defeat in 1945). Despite over 7,000 miles of separation from the Western Front, however, Imperial Japan underwent a political transformation during the First World War almost as dramatic as that in the vanquished capitals of Europe. As was the case with most belligerents, the outbreak of war in August 1914 initially drove politics to the right in Tokyo. By 1918, however, the tangible consequences of dramatic wartime economic growth transformed the national political landscape. By the time of the Paris Peace Conference, Japan was well on its way to a new 20th -century polity.

| |

|

|

|

| Ōkuma Shigenobu | None | April 1914 – October 1916 | |

| Katō Takaaki | Dōshikai | April 1914 – August 1915 | |

| Ōkuma Shigenobu | None | August 1915 – October 1915 | |

| Ishii Kikujirō | None | October 1915 – October 1916 | |

| Terauchi Masatake | None | October 1916 – September 1918 | |

| Terauchi Masatake | None | October 1916 – November 1916 | |

| Motono Ichirō | None | November 1916 – April 1918 | |

| Gotō Shinpei | None | April 1918 – September 1918 | |

| Hara Takashi | Seiyūkai | September 1918 – November 1921 | |

| Uchida Yasuya | None | September 1918 – November 1921 |

Table 1: Japan’s Wartime Cabinet Heads and Foreign Ministers

Growing Pangs of a Modern Polity↑

Following the overthrow of the feudal dynasty in 1868, Imperial Japan had, in the latter 19th century, introduced all the institutions of a modern polity: compulsory education (1872), prefectural assemblies (1878), peerage system (1884), cabinet system (1885), Imperial University system (1886), and civil service exam (1887). Japan’s first national political party, the Aikokusha (Patriotic Society) was formed in 1875 to advocate constitutional government and local and national assemblies. By 1882, the successor to the Aikokusha, the Jiyūtō (Liberal Party), and the newly formed Rikken Kaishintō (Constitutional Progressive Party) led the “Freedom and People’s Rights Movement,” which, by 1890, succeeded in pressuring the government for a national constitution and parliament. At the time of Sarajevo, however, direct involvement in politics remained the prerogative of a small body of landed and titled men. Only 1.5 million men met the annual tax requirement of ten yen to vote (2.6 percent of the population) in 1914: and policy-making rested firmly with a handful of former samurai primarily from the Satsuma and Chōshū domains, who had spearheaded the latter 19th century reforms and continued to enjoy close proximity to the emperor.

As in modern Europe and the United States, politics in Imperial Japan developed in unexpected ways. Under the Meiji Constitution (1890), all laws required the assent of both the emperor and each house of parliament (known as the Imperial Diet). A parliamentary veto over the budget, moreover, could be overridden by continuing the budget from the previous year. Despite their attempt to institutionalize parliamentary weakness, however, the founders of modern Japan were forced to dissolve the Imperial Diet three times and prorogue it twice in its first four years of operation. After having initially vowed not to permit any role for political parties, moreover, the father of the Meiji Constitution, Count Itō Hirobumi (1841-1909), founded a political party of his own in 1900. The Constitutional Association of Political Friends (Rikken Seiyūkai) enjoyed a majority in the Lower House until the Twelfth General Election of March 1915.[3]

War as “Divine Aid”↑

As in the principal capitals of Europe, the outbreak of war brought initial delight in Tokyo. Just as British prime minister David Lloyd George (1863-1945) hailed the chance to rediscover “the great peaks we had forgotten, of Honour, Duty, Patriotism, and, clad in glittering white, the great pinnacle of Sacrifice pointing like a rugged finger to Heaven,”[4] Japanese elder statesman Inoue Kaoru (1835-1915) praised the war as the “divine aid of the new Taishō era for the development of the destiny of Japan.”[5] Like his European counterparts, Inoue and his countrymen welcomed the end of uncertainty that had accompanied the rapid industrialization of the late 19th century. In the case of Japan, the Russo-Japanese War had also been a major turning point. Military victory in 1905 had confirmed the success of the grand nation-building enterprise embarked upon by modern Japan’s founders in the latter 19th century. Peace, the Chinese Revolution (1911) and the death of the preeminent symbol of the nation-building effort, the Meiji Emperor (reigning 1868-1912) had, however, raised serious questions about the future trajectory of the empire.

As an elder statesman (genrō), Inoue’s greatest expectation in 1914 rested with the potential political boon of a general war in Europe. The Russo-Japanese War had marked the height of political power for Japan’s genrō. With one of their number serving as prime minister - Katsura Tarō (1848-1913) - chief of the Army General Staff - Yamagata Aritomo (1838-1922) - and commander of Japanese forces in the field - Ōyama Iwao (1842-1916) - the elder statesmen had controlled the most critical components of wartime decision-making, without interference from the cabinet or political parties. Following the Portsmouth Peace, however, the parliament had balked at funding for an expanded military force, and an Army bid to compel parliamentary support brought the dissolution of one cabinet and, in 1913, the first toppling of an oligarchic cabinet by a coalition of political parties.

This “Taishō Political Crisis” was very much on the minds of Japan’s elder statesmen as they called upon one of their own, Ōkuma Shigenobu (1838-1922), to form a non-party cabinet in April 1914 (cabinet from April 1914 to October 1916). It was also a pressing concern when Inoue hailed the Great War in August 1914 as “divine aid.” In fact, as had been the case in Imperial Japan’s first two modern wars against China and Russia, respectively, the First World War united public opinion around expectations for an extraordinary opportunity. As journalist Nakano Seigō (1886-1943) declared in the popular bi-weekly, Nihon oyobi Nihonjin (Japan and the Japanese), “A disturbance in Europe means a perfect opportunity to expand our capabilities in Asia.”[6] The Thirty-Fourth Diet (4-9 September, 1914) unanimously approved a war budget, including monies for ten new destroyers for the navy. And by 1915, parliament approved the two-division Army expansion that had originally sparked the Taishō Political Crisis. Continuing hostilities enabled kingmaker Yamagata Aritomo, moreover, to appoint one of his protégés, former governor general of Korea, Army General Terauchi Masatake (1852-1919), prime minister to head another non-party cabinet between October 1916 and September 1918.

Unexpected Consequences↑

The Rise of Katō Takaaki↑

If Japan’s wars against China and Russia had validated the grand nation-building enterprise of the 19th century and provided an immediate boost to the power of the genrō, they had also invited unintended consequences. Despite the rousing patriotic fervor ignited by both wars, political evolution continued apace. Imperial Japan welcomed its first party politician as prime minister in 1898, three years after the engagement with China. And the volatility of parliamentary debate following the Russo-Japanese War drove General Prince Katsura Tarō to form a party of his own, the Rikken Dōshikai (Constitutional Society of Friends) in 1913. It was, nonetheless, Katsura’s third cabinet (December 1912 to February 1913) that was toppled in the Taishō Political Crisis by a coalition of the two principal parties in the Imperial Diet, the Seiyūkai and the Party of National Subjects (Kokumintō).

Likewise, despite the familiar rallying around the flag in August 1914, immediate political developments did not at all meet the optimistic initial expectations of the elder statesmen. While the genrō had, with the premiership of their associate Ōkuma in April 1914 attempted to diffuse the power of the Seiyūkai Party, granting the foreign ministry portfolio to Dōshikai president Katō Takaaki (1860-1926) complicated the agenda from the start. Indeed, twenty-two years Ōkuma’s junior, with a strong personal quarrel with the elder statesmen and a powerful conviction in the importance of civilian cabinet responsibility in policy making,[7] Katō immediately demonstrated that he would not be distracted by established protocol from pursuing his own agenda. The outbreak of war in Europe, in particular, offered an ideal opportunity for the foreign minister to seize control of the policy-making process.

Under the Meiji Constitution of 1889, all executive, legislative and judicial powers - including the power to declare war - resided in the Japanese emperor. In reality, a decision for battle was made through consultation among some combination of imperial advisers: the genrō, cabinet, military leaders and/or the Privy Council.[8] While the elder statesmen had been intimately involved in both wartime decision-making and military command during the Sino- and Russo-Japanese Wars, Foreign Minister Katō in August 1914 followed only the minimal constitutional requirement to obtain a cabinet decision and formal sanction of the emperor. At an extraordinary meeting on the evening of 7 August, he persuaded the Ōkuma cabinet to join the war against Germany. The following morning, Katō obtained the emperor’s sanction at the monarch’s summer escape in Nikko, north of Tokyo. The foreign minister approached the elder statesmen only after this cabinet decision and imperial sanction, in a genrō - cabinet conference on the evening of 8 August, in what amounted essentially to a fait-accompli.[9]

Given the great expectations generated in Japan by the outbreak of war in Europe, Katō’s decision for war brought widespread applause. As an anonymous writer declared in the popular monthly, Central Review (Chūō kōron), “We are truly on the road to victory. This is a sense of honor that our people have not felt since the founding of our empire.”[10] In light of such strong public support, Katō’s early August coup marked the start of an unprecedented shift of power from the elder statesmen to the civilian cabinet. Although the shift lasted only as long as Katō retained the foreign ministry portfolio through August 1915, it was a remarkable early glimpse at the most powerful long-term political consequences of the Great War in Japan. Following Japan’s November 1914 conquest of the German fortress at Qingdao, China, the Twelfth General Election in March 1915 catapulted Katō’s party (Dōshikai) to front-runner status in the Imperial Diet (from ninety-five to 150 seats) and decimated the majority party since 1900, the Seiyūkai (from 202 to 104 seats). From January, moreover, Katō commanded the most important foreign policy concern following the Qingdao victory — the question of Japanese rights in China. Given the enormous public expectations for the opportunity of war, the fall of Qingdao had spurred widespread calls in Tokyo for an immediate consolidation of Japanese continental interests. Widely known as the “Twenty-one Demands,” the series of treaties concluded with China in June 1915 marked the most comprehensive set of rights negotiated with China in the wave of rights acquired by the great powers after the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). To the Japanese public, they were, as described by Tokyo University Professor Yoshino Sakuzō (1878-1933), the “bare minimum” necessary.[11] As such, they marked another major political coup for Katō and the Foreign Ministry.

Party Politics for Imperial Japan↑

Katō would resign from the Foreign Ministry portfolio just two months after the Sino-Japanese Treaties to forge a path to a cabinet of his own. And although his principal domestic political rival, elder statesman Yamagata Aritomo, blocked Katō’s ambition for several years, the foreign minister’s decisive control of the foreign policy agenda in the first year of the war was a harbinger of more profound political changes to come. Those changes engulfed Japan following the two-year reign of Army General Terauchi Masatake (October 1916 to September 1918), and the most serious consequences of wartime inflation, the Rice Riots.

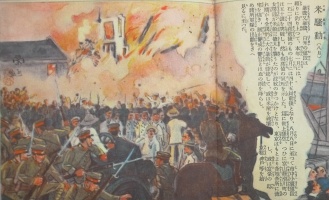

Discontent over the skyrocketing price of rice brought fishermen’s wives in Toyama prefecture to the streets at the end of July 1918 in what would ultimately become a nation-wide series of riots, strikes, looting incidents and armed clashes involving 2 million participants. Calm was restored by mid-September, but only after a declaration of martial law and mobilization of 100,000 troops.[12] More importantly, the turmoil ended the two-year premiership of Yamagata protégé, General Terauchi Masatake, and forced Yamagata to do the unthinkable. Although the elder statesman had originally championed the Ōkuma cabinet in April 1914 as the best way to deal a deathblow to the majority party in the Diet, the Seiyūkai, by September 1918, he agreed to a government headed by Seiyūkai Party president Hara Takashi to bring calm to Japanese streets.

The advent of the Hara cabinet marked a new era of party politics in Imperial Japan. Although he hailed from an upper-level samurai household and thus outranked most of the lower-level samurai among Japan’s elder statesmen, Hara was the first prime minister in Japanese history to hold a seat in the Lower House of the Imperial Diet.[13] His administration was, moreover, the first to be staffed by a majority of party members. The Hara cabinet, most importantly, set the stage for a decade of political reforms in Japan that rivaled the original nation-building enterprise of the latter-19th century. It promoted a massive expansion in secondary and higher education, doubled the number of eligible voters to 3 million men and faithfully participated in the Washington Naval Conference. Upon this foundation, interwar Japan would move decisively from an era of unbridled imperial and military expansion and oligarchic rule into a new 20th-century inclination for internationalism and democratic reform.[14] As the principal champion of democracy in Japan, Tokyo University Professor Yoshino Sakuzō, declared in January 1919, “The new trend of the world is, in domestic policy, the perfection of democracy. In foreign policy, it is the establishment of international egalitarianism.”[15]

Conclusion↑

Far from consolidating oligarchic authority as originally anticipated by elder statesman Inoue Kaoru in 1914, the Great War, like the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry (1794-1858) in Japan over half a century earlier, thrust Japan onto an entirely new political and diplomatic trajectory. While Tokyo had eagerly adopted the trappings of empire and oligarchic authority in its 19th-century enterprise of nation building, the economic transformation of Japan during the First World War and global shift after 1919 toward structures of peace placed Japan squarely on the path of internationalism and democratic reform. Following the advent of Japan’s first true party cabinet in 1918, universal male suffrage arrived in 1925 and laid the foundation for a transfer of power as decisive as the mid-19thcentury shift from feudal dynasty to constitutional monarchy — this time, from oligarchy to political party cabinets. The first string of party cabinets in Japanese history from 1924 to 1932 mobilized the power of the newly expanded electorate to promote new multi-national organizations such as the League of Nations, International Labor Organization and International Court of Justice; disarmament conferences at Geneva (1927) and London (1930); and the rights of women, labor and rural tenants at home. The September 1931 Manchurian Incident and fourteen subsequent years of war in Asia and the Pacific would severely slow the momentum for democratic reform in Japan. But that momentum would return in full force following the military defeat of Japan’s forces of reaction in 1945.

Frederick R. Dickinson, University of Pennsylvania

Section Editors: Akeo Okada; Shin’ichi Yamamuro

Notes

- ↑ Martin Gilbert’s 615-page “complete history” of the First World War devotes sixteen pages to Japan. Gilbert, Martin: The First World War. Second Edition: A Complete History, New York 2004.

- ↑ For brief coverage of this scramble, see, Dickinson, Frederick R.: Japan, in: Hamilton, Richard F. and Herwig, Holger (eds.): The Origins of World War I. Cambridge 2003, p. 302.

- ↑ For a convenient overview of this political history, see Sims, Richard: Japanese Political History since the Meiji Renovation 1868 – 2000, New York 2000.

- ↑ Queen’s Hall Speech, 19 September 1914. Cited in Ferro, Marc: The Great War, 1914-1918, London 1973, pp. 20-1.

- ↑ Inoue Kaoru kō denki hensankai: Segai Inoue kō den [Biography of the Late Lord Inoue], volume 5. Tokyo 1968, p. 367.

- ↑ Nakano, Seigō: Taisenran to kokumin no kakugo [The Great War and the Peoples’ Preparedness]. Nihon oyobi Nihonjin [15 September 1914], p. 24.

- ↑ Katō’s personal quarrel with the genrō derived from his origins in the Owari feudal domain, headed by a branch of the Tokugawa family, which the elder statesmen’s predecessors in the Satsuma and Chōshū domains had vanquished in the political transition of 1868. Katō’s insistence on civilian cabinet responsibility in policy-making derived from twelve years of residence and observation in London, first as an apprentice for Mitsubishi Enterprises, then as Japanese ambassador to Britain. See Dickinson, Frederick R.: War and National Reinvention. Japan in the Great War, 1914-1919, Cambridge, MA 1999, pp. 36-40.

- ↑ Originally established in 1888 to deliberate on the draft constitution, the Japanese Privy Council consisted of a chairman, vice chairman and ultimately twenty-four councilors appointed for life to serve as an advisory body to the emperor. For a brief overview of war powers in Imperial Japan, see Takeuchi, Tatsuji: War and Diplomacy in the Japanese Empire, Garden City 1935, pp. 452-453.

- ↑ For in-depth coverage of these maneuvers, see, Dickinson, Japan 2003, pp. 306-9.

- ↑ Kuro Zukin [pen name]: Kono toki [At this Time]. Chūō kōron [Fall 1914], p. 32. The article was originally written on 15 August.

- ↑ Yoshino Sakuzō: Nisshi kōshō ron [On the Sino-Japanese Negotiations]. Tokyo 1915, pp. 255-6.

- ↑ Lewis, Michael: Rioters and Citizens. Mass Protest in Imperial Japan, Berkeley 1990.

- ↑ Mitani Taichirō: Nihon seitō seiji no keisei [Formation of Japanese Party Politics]. Tokyo 1967. In English, see Duus, Peter: Party Rivalry and Political Change in Taishō Japan. Cambridge, MA 1968.

- ↑ For more on this, see Dickinson, Frederick R.: World War I and the Triumph of a New Japan, 1919 – 1930. Cambridge 2013.

- ↑ Yoshino Sakuzō: Sekai no dai shuchō to sono junnōsaku oyobi taiōsaku [Great World Trends and Policies of Adaptation and Response]. In: Chūō kōron, volume 34 no. 1 (January 1919), p. 143.

Selected Bibliography

- Burkman, Thomas W.: Japan and the League of Nations. Empire and world order, 1914-1938, Honolulu 2008: University of Hawaii Press.

- Dickinson, Frederick R.: War and national reinvention. Japan in the Great War, 1914-1919, Cambridge 1999: Harvard University Press.

- Dickinson, Frederick R.: World War I and the triumph of a new Japan, 1919-1930, Cambridge; New York 2013: Cambridge University Press.

- Dickinson, Frederick R.: Japan, in: Hamilton, Richard F. / Herwig, Holger H. (eds.): The origins of World War I, New York 2003: Cambridge University Press, pp. 330-336.

- Duus, Peter: Party rivalry and political change in Taishō Japan, Cambridge 1968: Harvard University Press.

- Inoue, Toshikazu: Dai ichiji sekai taisen to Nihon (World War I and Japan), Tokyo 2014: Kōdansha.

- Murai, Ryōta: Seitō naikakusei no seiritsu (The establishment of the party cabinet system, 1918-1927), Tokyo 2005: Yūhikaku.

- Takeuchi, Tatsuji: War and diplomacy in the Japanese empire, Garden City 1935: Doubleday, Doran.

- Yamamuro, Shin’ichi: Fukugō sensō to sōryokusen no dansō. Nihon ni totte no Daiichiji Sekai Taisen (Faultline between complex and total war. World War I from the perspective of Japan), Kyoto 2011: Jinbun shoin.