Advance of Russian Forces in East Prussia↑

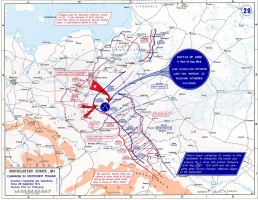

In the first months of the war, the German army’s tactical operations proceeded according to the Schlieffen Plan, with the main strike being directed first against France. The Russian Empire’s geographical expanse meant a lengthy period of mobilization, which, in the German General Staff’s opinion, would enable them to hold eastern Germany with only one army until a victorious conclusion of the war in the West had been achieved. Contrary to pre-war predictions, two Russian armies, under pressure from their Western allies, had already advanced into East Prussia in the middle of July, and on 19 July General Paul von Rennenkampf’s (1854-1918) 1st Russian (Nemanskaia) Army had inflicted defeat upon the enemy at the Battle of Gumbinnen. The victory was not strategically important, and the Russian occupation of East Prussia produced a massive flow of refugees and popularization of the concept of the "Eastern March" suffering the "atrocities of the Russian Cossacks."[1]

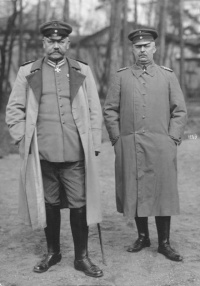

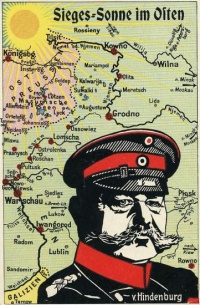

The threat of losing its Prussian stronghold forced the German Staff to adjust their original plans and redeploy two divisions on the Eastern Front. The retired general Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934), the embodiment of the Prussian military tradition, was named as the new commander of the 8th German Army. General Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937) was appointed Chief of Staff.

The Defeat of General Samsonov’s Army↑

The new German plan of operations proposed swift actions against General Aleksandr Samsonov’s (1859-1914) 2nd Russian (Narevskaia) Army, which was cut off from Rennenkampf’s units by the Masurian lakes. The events that played out 26-30 August 1914 around Allenstein were a complex mixture of luck and accident, the uncoordinated actions of the Russian front and military commands, and the military endurance and heroism of individual units. As a result the German 8th army managed to surround Samsonov’s divisions, who outnumbered them, and the general himself, realising the hopelessness of his position, ended his life by committing suicide. In the end, the Russian side lost around 120,000 men, of whom 95,000 were taken prisoner, as well as the entire army’s equipment.

The Mythologising of the Battle of Allenstein↑

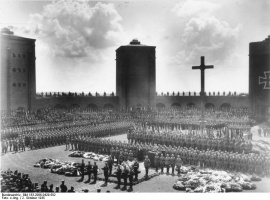

From a strategic point of view, the battle, which was to become known as the Battle of Tannenberg, was not a key event on the Eastern Front during WWI, neither leading to the final defeat of the Russian Empire, nor even to an end to the Russian occupation of East Prussia. Rennenkampf’s forces were only expelled from the province in the autumn of 1914, and in the winter of 1914/15 a second brief incursion ensued. Nevertheless, it is difficult to overestimate the symbolic and political significance of this battle. The very name "Battle of Tannenberg" indicated the German interpretation of it as revenge for the defeat of the Teutonic Knights at the hands of the united Slavic and Lithuanian forces in 1410 (known to the Russians as The Battle of Grunwald). The very idea of the "Second Cannes" of the Eastern Front was the origin of one of the more significant German national myths of the WWI period, the Weimar Republic and the early Third Reich.

For the Russians, the defeat of the Narevskaia Army was a heavy blow to morale.[2] The "infection of the Russian colossus by the Tannenberg bacillus"[3] led to the Russians’ loss of faith in their own power and the likelihood of eventual victory. Representatives of the military elite, thanks to the work of a specialist investigative committee, assessed the reasons for defeat very realistically. Nonetheless, even before the 1917 Revolution, society began to form its own impressions, foremost among these being the perception that it was Russia’s sacrifice to save Paris, and the story of Rennenkampf’s "treachery", which fitted in neatly with the idea of a German conspiracy. After the Revolution, the reinterpretation of this negative military experience was mainly undertaken by different social and professional groups of the Soviet and Emigrant military elites.

Oksana Segeevna Nagornaja, South Urals Institute of Management and Economics

Section Editors: Yulia Khmelevskaya; Katja Bruisch; Olga Nikonova

Translator: Trevor Goronwy

Notes

- ↑ Jahn, Peter: "Zarendreck, Barbarendreck". Die russische Besetzung Ostpreußens 1914 in der deutschen Öffentlichkeit, in: Eimermacher K. a.a. (ed.): Verführungen der Gewalt. Russen und Deutsche im Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg, Munich 2005, pp. 223-242.

- ↑ For detail on the reworking of the Russian experience on the Eastern Front during the war in Soviet Russia and the emigration see: Nagornaja, Oxana: "Syndrom Tannenbergu". Rosyjska instrumentalizacja wschodniopruskiego doświadczenia, tlum. Iwona A. Ndiaye i Ewa Romanowska ["The Tannenberg Syndrome". The Russian Instrumentalization of the Eastern Prussian experience. Translated by Ndiaye i Ewa Romanowska], in: Borussia. Kultura -Historia - Literatura, 41 (2007), pp. 202-216.

- ↑ Noskoff, A.: Mit der russischen Dampfwalze, Berlin 1939, p. 91.

Selected Bibliography

- Jahn, Peter: 'Zarendreck, Barbarendreck'. Die russische Besetzung Ostpreußens 1914 in der deutschen Öffentlichkeit, in: Eimermacher, Karl (ed.): Verführungen der Gewalt. Russen und Deutsche im Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg, Paderborn 2005: Fink, pp. 223-242.

- Nagornaja, Oxana Sergeevna, Ndiaye, Iwona Anna; Romanowska, Ewa (eds.): 'Syndrom Tannenbergu'. Rosyjska instrumentalizacja wschodniopruskiego doświadczenia doświadczenia ('Syndrome Tannenberg'. Russian instrumentalisation of the East Prussian experience), in: Borussia. Kultura - Historia - Literatura 41, 2007, pp. 202-216.

- Showalter, Dennis: Tannenberg. Clash of empires, Dulles 2004: Potomac Books Inc..

- Tietz, Jürgen: Das Tannenberg-Nationaldenkmal. Architektur, Geschichte, Kontext, Berlin 1999: Bauwesen.